Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

29 March, 2020

You could be surprised: here’s a brand new Willi Kollo (1904-1988) biography, and the only picture you’ll find anywhere in or on it is the cover showing a key-moment from the musical Catch Me If You Can. Is this some sort of joke by author Wolfgang Jansen? What does that show have to do with Willi Kollo? Is he a Frank Abagnale Doppelgänger, an operetta con-artist who fooled everyone?

The cover for Wolfgang Jansen’s Wlilli Kollo biography. (Photo: Waxmann Verlag)

This idea sums up Mr. Jansen’s biographical goal pretty neatly. Because in these 390+ pages he’s trying to “catch” the real Mr. Kollo in the midst of many controversial political activities, which have been covered up by his children, who in turn tried to stop the publication of this book for decades. Instead, they wished that their positive and romantic “narrative” should be the one for the ages.

In 2008 daughter Marguerite edited her father’s memoires as „Als ich jung war in Berlin…“ Literarisch-musikalische Erinnerungen. Already back then, any reader who paid close attention stumbled over some contradicting tales of “resistance” to the Nazi regime on the one hand and “cooperation” on the other. I recall vividly asking Miss Kollo about these contradictions back then, and being told that I’m hallucinating and have it all wrong. I’ve been waiting for Mr. Jansen’s book to come out ever since so that someone would explain this schizophrenia to me.

Willi Kollo’s “Als ich jung war in Berlin…“ Literarisch-musikalische Erinnerungen,” edited by Marguerite Kollo.

In the new biography there’s a document from the British “Licencing Advice Office.” They tried to evaluate Mr. Kollo’s relationship to the Nazis as part of his “de-nazification” procedure (so he could get a permit to begin work again and start a publishing company). The office came to the conclusion that they couldn’t prove anything compromising, Kollo was “cleared.” But there’s a June 1948 remark saying: “Kollo is also on the whole what may be termed ‘fishy’.”

Of course such fishiness informs almost everyone and everything in the entertainment world of those years, because everyone had things to cover up. German post-WW2 society was one of total silence. Only the 1968 student revolution cracked open this silence and started a process of examination of “our” Nazi past. Starting with a simple black-and-white concept (you were either one of the “good” ones or a “baddie”) this examination has become more nuanced. And current mass market products such as the ARD series Unsere wunderbaren Jahre (“Our Wonderful Years”) about a German industrial family in 1948/49 show that everyone can be many things at the same time, depending on context and how you look at a situation. There’s a lot of grey area. For a proper evaluation you need to know all the facts and backgrounds, but the survivors of WW2 made sure that the “facts” disappeared. And we are often left with a puzzle that doesn’t fit.

Willi Kollo died in 1988. In 1990, his widow Renate Kollo contacted researcher Wolfgang Jansen to discuss the possibility of a biography. At the time, the works of Willi and his famous father Walter (1878-1940) were not performed regularly anymore, and the idea was that a biography might stir interest – and inspire new productions.

Mr. Jansen began working on the project in 1991, requesting that he should have complete access to the family archive and the support of the family itself. They all agreed that Mr. Jansen would be permitted “to freely write about his research and present the results with a respectable non-fiction publisher.”

Not a complete picture identical with the historic person?

When the manuscript was ready in 1994 the quarrelling began, lawyer’s letters went back and forth, and the manuscript never got published. Mr. Jansen was told that the “complete picture which he painted of their father was not identical with the historic person, as we know it through his works, contemporary context and available documents.” The private Willi Kollo letters were, of course, still under copyright, and they are under copyright until today. The documents by others, in the possession of the Kollo family, were party “official” and free to use. But to separate the one from the other was a huge task.

Mr. Jansen kept the manuscript and material in a drawer for years. Until in 2010 the Universität der Künste (UdK) in Berlin hosted a conference entitled Remigration und unterhaltendes Musiktheater in den 1950er Jahren, i.e. a survey of the entertainment industry in Germany in the 1950s when artists returned from exile and were confronted with a new situation – and with colleagues that had not been forced into exile and had florishing careers in Nazi Germany instead. How were the returning artists treated, how easy or difficult was it for them to get a foot in the industry again, how did networks from Nazi times continue and prevent the formerly “degenerate” artists to pick up their careers again?

