Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

23 May, 2020

I’ve been on a bit of a Truesound Transfers trip these past few days. You know, that small Berlin based company run by Christian Zwarg that restores old recordings in such a way that they sound as if someone had only captured these voices yesterday – and not in 1901! While I was visiting the TT website to check if some of their older albums are still available, I came across a lot of new stuff that immediately caught my attention. For starters: a 1919 cast album of La Fille de Madame Angot in English with the forces of The Beecham Light Opera Company, conducted by Eugene Goossens Jr., 16 glorious tracks plus 11 bonus tracks that include French versions from 1903 onwards. And I might as well mention the Betty Fischer album, too, with recordings from 1912-1953. Yes, the Betty Fischer who created the role of Gräfin Mariza in 1924. But the thing that was actually the biggest surprise for me, personally, was the discovery of Josef Josephi (1852-1920).

A formal portrait of Josef Josephi from 1899. (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

The name of Josef Josephi was familiar to me because he’s always mentioned in articles about Fritzi Massary’s early days at the Metropoltheater, where she was part of the notorious “Jahresrevuen.” Those were a tourist attraction and must-see for affluent locals in the early 20th century when Richard Schultz took over the directorship in Behrenstraße (today’s Komische Oper). Mr. Schultz turned this luxurious new theater into a high class amusement temple: you could sit and dine (as you can today at Tipi am Kanzleramt), you could smoke everywhere including the auditorium, and you could meet the prostitutes from nearby Friedrichstraße in a designated cruising area, they were let in for 1 Mark one hour after the beginning of the performance and gathered in the middle of the balcony.

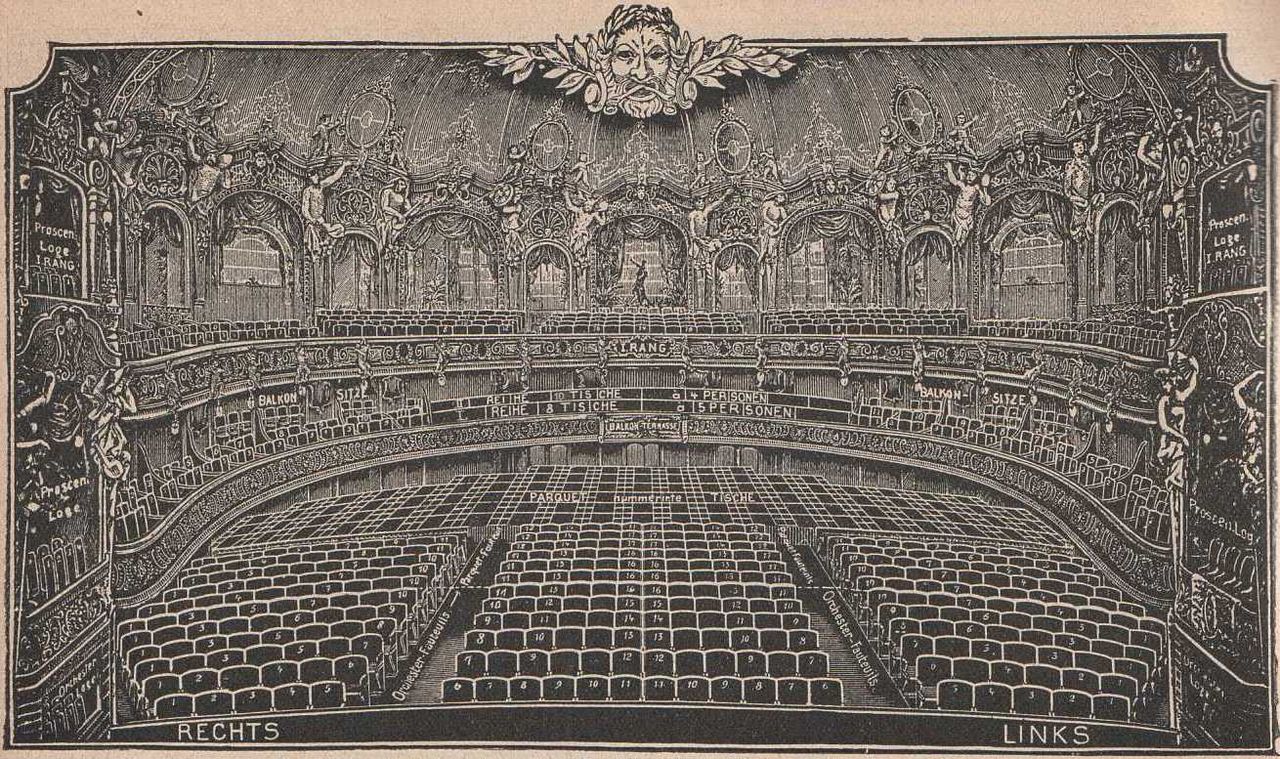

Looking at the seating of Metropoltheater in Berlin in 1912. The back of the stalls was reserved for tables, the middle of the grand tier had a section without chairs for “the ladies” to stand and look – or be looked at.

