Alan Lareau

Operetta Research Center

30 November, 2016

America’s popular music tradition is often referred to as the “Great American Songbook,” a national heritage. A focus on its uniquely “American” character, however, can obscure the diversity and intercultural dynamics of our cultural history. American music reflected the “melting pot” character of an immigrant nation; in Tin Pan Alley, most famously, a motley assortment of ethnic backgrounds gave voice to the modern experience. Another, less known story, however, is that of the touring artists and musical exchanges that maintained a vital connection between the old world and the new in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Theater and music impresarios brought star performers and artists as guests from Europe to showcase the newest transatlantic developments and to keep cherished artistic traditions alive. Some of these guest artists stayed on and established themselves as milestones of their new culture, while others returned to their homelands, often maintaining contacts on both sides of the Atlantic. Though composer Victor Hollaender (1866-1940), one of the latter, is merely a footnote to American music, his visit to Milwaukee in 1890 was doubly foundational, for here he made the first, modest steps of what would become an illustrious career, while in this year he helped to found a new venture that would mark the city’s culture. His ties to the United States continued at least sporadically until his death in this land as a refugee from Nazi Germany. Hollaender’s memoirs, an excerpt of which appears here in translation, tell the story of his Milwaukee career in a lively, anecdotal tone.

Victor Hollaender in Milwaukee, 1890. “Yenowine’s Sunday News,” September 14, 1890. (Collection Alan Lareau)

There was a certain irony in the fact that Hollaender came to the “German Athens,” as Milwaukee was known thanks to its rich immigrant culture, as he hailed from “Athens on the Spree,” the burgeoning capital of the new German empire, Berlin.

The German capital Berlin, Unter den Linden, at the end of the 19th century. ( Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Photochrom Prints Collection)

He was not, however, a Berliner by birth. He descended from a poor Jewish family from Upper Silesia (now Poland); his father, a medical doctor, had moved to Berlin with his thirteen children in 1872. Here, the Hollaender clan – above all the three brothers Victor, Gustav (a composer and director of a conservatory) and Felix (an author and theatrical director) – grew into a tone-setting artistic dynasty. The German journalist Gabriele Tergit wrote, “I think the German Jews are the only community in the world that in three generations rose from impoverished peddlers to the highest intellect.” Showing musical talent from an early age, Victor pursued the “light muse,” writing both words and music for songs and operettas, largely designed for amateur performances in schools and in the home, and began work for the theater as an assistant conductor in Budapest.

When he ventured to America, Victor was but 24 years old and just starting his career.

“Papa” Joseph Kurz had founded Milwaukee’s first professional German theater troupe in 1852, called the Kurz German Stock Company. They first played in Mozart Hall, a wooden building on the current site of the Milwaukee Public Library. The next year they took over the top floor of Market House on Market Square, the present site of City Hall. This 500-seat hall was a stable home to the company for the next fifteen years. The composer Christoph Bach arrived in Milwaukee from Germany in 1855 and became the ensemble’s resident conductor and a leader of the city’s musical scene. In 1868, Henry (Heinrich) Kurz, Joseph’s nephew, who had been a pillar of the ensemble since its founding, built the Stadt Theater on Third Street, between Cedar (now Kilbourne) and West Wells Streets, in the block where the Hyatt Regency Hotel now stands. The Stadt, seating a thousand patrons, grew into one of the great sites of German-American theater. ‘Every classical drama and all modern plays of importance were presented by talented actors,” a history of Germans in America relates. “They performed twice a week—on Wednesdays and on Saturdays—and when guest actors were appearing, they also played on Fridays.” The troupe also exchanged artists with the Berlin Stadttheater as well as with St. Louis and Chicago’s German theaters. In 1884, a trio of Stadt actors – Julius Richard, Ferdinand Welb, and Leon Wachsner – took over joint direction of the theater, which was remodeled in 1886. As joint directors of the United German Theaters of Milwaukee and Chicago, the team also presented their productions in Chicago’s McVicker’s Theatre on a weekly basis.

By now, this troupe was considered the finest German-language stage in the land.

Panorama map of Milwaukee, with a view of the City Hall tower, 1898. (Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division)

In 1871, meanwhile, distillery owner Jacob Nunnemacher opened his Grand Opera House as an English-language performance venue on the site where the Pabst Theater now stands. When the brewer “Captain” Frederick Pabst took over the sponsorship of the “Kurz” troupe by buying the old Stadt Theater in 1889, he initially planned to build a new theater for them, but after some deliberation he instead purchased and totally renovated Nunnemacher’s much larger house. The “Old Stadt” closed with a guest performance of King Lear in German on April 18, 1890, but the trio of Richard, Welb and Wachsner continued their direction in the new house. For the dramatic art in his new hall, however, Pabst harbored considerably more ambitious plans including popular musical theater, and thus the ensemble needed a musical director for this novel brand of entertainment.

