Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

18 December, 2017

Of course there’ve been chamber operettas long before 1933, just think of the glorious small scale pieces written by Mischa Spoliansky (Es liegt in der Luft, 1928) or Ralph Benatzky (Meine Schwester und ich, 1930). But for superstar composer Paul Abráhám, the reigning king of early 1930s operetta, an intimate “Lustspieloperette” in 2 acts is rather surprising after three mega-scale blockbusters in a row: Viktoria und ihr Husar (1930), Blume von Hawaii (1931), and Ball im Savoy (1932). They all had massive scores, extensive dance sequences, huge choruses, cinemascope storytelling, dizzying visual effects, and dizzyingly opulent orchestras. But then came the Nazis, and Abráhám was the first to disappear from German stages, almost overnight. Because his work represented everything the new government was opposed to: the eclectic mix of European and ‘Black’ culture, with lots of ‘Jewish’ sentimentality and schmalz thrown in for special effect. Abráhám left Berlin and continued his career in Budapest and Vienna. The first show written for Vienna was Märchen im Grand Hotel, it premiered in 1934 at the Theater an der Wien, but it was a production of the Josefstadt-Theater. Now, the Komische Oper Berlin has revived this forgotten Abráhám work in a pre-Christmas concert performance, offering a rare chance to hear nearly the entire score that has not been previously available as a recording. This new performance is recorded by Deutschlandfunk Kultur and will be broadcast on December 31.

Sarah Bowden as Marylou in “Märchen im Grand Hotel” at the Komische Oper Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Robert-Recker.de)

The librettists for Märchen im Grand Hotel are Alfred Grünwald and Fritz Löhner-Beda, the same two guys that created the previous German language hits with Abráhám. They, too, were on the black list of the Nazis, they too knew that their work would not be performed by premier German theaters anymore, they too were aware of the necessity to write something that could be performed by smaller scale stages in the Austrian, Czech or Hungarian provinces, possibly also in France and England, where their other shows had been produced. (Ball im Savoy was even given in London’s West End in a translation by Oscar Hammerstein II.)

They recycled a play by Alfred Savoir about a hotel waiter falling in love with a princess. It had been turned into a successful silent movie and in 1934 was released as a talkie with Bing Crosby and Kitty Carlisle as Here Is My Heart.

The 1934 movie poster “Here Is My Heart” starring Bill Crosby and Killy Carlisle.

In the Grünwald/Löhner-Beda version, the romance between the princess and her unlikely suitor is framed by a Hollywood story: Sam Makintosh, the head of “Universal Star Picture Ltd.,” is desperate for a new film script that offers something new and includes “a happy, happy, happy end.” His daughter Marylou (a role created by Rosy Barsony) convinces him to try something novel, i.e. film ‘real life’ with ‘real people.’ She tells her father about an exiled Spanish princess living in a grand hotel in Cannes, France. According to Marylou, that face of the princess was made for the movies. (The role of the princess was created by real-life movie star Liane Haid.) To negotiate the contracts and check out if there are any juicy stories going on behind the scenes, Marylou is dispatched to the South of France. And there, disguised as a chamber maid, she becomes a first-hand witness of the romance between waiter Albert (a role written for another movie star, Oskar Karlweis of Drei von der Tankstelle fame) and the exiled royal who is surrounded by her stiff-upper-lip entourage; it includes an Austrian prince as a potential fiancé.

Grünwald had used a similar Hollywood frame for Die Herzogin von Chicago in 1928, composed by Emmerich Kálmán and also premiered at the Theater an der Wien, albeit with massive forces and decidedly not in chamber operetta format. The Hollywood theme would again be used, to excellent effect, in 1935 with Benatzky’s Axel an der Himmelstür, which also premiered at the Theater an der Wien and was originally also conceived for Liane Haid, though re-written for Zarah Leander and first presented with her as the temperamental movie goddess.

