Thomas Krebs

Operetta Research Center

19 June, 2020

In 2018 the score of Hans May’s operetta Die tanzende Stadt (The Dancing City, 1934) came up for sale in London: the printed vocal score with text, published by Editions Charles Brull in Paris, contains numerous handwritten notes plus additional musical numbers, and an English translation. The orchestral score is entirely in manuscript form. The music of a German language operetta by an Austrian composer, written and published in France, first performed in Switzerland, ends up in England – that’s a story not untypical for the 1930s in Europe.

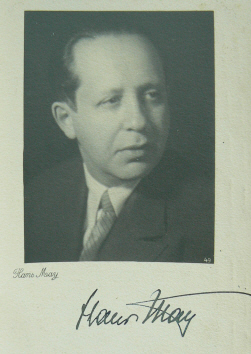

Composer Hans May in 1931, as seen in a German magazine. (Photo: Thomas Krebs Archive)

Hans May, composer of Schlager, revues and operettas as well as music for silent and sound films on the Continent and later in Britain, was born in Vienna, into a Jewish family, as Hans Mayer in 1886.

His younger brother, Karl Michael, born in 1893, also became a composer of songs and film music – in fact, sometimes the two brothers collaborated on films, and it is not always clear who wrote what.

Not much is known about Hans’s early musical training, except that he studied piano with Anton Door and apparently played his first concert as a child prodigy at the Bösendorfer Saal in Vienna when he was 12. Door later sent him to Richard Heuberger to study composition.

Composer Richard Heuberger in 1894. (Photo: Auguste Wimmer)

He started out as a composer of piano pieces and songs and, according to information provided by himself his first composition was published by Bosworth in Vienna, when he was still at school, already under the pen name Hans May.

He became successful before World War I, not only as a composer, but also as the musical director of the Carl-Theater in Vienna. But it was at the famous Ronacher Theatre that his first operetta Der Teufelswalzer (The Devil’s Waltz) was premiered in a lavish production in 1912.

When he was drafted into the army, he wrote a number of patriotic songs, such as Hindenburg, der Russenschreck (Hindenburg, the terror of the Russians).

Paul von Hindenburg in full military uniform, 1915. (Photo: Nicola Perscheid)

After the war he moved to Berlin and was soon busy as a composer of popular songs and music for shows and revues, he also worked as musical director in various cabaret theatres. In 1923 he co-founded the artistic and political cabaret Die Gondel (The Gondola), which made a good name for itself at the height of the Twenties when competition in the entertainment business was fierce.

A signed postcard showing composer Hans May. (Photo: Gregory Harlip)

His thorough musical training and the ease with which he wrote memorable tunes enabled him to explore new fields, and so he began composing for silent films. In 1925 he wrote the score for a feature-length German production of Ein Sommernachtstraum (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), directed by Hans Neumann.

A scene from the 1925 movie “Ein Sommernachtstraum” starring Werner Krauss, Valeska Gert and Alexander Granach. (Photo: Neumann-Filmproduktion)

He also wrote mood pieces that were used by cinema orchestras to accompany silent films, both for the Italian-born composer Giuseppe Becce and his “Kinothek” and in two of his own anthologies. By 1927, he had written at least forty scores for silent films, and with the arrival of the talkies, he became busier than ever, writing score after score.

Among his most popular songs written for films were those performed by the famous tenor Joseph Schmidt, who, due to his diminutive stature, could not have a stage career, but was extremely popular in concerts, and especially on the radio and in movies. The most famous of these was My Song Goes Round The World, sung by Schmidt in the film of the same name.

The film premiere in Berlin in May 1933 was a huge event, but as Jews, May and Schmidt and also the lyricist, Ernst Neubach, had to get out of Germany immediately.

May had already received several threatening and blackmailing letters, and when he left Berlin for Paris, he was forced to abandon his fully furnished nine-room apartment – which was ransacked soon after, his car was stolen and large amounts of his printed music were burned publicly.