Along with a group of guest actors, Victor Hollaender landed in New York on September 6, 1890, to complement the stalwarts of the permanent, Milwaukee-based ensemble. On September 17, 1890, the new venue opened as the “Neues Deutsches Stadt Theater” (New German Municipal Theater), but it was generally just referred to as the “Stadt” and sometimes as the “Pabst.” The remodeled house boasted luxurious and spacious appointments with four foyers, so that a local newspaper promised it would become “what such institutions are, to a great extent, in Europe, not merely a place where one goes to witness a play or opera, but also a place of rendezvous where one meets his friends and has a chat with them.” Its auditorium seating 1,200 people featured over 1,400 electric light bulbs, and electricity had been installed to run the stage technology and ventilation. For the grand opening, the house orchestra delivered Beethoven’s “Egmont” overture, led by the illustrious Christoph Bach, who continued as the house conductor of dramatic and intermezzo music. Before the curtain rose on Goethe’s classic tragedy of Egmont, actress Clara Zahl recited a prologue in which, as the Milwaukee Sentinel reported, she “spoke as a German to Germans and pleaded for the maintenance of all that made the German race recognized as one of the foremost in the world.”

Wisconsin Street, Milwaukee, 1900. (Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division)

Following the memorable opening, the programming of the first season at the New Stadt consisted mostly of German-language plays that have meanwhile been forgotten—a mixture of comedies, melodramas, tragedies, and farces. Of true “classics” one found only Schiller and Shakespeare; alongside the Viennese comedies of Raimund and Nestroy, the season featured contemporary authors such as Ludwig Fulda, Adolph l’Arronge, Paul Heyse, Oscar Blumenthal, and the hugely popular comedy The Sabine Women (Der Raub der Sabinerinnen, known in America as A Night Off, or A Page from Balzac) by Paul and Franz von Schönthan. As a “stock” theater, the Stadt troupe played neither in repertory (with plays alternating on different nights) nor ensuite (with one play being offered for a block of performances) as is customary today, but instead was constantly preparing new pieces that were often presented only once or in some cases twice. Sundays were family days for comedies and farces or musical works. The venture into the new genre of musical theater was hesitant, the repertoire limited to an occasional farce with songs or a one-act operetta. Young newcomer Victor Hollaender quickly made a favorable impression with this popular material. A production of the vaudeville Mamsell Nitouche, with music by Hervé, was occasion for an appreciative review of Hollaender’s spirited and careful musical direction, which gave the piece life despite the limited musical abilities of the cast and poor sets. But throughout the season, Hollaender “had little opportunity to display his full ability,” as the German-language weekly Der Freidenker regretted.

The visitor was adopted into the circles of Milwaukee’s German-American luminaries, such as composers Christoph Bach or Hugo Kaun, and he was a charter member of the artist’s society “Allotria” at its founding in November of 1890. In a February 1891 concert of the Milwaukee Music Society, he premiered two ballets composed for his as yet unproduced operetta Rhampsinit. A full stage production of this operetta in May 1891 was the crowning event of the New Stadt’s first season. The composer had attempted to launch the work in Berlin some years earlier, but the production had fallen prey to intrigues within the troupe and was canceled before it saw the light of day there. In Milwaukee, this comedy of hidden identities and romantic intrigue at the Egyptian court, or an “operatic burlesque,” as it was billed, was enthusiastically received. Although most of the cast was not up to the musical demands of the piece, they compensated with their comic abilities. “The choral pieces are magnificent and daring,” a critic reported, “and in truth, they are much more than operetta music.” The 1890-91 season closed with a repeat performance of the operetta. (In 1893 the work finally premiered in Germany under the title König Rhampsinit, but it never asserted itself in the repertoire there.)

Cover of the piano-vocal score to the operetta “Rhampsinit” (König Rhamsinit), which was first performed in Milwaukee in 1891. (Collection Alan Lareau)

“The artistic success of the past season was significant,” the Freidenker reflected on the close of the first year. “New and old talents proved themselves in fine collaboration, and the repertoire, though not rich in novelties, was carefully selected.“ Happy with his successful, if not overly rewarding, work in Milwaukee, Victor returned to Germany in order to wed his fiancée, and his place as musical director of the Stadt was taken by one G. Kruse.

During the subsequent seasons at the New Stadt, an arsonist plagued the house, and in January 1895, the theater burned out completely due to an electrical fire.