Zaral Leander together mit Max Hansen, in the original production of “Axel.”

Musically speaking, both Herzogin and Axel are the more effective works. The snappy songs for Märchen im Grand Hotel – such as “Jedes kleine Mädel will glücklich sein” or “Ich geh’ so gern spazieren” – all posess the typical Abráhám vitality, but they don’t quite stand out enough on their own to leave a lasting impression.

Given the personal and professional drama Abráhám had to endure in 1933/34 it’s more than understandable that the score sounds distracted at times, not fully focused. But the premiere, directed by Otto Preminger of later Hollywood fame of his own, was a success. With such a superstar cast, how could it not be? Performers such as Karlweis and Barsony knew how to deliver Abráhám songs with maximum effect, they knew how to balance sentimentality and irony in an ideal way. And they were interesting stage personalities, which is definitely also true for Liane Haid. Imagine three movie stars of today in an operetta like this – let’s say Tom Holland or Ryan Gosling, Zendaya, and Catherine Zeta-Jones – and you can roughly guess what the 1934 effect was.

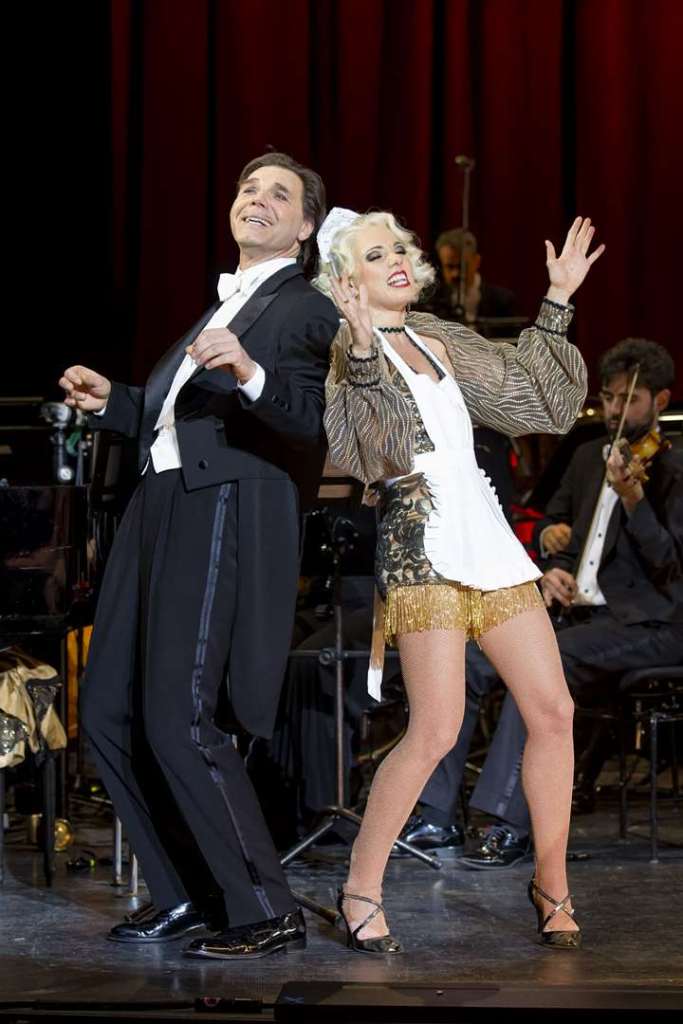

Max Hopp as Albert and Sarah Bowden in “Märchen im Grand Hotel” at Komische Oper Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Robert-Recker.de)

The Komische Oper offers an interesting cast that shifts the focus of the story. As Albert, there is Max Hopp. He narrates the story in a dry comical way and slips into the action when necessary. In contrast to Oskar Karlweis, famous for his somewhat daffy behavior, Hopp is completely self-assured and never, for a moment, the ‘Kleiner Mann was nun’ type that your heart reaches out to. It’s an interesting alternative interpretation that works well, it’s like an intellectual deconstruction of the story or, rather, a detached artificial comment on the action. Max Hopp sings like this, too. No melting tenor tones for the seductive tango “Die schönste Rose,” instead a no-nonsense rendition with a characteristic chanson voice. It’s very effective, because Hopp displays great presence and thankfully stears clear of all ‘operatics’ that can make operetta performances so painful and embarrassing.