Willi Kollo is one of many names worth discussing in this context. Mr. Jansen planed to give a talk on him in Berlin. But a few days before the conference was due to start he received a letter from Marguerite Kollo forbidding the lecture. Mr. Jansen presented this information at the conference – and the various operetta researchers reacted shocked by such a boycot. I remember that well, because I was there, talking about Kalman’s post-war operetta Arizona Lady.

Mr. Jansen’s forbidden conference paper was published in the 2012 book Zwischen den Stühlen. And now, eight years later, he presents the full story with the cleaned-up manuscript that had been in his drawer. After many legal advisers have gone over it to make sure the Kollo family cannot sue and stop the publication, again.

The book “Zwischen den Stühlen: Remigration und unterhaltendes Musiktheater in den 1950er Jahren,” published in 2012.

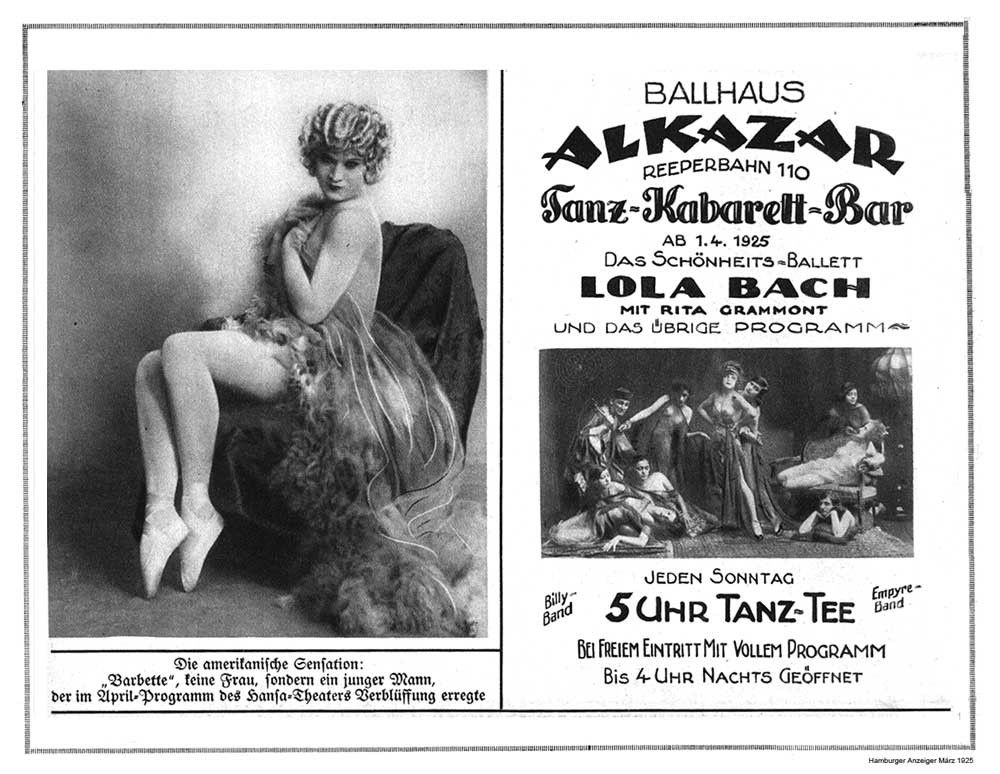

This might explain the noticeably “neutral” presentation and very “general” chapters on the development of the entertainment industry in Germany from the late 19th century onwards. I found these uninteresting because they have nothing new to say. But things get better as soon as Mr. Jansen zooms in on Willi Kollo and starts chronicling his career. Which started when he was 17 and got a chance to write for the “beer cabaret” Weiße Maus where dancers such as Lola Bach presented “scandalous” ballets. There was a lot of nudity, and there was everything the Weimar Republic is famous for in terms of liberation and decadence. And despair in times of hyper-inflation.

Lola Bach was taken to court in 1921 for “offending public decency” with her “beauty ballets.” (Photo: Page from Hamburger Anzeiger, 1925)

Undressing is the new dressing

Mr. Jansen discusses Willi’s complicated relationship with his father who left Willi’s mother to live with soubrette Alice Hechy (1893-1973) for whom he hired one theater after the other so she could star in shows tailor made for her. One of them was called Lady Chic and highlighted – as always – her bodily features. Again with staggering nudity. A reviewer wrote: “undressing is the new dressing.”