Fire destroys the Neues Deutsches Stadt Theater in 1895. Milwaukee Sentinel, January 16, 1895. (Collection Alan Lareau)

Pabst ordered it immediately rebuilt on the same site, and the Pabst Theater, as the new incarnation was named, still stands as a cultural hub of Milwaukee. But already before the legendary devastation suffered by the German-American cultural heritage in the wake of the First World War, the German-language theater was losing steam. In New York, the great theatrical entrepreneur, Gustav Amberg, lamented that his house was doomed to failure: “What I need is to go to the cemetery and revive all the Germans who are buried there and who used to crowd the Thalia for me. That is what the German theater in New York lacks.” Milwaukee’s German productions in the Pabst faltered through the Twenties but managed to hang on until 1931, when the last curtain finally fell for the German theater company, which was officially dissolved in 1935. Today the Pabst is a cultural hub of modern Milwaukee, but its German heritage is largely forgotten.

Milwaukee’s Pabst Theater today. (Photo: Alan Lareau)

Victor Hollaender soon revisited America in an unusual way: On board the ship to New York in 1890, he had traveled with the Rosenfeld troupe of “Liliputians,” who were embarking on the first of several highly successful American tours. He consequently composed two pieces for them, both which they also brought to Milwaukee. His comic operetta in four acts, The Dwarf’s Wedding at the Court of Peter the Great (with additional music by Emil Christiani) was performed not in Pabst’s Stadt Theater, however, but instead in the Davidson in 1892. When The Fair in Midgettown followed in March 1898, the ambitious ballets in particular earned acclaim as “brilliant and beautiful.” Hollaender’s score, for its part, was judged “very clever, but it is chiefly rehashed and contains much of the popular music of the day,” a critic complained. In fact, the composer was a master of compilation, arrangement, and pastiche – techniques that served the popular musical theater of the day particularly well.

Advertisement for “The Dwarf’s Wedding.” “Milwaukee Sentinel,” 3 April 1892. (Collection Alan Lareau)

Several of Hollaender’s compositions were printed in Milwaukee, often in editions co-produced by German music publishers, such as a collection of “Love Songs in the Character of Different Nations” (1893). In 1895, his very first one-act operetta The Singing Society’s Rehearsal (“Die Gesangsvereinsprobe,” 1882) was performed in a concert by soloists and orchestra with the St. Mary’s Church Choir, for the benefit of St. Mary’s School. Occasionally, one of his pieces surfaced in concerts around the Midwest as well, such as a performance of his “Romance” for violin in a Minneapolis student concert of 1895 or a 1897 rendition of his “Fairy Footsteps” by Denver’s Tuesday Musical Club. His musical plays and operettas surfaced in coming years in the repertoire of German-American theater troupes, as evidenced by the Trostel Script Collection in the Milwaukee Public Library, which includes script and score materials for a number of his shows, as does the Tams Witmark Collection at UW Madison; the Pabst Theater Script Collection, preserved at the Max Kade Institute in Madison, contains the script to one Hollaender show, Honest Work (Ehrliche Arbeit, 1892), but it is unclear whether that piece was actually performed in Milwaukee. Subsequent to the ravages of war, dictatorship, and time, few performance materials for Hollaender’s works have survived in Germany, so these rare archival holdings are special jewels for historian.

Cover of “Love Songs/Liebeslieder.” (Collection Alan Lareau)

On his return to Germany in 1891, Victor Hollaender built on his experience in Milwaukee to launch a career as a theatrical conductor and composer. In the early 1890s, worked as musical director of Berlin’s Wallner Theater, a house for popular farces and musical comedies, but following the devastating death of his first child in infancy, he resolved to start life anew and moved with his wife to London, where he worked as a theatrical conductor and band leader, above all in the grand exhibits of entrepreneur Imre Kiralfy. Hollaender’s wife Rosa also appeared in the staged spectacle production of India that took London by storm in 1895. After the birth of their son, however, the Hollaenders returned to Berlin, and Victor served as deputy director of the Stern Conservatory and continued composing songs and theatrical works.

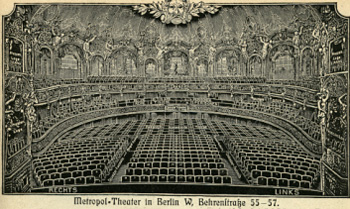

The interior of the old Metropoltheater in Berlin, today housing the Komische Oper.

Victor Hollaender’s breakthrough began in 1902 when he was hired as the house composer and conductor of the Metropol Theater, an elegant entertainment palace featuring opulent musical comedy. Here, together with director Richard Schulz and librettist Julius Freund, Hollaender pioneered the new theatrical form of the annual revue: a colorful show of songs and dramatic sketches that satirized the events of the past year.