As the heroine, Infantin Isabella, there’s soprano Talya Lieberman from the company’s opera studio, singing a wonderfully introspective “Märchen im Grand Hotel” title song that makes time stand still for a moment – because it’s almost a meditation on loneliness, exile, love, life. It’s possibly the most fascinating number in the score, even if it’s not one of the ‘big’ Abráhám tunes.

Strangely, though Max Hopp and Talya Lieberman are both great on their own, they display little chemistry between them. Maybe that’s asking too much of a concert performance, but without that chemistry – and without the hint of romance unfolding – the central plot element of this operetta is absent. Which becomes all the more evident with an Albert who storms forward and takes possession of the world, instead of being shy and charmingly afraid to confess his feelings to Isabella.

The other star role is Marylou, of course. The Komische Oper offers Sarah Bowden who is highly effective as a song-and-dance phenomenon in golden outfits. Her big tap dancing number – brilliantly executed – brings the house down. And all her other numbers are equally well choreographed (presumably by Miss Bowden herself). She sings with a clear, aggressive Broadway voice that is ideal for the part, and she reminds the audience that such a triple treat (dancing, singing, acting) was once the core requirement for any real jazz operetta soubrette. Because of the concert version and the cut dialogue, the latter scenes of Marylou disguised as a chamber maid and wooing Prince Andreas Stephan are shifted to the background. Although she does deliver a raunchy chamber maid number that could be moved straight into Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. It is a master class in how to sing operetta with contemporary panache, bridging the 1934 style with 2017!

Talya Liebermann as Princess Isabella and Tom Erik Lie as Chamoix in “Märchen im Grand Hotel” at Komische Oper Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Robert-Recker.de)

As the Austrian prince, young Johannes Dunz didn’t get many opportunities to show off his wonderful voice. But when he did sing, it was a pleasure to hear his ringing tenor. In contrast to Hopp/Lieberman, he developed noticeable chemistry with Sarah Bowden, and he even dared to join her for a dance routine that would have probably knocked most regular opera tenors off their socks. But not Mr. Dunz! (Bravo.)

Special mention must go to Tom Erik Lie. He took it upon himself to play Countess Inez Pepita de Ramirez, Isabella’s lady in waiting. (In the original version there are more Spanish characters, here they were reduced to one.) In drag, Lie delivered a glorious history of the royal pearl necklace, milking every nuance of the lyrics and singing in an effortless falsetto. Lie returned as President Chamoix, the rich owner of the grand hotel, singing a touching duet about friendship and love with Lieberman/Isabella: “Mon ami.”

In these slow numbers, the magic of the conducting was especially noticeable. And if I’ve waited till last to mention the true star of the evening, it’s because I wanted to save my rapturous praise for the end. Adam Benzwi has returned to the Komische Oper as a conductor, and he demonstrates once more that his way of handling the reconstructed scores of Henning Hagedorn and Matthias Grimminger is beyond special. Too often, conductors simply take these scores and play them as printed. (Which never happened in Abráhám’s times, and which Anton Paulik certainly didn’t do in 1934.) Benzwi reduces the instrumentation, and plays with the various orchestra groups, placing them effectively around his central piano playing. As a result, the title song, which is a mere three pages in the printed piano score, unfolds like a multi-layered waltz of haunting beauty – accompanied by Benzwi at the piano, with a solo cello and contra bass, then solo strings. It’s magical, and it needs a magician like Benzwi to realize that there is such potential in this number and then make it happen. You need great imagination, and passion, to work in such a way with an orchestral score. And Benzwi has come quite a way since he first started with Abráhám in Ball im Savoy in 2013 and fine tuned his skills with two Oscar Straus scores, which he treated with equal liberty and love.