On stage, Mr. Schultz offered girls, girls, girls. With as little costuming as possible. And sketches about things that had happened during the previous year. He offered breathtaking sets and four top stars: Fritzi Massary as the “grand cocotte” was one of them, Josef Josephi as the “bonvivant” was the other, then there was the celebrated comedian Guido Thielscher and the devilish snob Josef Giampietro. They were all lured to the Metropol with staggering salaries. Miss Massary received 24.000 Mark a year, Giampietro 35.000 Mark, and Thielscher 40.000 Mark. You can read about it all in Otto Schneidereit’s Berlin, wie es weint und lacht: Spaziergänge durch Berlins Operettengeschichte. Sadly, Schneidereit doesn’t mention the salary Mr. Josephi received, but one can assume it was in that price range.

Sheet music cover for the Victor Hollaender revue “Das muss man seh’n!”

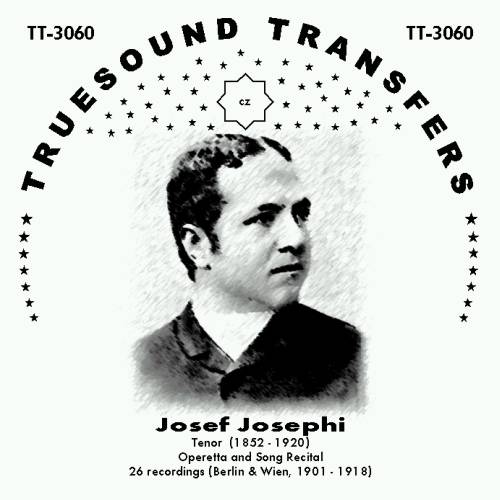

Back to Truesound Transfers. Their Josef Josephi album contains 26 recordings made between 1901 and 1918, i.e. during these fabled Berlin years. Which means, many are from Metropoltheater shows such as Auf in’s Metropol, but also early material such as Berlin bleibt Berlin from which you hear “Das Mädel comme il faut” from 1902.

Mr. Josephi sings with a clear straight forward voice, no “operatics” ever, and he gets the delicious puns of the lyrics across various times over. Because the joke in this particular appraisal of beautiful girls is this: “Ein Mädel comme il faut / mit dem reizendsten … Trikot”. Josephi hesitates saying “Trikot” to allow the listener to insert the more obvious rhyme “Popo”, which means “beautiful ass”. Interestingly, even though the singer repeats the joke over and over again, it never gets tired. Because Mr. Josephi never gets tired himself.

The cover of the Josef Josephi album by Truesound Transfers.

The newspaper Neue Freie Presse remarked about him: “This singing comedian had a very particular physical appearance and was unsurpassed in the sharpness with which he practically carved out the words in songs and couplets.” You can witness this “carving” here, many times over.

At the time these recordings were made, Mr. Josephi was already 50 years old (in 1902). He was obviously a man at the top of his game, and his highly relaxed playing of a bonvivant, the way he dryly delivers jokes that would be unthinkable today in an age of #metoo is a reminder of a “Fach” that has disappeared. He celebrates the joys of life, the positive aspects, the fun of chasing girls like a sport, without turning into a sad sex addict.

Josef Josephi (middle) with his Metropoltheater colleagues Fritzi Massary (right) and Josef Giampietro (back) in 1906. (Photo: Julius Freund)

In the recordings that follow on the TT album Mr. Josephi gets older and older, but his style stays the same, the voice remaining fresh and full of character. He reminded me of Maurice Chevalier in Gigi, minus the famous French accent. Instead, you get a hint of a Viennese accent. And actually some Viennese songs, too, such as “Lass dir Zeit” from Carl Zeller’s Der Kellermeister. The Viennese shading is somewhat amusing because most of the songs are appraisals of Berlin and its modernity, urbanity, and sometimes a lament about the many changes that have destroyed “our beloved old Berlin”.

While listening to these tracks and realizing how old Mr. Josephi was at the time of recording, I wondered where he had been before he became a star attraction at the Metropol in revues written by Victor Hollaender. And now comes the big surprise, at least it was a big surprise to me.

This singing comedian with the unique physical appearance and sharp way of carving out words had a major career in Vienna before he was hired by Richard Schultz. And not just some career, but actually singing the Viennese world premieres of various Johann Strauss and Millöcker operettas, among them Der Bettelstudent (Jan Janicki next to Girardi’s Symon), Zigeunerbaron (Count Homonay), Paul Aubier in Der Opernball, the Duke of Urbino in the Vienna premiere of Eine Nacht in Venedig. The list goes on endlessly, if you find Mr. Josephi in Kurt Gänzl’s Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre where he’s listed as Josef Joseffy. His real name was Josef Ichhäuser, which translates – when spoken causally – as “I am hoarse”. He was an actor before he turned to singing, and his acting abilities shine through, always.