The shock at the treatment by the Nazis and their supporters and the stresses of the escape caused May to contract nervous asthma, making him unable to work for several months. His wife, Olga, suffered from a depression caused by these experiences. Finding himself unable to establish a foothold in Paris and later in Amsterdam, May opted for England in February 1934.

At first, he was not allowed to work there, though, and when he was finally given a work permit, it proved difficult to find employment in the film industry. Slowly, he began to build a new life, but for a long time he depended on financial support from his daughter Ida Putty, who was also living in London.

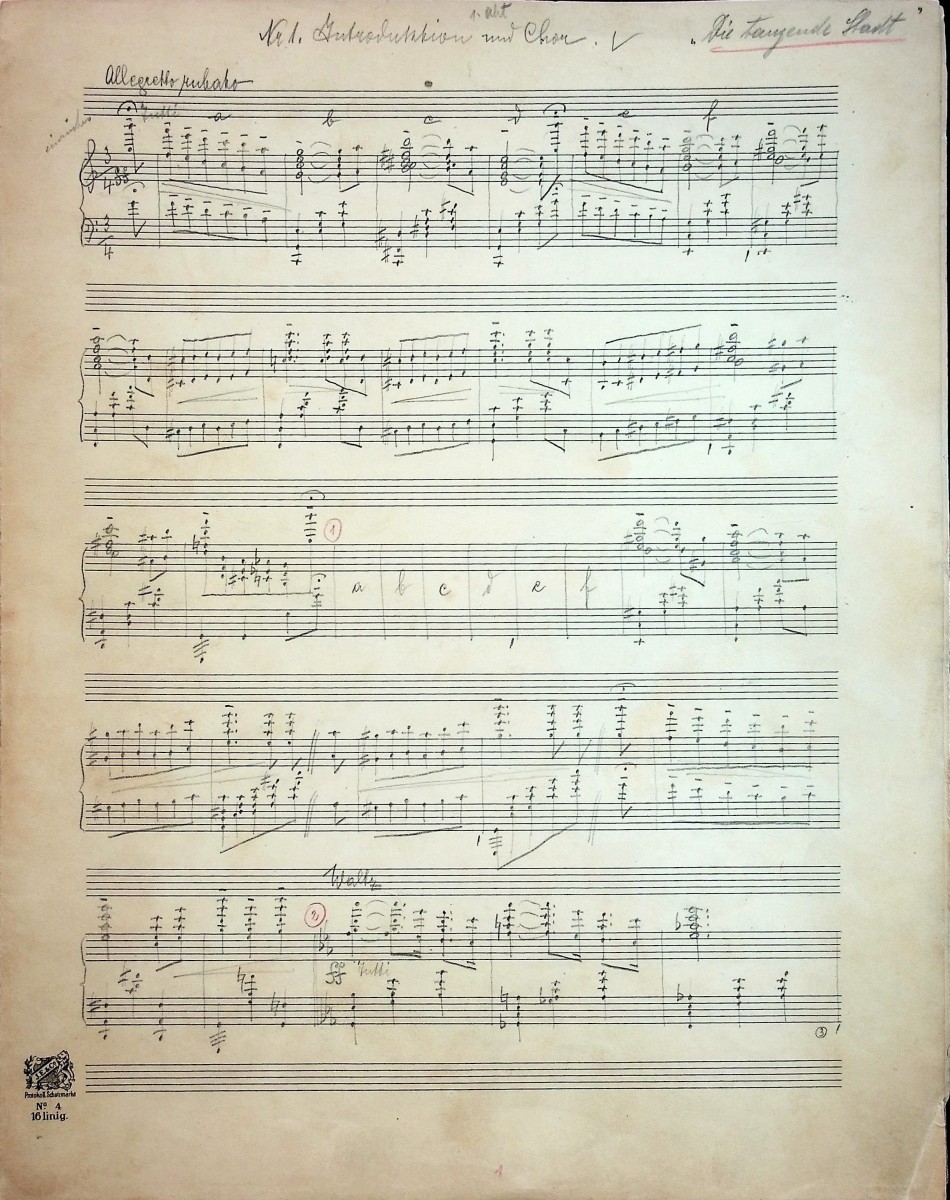

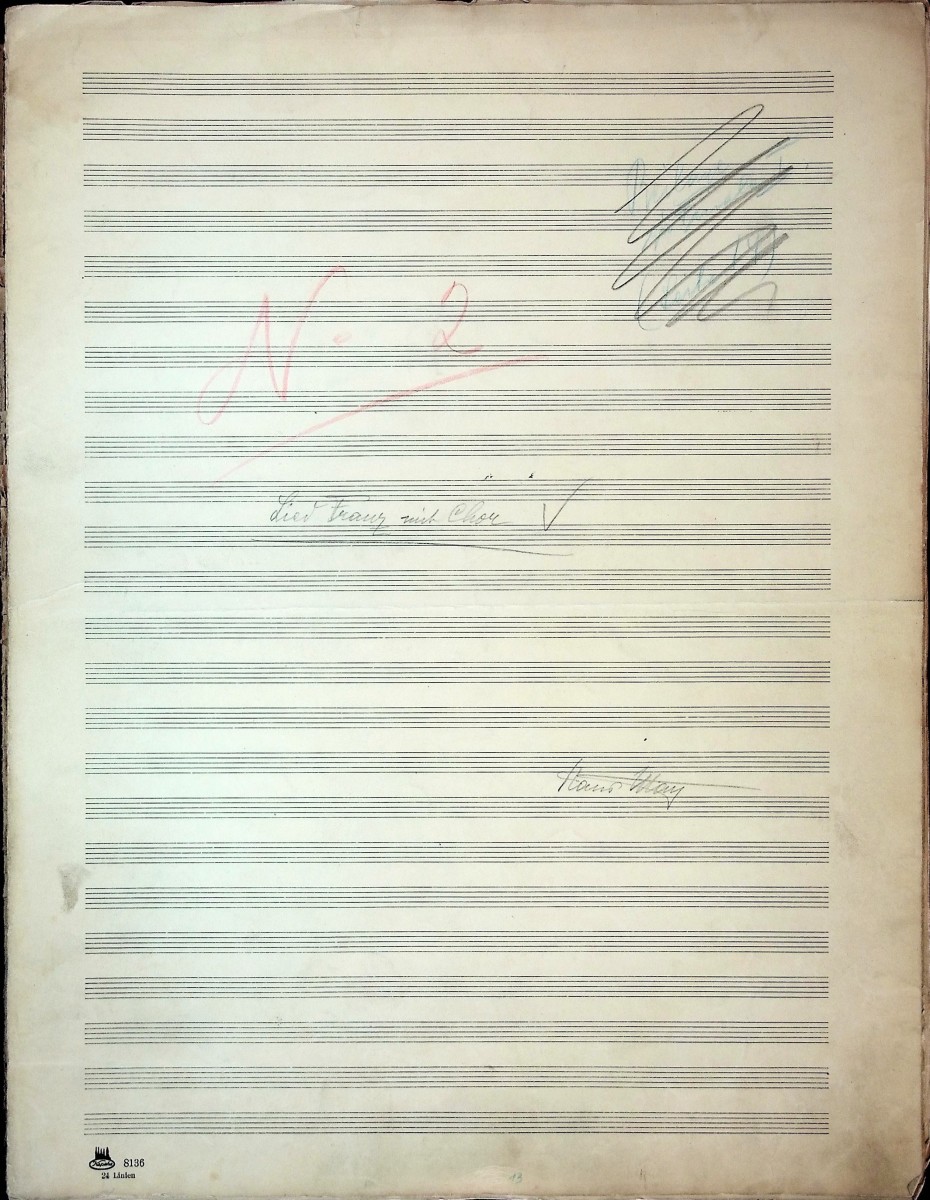

A page from the orchestral material of “Die tanzende Stadt.” (Photo: Thomas Krebs Archive)

The Dancing City was to be given its premiere in London, but instead the first performance was in Zürich, on 29 September 1934 in the original German, with the composer himself conducting. The book was by Carl Rößler and Arthur Rebner. Rößler had been a successful actor and playwright (mostly comedies) for over thirty years. He was 70 when he wrote Dancing City, his first operetta.