Alice Hechy in 1925. (Photo: Alexander Binder)

In the Twenties, Willi Kollo managed to make a name for himself as writer, composer, and performer. He had many successes, but before 1933 he remained in the shadow of his more famous peers. That changed after 1933, even though he and his father ended up in the Handbuch der Judenfrage, listed as “Jewish.” He managed to get that corrected (as did Ralph Benatzky, by the way). And his career in film, theater, and early TV blossomed.

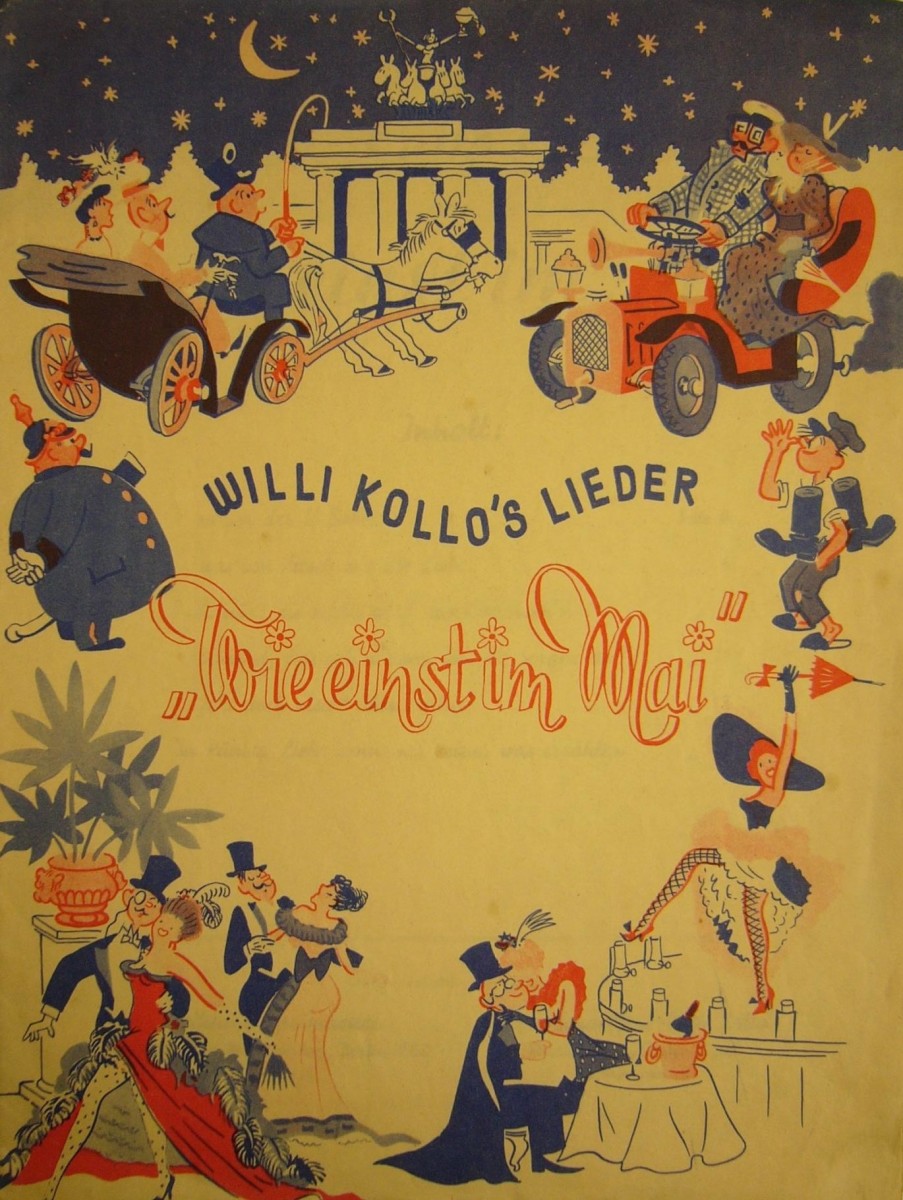

Song selection from Willi Kollo’s 1943 version of “Wie einst im Mai.”

A highlight was the 1943 re-write of Wie einst im Mai, a large prestige production for which Willi added various songs to his father’s popular 1913 score. That’s the version recorded by René Kollo years later for EMI, and it’s also the version the Kollo family insists theaters performe today instead of the original which is copyright free. (Walter Kollo died in 1940.) The publisher is not allowed to hand out that performance material, it seems.