Josepf Josephi in “Bettelstudent,” and operetta he created together with Alexander Girardi. (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

It’s not surprising that the Neue Freie Presse calls Mr. Josephi (their spelling) a member of the “Elitekorps der Wiener Operette” in their obituary. They mention the strong competition that existed between Mr. Josephi and Mr. Girardi, both of them superstars by the 1890s. I wonder if Mr. Josephi might have taken the Berlin offer to get away from Alexander Girardi, a bit like Renata Tebaldi transferring to the Metropolitan Opera because Maria Callas ruled supreme at La Scala in the 1950s. Sometimes a diva needs space for herself. And the same is true for divos.

Josef Josephi as Prince Antarsid in Suppé’s “Die Afrikareise.” (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

Hearing the Berlin recordings – which include the Millöcker number “Liebe fordert Studium” (“Love demands some studying”) and two bits from Zeller’s Kellermeister, as well as a song from the Dreimäderlhaus follow-up Hannerl, with music adapted by Lafite – you realize that that’s one of the central voices of what is often labeled “classic” Viennese operetta of the 19th century. Josephi was a famous Adam in Vogelhändler, he sang Eisenstein etc. with a voice that squeezed out top notes, but that floats along in the most suave and smiling way. With such textual clarity that you can write down every word he sings, from beginning to end, without sacrificing the so called “line” or “melodic arch”. It really is a miracle to hear this!

The Victor Hollaender song “Die Nacht von Berlin” from a Metropoltheater “Jahresrevue.” The song “Der Flieger” is part of the Truesound Transfers “Josef Josephi” album.

But the biggest miracle is that the Truesound Transfer restorations make him sound so fresh that I can hardly believe these recordings come from the stone age of operetta-of-record. Especially the earliest recordings, in which Mr. Josephi is accompanied by piano, do not show their age. That changes a little after track 9 when a small orchestra comes in, because the sound of that band is a bit “off”. But you quickly get used to the background rumble since the voice remains in perfect focus.

As time goes on and Mr. Josephi gets older there are a few more sentimental songs like “Der alte Taler” (1912) or “Könnt’ man noch einmal so jung sein” from the aforementioned Hannerl (1918). But Christian Zwarg has edited the album in such a way that after this short dip into melancholia we finish with the rousing “Der Flieger” (1911) in which Mr. Josephi takes a young lady on a plane ride – and imitates the noise of the engines. It’s a snappy number by Victor Hollaender, delivered with seductive energy and suggestive charm.

A view of Berlin today, very different to the times when Josef Josephi sang about the fun one could have near Alexanderplatz in songs such as Victor Hollaender’s “Du mein altes Berlin.” (Photo: Christian Lue / Unsplash)

A short word about the songs themselves: many others are by Victor Hollaender as well who is almost forgotten today, overshadowed by the fame of his son Friedrich. These pre-WW1 gems by Hollaender Senior really deserve a revival, with carved out words, and the obvious joy Mr. Josephi brings to them.

The legendary “Tralalala” song by Victor Hollaender, made famous by Fritzi Massary.

A few years ago Christian Zwarg released compilations of entire “Jahresrevuen”, such as Auf in’s Metropol (1905) and Das muss man seh’n! (1907), both with scores by Victor Hollaender. On these albums you hear Mr. Josephi, too, but you hear him alternating with cheeky Fritzi Massary and extra snobbish Guido Giampietro. Which makes it even more fun. The young Miss Massary truly is marvelous, e.g. singing the famous “Tralalalala”. And she gets to whistle in a “Pfeiff-Duett” which was also recorded by Josephi with Fritzi Schenke. Comparing both versions is a joy. Sadly, these older albums are not in the TT back catalogue anymore. But if you already have them, dig them up again.

And if you don’t know Josef Josephi yet, his solo album is in the “currently available” section of Truesound Transfers. It’s a master class in operetta singing and worth listening to even if it’s just for the hilarious way Mr. Josephi rolls his “rrrrrr” at times to send couplets into overdrive.

Josepf Josephi in 1901 as seen in the magazine “Berliner Leben.” (Photo: E. Höffert)

By the way, as late as 1917 Mr. Josephi played Ollendorf in Bettelstudent, and he created the role of Father Benedikt in Künneke’s Das Dorf ohne Glocke at Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater in 1919. He died on 8 January, 1920, in Berlin.

But as a member of the “Elitekorps der Wiener Operette” he is buried in Vienna on the cemetery in Hietzing. Might be worth looking him up the next time you’re there!

The Fritzi Massary ‘Kalman’ CD is also well worth a listen. TT transfers are superb: most ‘pre-electric’ (i e pre 1925) recordings are very difficult to listen to with pleasure because one has to make so many allowances for the primitive recording, but TT rise above this, and voices especially sound realistic and ‘live’. Strongly recommended!