In an article in the Viennese newspaper Der Tag entitled “From Shakespeare to Myself”, Rößler stated his belief that the future of the theater lay in operetta and singspiel. The plot of Die tanzende Stadt revolves around the entire city of Vienna wanting to dance the waltz despite Archduchess Maria Theresia having banned it.

The reviewer in the Neue Zürcher Nachrichten found that music and text left something to be desired, despite acknowledging the composer’s ability to cater to the tastes of the audience and to create musical effects. It was risky, according to “th.”, to write an historically informed operetta with such a topic, where audience expectations were bound to be extremely high, and thus to move so close to the greatest masters who had put the inexhaustible flow of melodies from Vienna into classical tones before. The production and performance, though, received high praise.

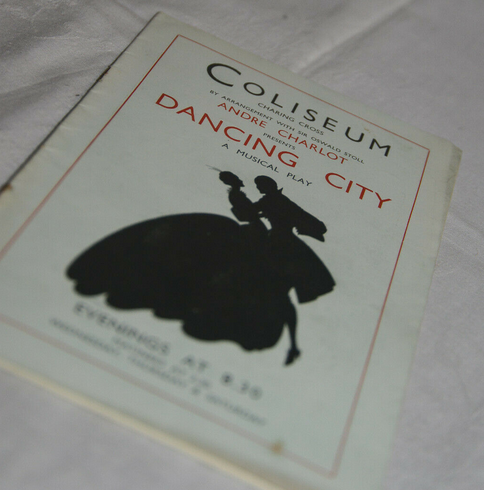

Theater program for the 1935 London production of “The Dancing City” as offered on eBay. (Photo: eBay)

The London premiere at the Coliseum followed on 26 April 1935, produced by André Charlot, with two foreign artists in the leading roles, Lea Seidl and Franco Foresta. The latter apparently had problems with the English language and following complaints he was soon replaced by Derek Oldham. Dancing City ran for 65 performances and closed on 15 June.

Another page from the orchestral material of “Die tanzende Stadt.” (Photo: Thomas Krebs Archive)

The Viennese premiere on 4 October 1935 was at the famous Theater an der Wien, where May had been a very young répétiteur back in 1911 – and had dreamt that one day one of his own works might be performed there. May writes about this in a short article for Neues Wiener Journal, he goes on to say that his operetta was premiered at the London Coliseum and does not mention the Zürich premiere at all.

In fact, two other operettas by him premiered at the Stadttheater Zürich: Traum einer Nacht (Dream of a Night) on 11 May 1935 and König der Zigeuner (King of the Gypsies) on 16 October 1937. Both were great successes with theater goers but somewhat less warmly received by the critics, who, while acknowledging that May, with his experience composing for films, was very skilled, found him unoriginal and too ready to write for the tastes of the general public.

In London, together with another Jewish refugee, the German music publisher Richard Schauer, May established the firm of Schauer & May, publishers of light music, in 1939.

In the spring of 1940 May was interned by the British as an enemy alien and spent two of the four months before he was released on 27 August in the internment camp hospital, due to his poor health.

Finally, more work started to come in and he found employment both as a musical director and as a composer for a number of films, especially in the 1940s: Thunder Rock (1942) and Brighton Rock (1947) are two of the best known examples.