The CD version of “Wie einst im Mai” with René Kollo. (Photo: EMI)

What exactly Kollo Jr. believed in during the years 1933 to 1945 will remain “fishy,” which also applies to Kollo Senior who never received the honors bestowed on Paul Lincke by the Nazis who brought Lincke back as a shining example of “Aryan” Berlin operetta, with Frau Luna as the most famous example.

Dangerous new spirit

In the years after WW2 Willi Kollo proved himself an outspoken “conservative.” And when the student revolution broke loose in 1968 he published a book with comments that condemned the “new spirit” which he saw as “dangerous.”

Mr. Jansen also tells the story of Kollo’s first stage production in Berlin after the war, in 1950, entitled Hellgelbe Handschuhe at Komödie am Kurfürstendamm. Apparently it was a disaster. A reviewer called the melodies “very soupy musical conversation.” Someone else remarked it was “the decline of operetta” (“Niedergang der Operette”) and a “political stupidity” (“politische Dümmelei”). There was booing in the theater, which prompted Kollo – sitting at the piano – to call the police. This caused the even bigger scandal. It also shows how “paranoid” Kollo had become.

It seems he stayed that way.

Kollo vanished from the public eye which, in turn, now focused more and more on his famous son René whose career as a Wagner tenor flourished, but also included a few operetta outings. Marguerite Kollo was her brother’s manager for years and helped get recordings of works by Walter and Willi Kollo onto the market. They give testimony of how she (and presumably her family) wanted “operetta” to sound. I am tempted to repeat the verdict from above: “very soupy musical conversation” instead of the snappy and highly original style you hear on historical Walter Kollo recordings. (Of course this 1980s style is also historic, in its way.)

The 1992 recording of “Drei alte Schachteln” with René Kollo and Hermann Prey. (Photo: Eurodisc)

When the city of Berlin celebrated its 750th birthday in 1987, West-Berlin’s operetta venue Theater des Westens presented the musical Cabaret. While East-Berlin’s Metropoltheater decided to pay attention to the Kollo’s contribution to Berlin operetta, with a program entitled Abends bei Kollos. It premiered on 30 May, 1987, Maria Mallé got to sing a few famous Claire Waldoff songs written by Kollo. Peter Renz was also part of the program, long before he became a favorite at Komische Oper and star of Die Perlen der Cleopatra as well as other Kosky hits.

Claire Waldoff in the Kollo operetta “Drei alte Schachteln.”

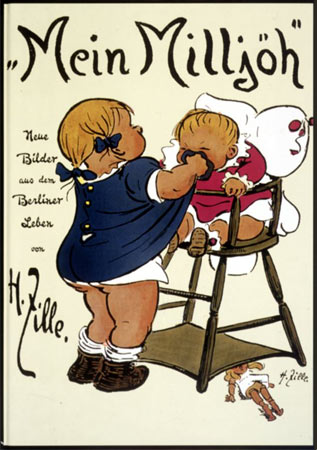

Willi Kollo sat in a box at Metropoltheater and soaked up the applause. It was his last public appearance. He died six months later, on 4 February 1988. In an obituary it says, “Kollo managed to capture the spirit of old Berlin his chansons, and that spirit lives on in them as it does in the drawing of Heinrich Zille.”

Heinrich Zille’s 1913 collection of scenes from Berlin’s working class life, entitled “Mein Milljöh.”

Collage and colleagues

In his biography, Mr. Jansen presents many documents as documents, i.e. not integrated into his text. He also presents various short biographical sketched of others that run parallel to his main narrative. All of this makes the book appear like a collection of source material. It also means that Mr. Jansen doesn’t have to comment on anything, leaving it to the reader to decide what he or she wishes to make of the facts.

You might call the book a collage, with very carefully phrased comments at the end. It’s an important first step in “catching” Willi Kollo. And maybe inspire someone to tackle Walter Kollo’s biography, too. Because as fascinating as Willi’s life is, given the time period and political circumstances, the important operettas that define a typical “Berlin” type of the genre were written by Kollo Senior, together with Paul Lincke (1866-1946), Jean Gilbert (1879-1942), and Victor Hollaender (1866-1940). The biographies of the latter two are also something we’re sadly missing.

Robert Gilbert’s famous father Jean Gilbert, composer of operettas such as “Die keusche Susanne” and “Kinokönigin.” (1913)

Should someone write and publish these, please do so with images. This forgotten operetta world has such a unique look and is visually so striking that a book without any images of actors, theaters, posters, playbills, audiences etc. is a loss. A great loss!