Benzwi is equally at home with the syncopated dance numbers, and you can tell this whole project was supervised by him when you notice how detailed all the singers articulate the Grünwald/Beda lyrics. And: how free and easy they move around in their songs, always sure that Benzwi will follow every breath they take. As Barrie Kosky said afterwards at the first night party: “Adam Benzwi is the René Jacobs of operetta!” (I wouldn’t put it quite like this, but the gist of it is absolutely correct.)

All of this doesn’t make Märchen im Grand Hotel a masterpiece. But it does allow us, today, to take a look at a crucial turning point in operetta history and see what happened in those unchartered post-1933 years when Abráhám was banned from the big German stages, and people such as Nico Dostal took over with Abráhámesque shows like Clivia. (Recently also seen at the Komische Oper, in a full staging.)

It’s a blessing that this performance was recorded, and that most of the music is included in this abridged concert version. Let’s hope that the recording will be released, as a download or CD, so that a serious discussion of operetta in Nazi times can incorporate such long neglected and unheard of titles. (The tricky – but crucial – part of the “8 Lancashire Lads” that accompany the entire score in close harmony was executed by the Lindenquintett Berlin with some help from Philipp Meierhöfer, who doubled as Makintosh.)

Vidina Popov, Catherine Stoyan, Mehmet Yılmaz, Jonas Dassler, Alexander Darkow, Johann Jürgens in

“Alles Schwindel” at Gorki Theater, Berlin. (Photo: Ute Langkafel)

By the way, on the same night that the 1934 Märchen im Grand Hotel was revived in concert form at the Komische Oper Berlin, the Gorki Theater 500 meters up the road premiered the 1931 Spoliansky operetta Alles Schwindel. An equally unknown piece, but here given a new full staging with a dazzling young and juicy tenor lead: Jonas Dassler. Having seen him the night before Märchen im Grand Hotel in a preview, I couldn’t help but wonder how Märchen would have worked with a high strung and sexy performer such as Dassler in the role of Albert. There certainly would have been a very different chemistry on stage. And though, in the end, I truly loved Max Hopp’s performance and admired his enormous acting skills, I am also glad that Berlin is now getting more options in this field. And that we can start thinking in so many alternatives. That is a blessing.

Jonas Dassler and Vidina Popov as Tonio and Evelyne in “Alles Schwindel” at Gorki Theater, Berlin. (Photo: Ute Langkafel)

The man who started it all and made this possible, not just in Berlin, is Barrie Kosky. (No, I am not going into another rhapsodic appraisal now, don’t worry; even if it would be befitting.) Mr. Kosky announced, at the after show party, that this Märchen im Grand Hotel is the first of five Abráhám operettas the Komische Oper will present in five years. Whether they shall all be concert versions remains to be seen… what we can certainly look forward to is Dschainah, das Mädchen aus dem Tanzhaus (1935) and Roxy und ihr Wunderteam (1937), the other two German langue operettas premiered in Vienna before Abráhám had to escape to Paris, Cuba, and New York in 1938 after the “Anschluss” of Austria. Which leaves one more title to guess…. maybe Die Blume von Hawaii, as the most successful operetta of the Weimar Republic?

It would be a fitting finale to the Kosky era which ends in 2022, just like it was the fitting swansong to Weimar.

For more information and performance dates, click here.

Thanks for this very useful introduction to the piece, Kevin. Looking forward to 30 December.

I can’t wait for the broadcast on 12/31. When will Mr. Kosky be sharing Adam Benzwi’s talents in Los Angeles? I’m not sure what the vehicle might but it would be exciting to see what they could do here. Sarah Bowden could return with them! Thanks for the deeply insightful review!