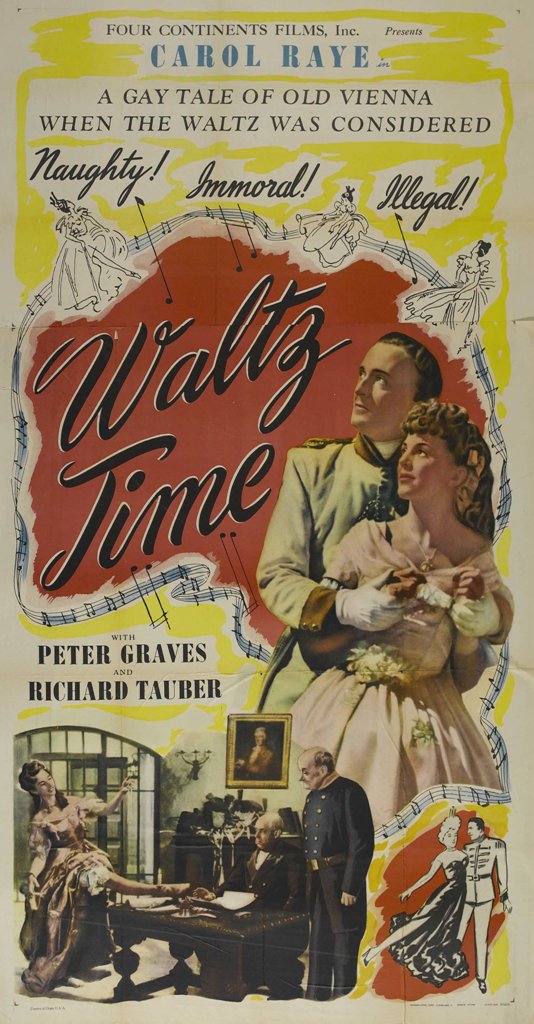

At heart, Hans May always remained a representative of old Vienna, and after Word War II he once again composed waltzes and sometimes quite schmaltzy music for another 20+ films. For Waltz Time (1945), starring Richard Tauber, Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth, he did not only compose the music, but also conducted the orchestra and even had a brief appearance as a Gypsy Troubadour. The plot is the same as that of Die tanzende Stadt.

Poster for the movie “Waltz Time” starring Richard Tauber. It promises a story from Old Vienna and from a time when the waltz was considered “naughty, immoral, and illegal.”

Two very successful London stage productions with music by May were Carissima (1948), book and lyrics by Eric Maschwitz, which ran for 488 performances and was broadcast in a 1959 BBC TV production with Ginger Rogers, no less, and Wedding in Paris (1954), book by Vera Caspary lyrics by Sonny Miller, starring Evelyn Laye and Anton Walbrook (411 performances).

A selection from Wedding in Paris is available on a Sepia CD, coupled with Cole Porter’s Can-Can. A short video clip from the rehearsals has survived with a brief glimpse of the composer at the piano.

A magazine article from “The Sphere” on “Wedding in Paris,” 1954 (Photo: Lylah Clare Archive)

In January 1947 Hans May became a naturalized British citizen. His first wife, who had never recovered from the hardships of their escape from Nazi Germany, died in 1956. In 1957 he married his agent Rita Cave. In December 1958 he went to Beaulieu-sur-Mer in the South of France for health reasons and died there in the early hours of 1 January, 1959.

One of his last appearances had been in a TV program where he recalled the hundreds of hit songs he had written during the silent film days. “They used my music then,” sighs Hans, “to drown the noise of the projector!”

Back in 2018 I bought the material at the Travis & Emery auction, at first I only received the vocal score. I thought it would be better left at the most important music library in the city where the operetta received its first performance, so I donated it to the music division of Zurich’s Central Library.

Meanwhile, a big parcel arrived in front of my door, with the complete orchestral parts. I hope someone will feel inspired to actually perform the show someday, again.

The British films mentioned above, and others for which May provided songs/music, are talked about by Adrian Wright in his new book “Cheer Up” which I am in the process of reading and reviewing for ORCA