These impudent, though never injurious productions were the toast of Berlin society, and their star, Fritzi Massary, became the reigning operetta diva of Berlin. His 1905 hit “Das Schaukellied” made the westward crossing over the Atlantic to serve as the featured number in New York’s Ziegfeld’s Follies of 1910, sung by the theater’s star, Lilian Lorraine. An original cylinder recording can be heard online at the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive.

Sheet music for “Swing Me High, Swing Me Low.” (Collection Alan Lareau)

In 1912, Victor Hollaender returned to America in person with a three-year contract to compose shows for producer Martin Beck’s theaters in Chicago and New York. Just after he arrived in New York, he conducted the American appearance of director Max Reinhardt’s troupe in the musical pantomime Sumurûn, which Hollaender had composed for its Berlin premiere two years earlier. The production was an international sensation, and in New York it was greeted with even more enthusiasm than in its homeland.

Scene from the 1920 film version of “Sumurûn,” directed by Ernst Lubitsch, with a score by Victor Hollaender.

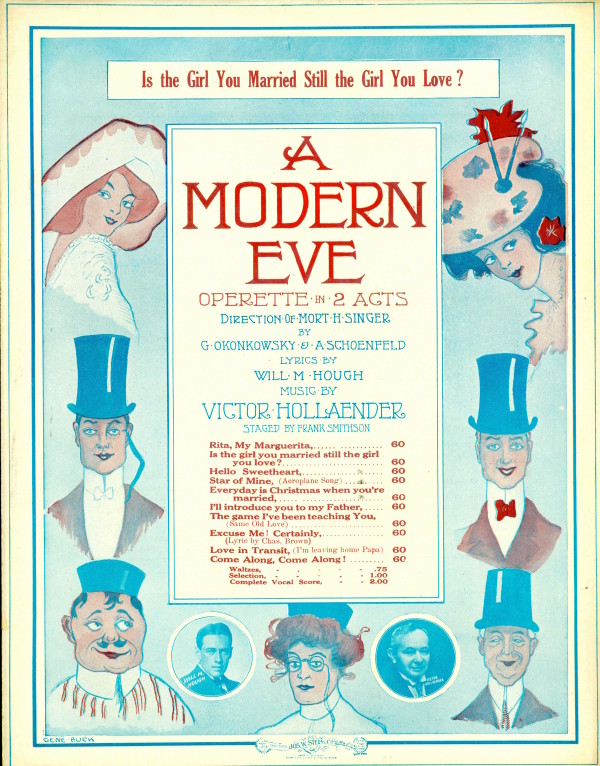

That August, the Milwaukee Journal announced that Victor Hollaender would be returning to town for a visit with local musician Bruno Fink, and recalled the time twenty-two years earlier when he worked at the Pabst. Unfortunately, this second American career was less than satisfactory, for the musical The Charity Girl (with a script by popular humorist Edward Peples) was a flop on Broadway and closed after only 21 performances. Hollaender decided to leave before his contract ended to rejoin his wife and son, who had meanwhile returned to Berlin, and he was safely back home before the Great War erupted. Hollaender’s other show for Beck, a total reworking of Jean Gilbert’s 1910 Berlin operetta A Modern Eve, had been more successful in its Chicago production and toured America for several years, but only made it to Broadway in 1915, long after Victor had left the country, and by that time, much of his music had been replaced with new, American-written tunes.

Sheet Music cover for “A Modern Eve.” (Collection Alan Lareau)

On his return to Berlin, Hollaender told the press that he had enjoyed the best experiences imaginable in America and that he planned to maintain his connections to the country by spending two to three months a year there, even though he could not live there permanently in consideration of his teen-aged son, who was himself embarking on a musical career and insisted on living in Berlin. Hollaender went on to explain the different character of the musical theater in America.

The musical taste of the American audience is quite different from that of the Europeans. People here demand a half-way logical, connected and developed plot, but the Americans only want to hear numbers and hit songs, and they don’t mind a bit if, for example, a scene that plays in beautiful, bright daylight, is utterly darkened for a few minutes and then once again brightly illuminated. That offers variety and makes an impression. The main thing in an American operetta, however, is the refrain. For instance, when a young man confesses his love to a maiden in a hidden place, then twenty couples pop up behind the couple, and the chorus repeats the refrain making the same movements the lead actors made. Then the chorus disappears and the plot continues. To make a tune popular, the director stages five or six different dances for a number. You see, Americans want their musical numbers to be encored five or six times, but they want to see five or six variations.

During the war, Hollaender composed patriotic revues to bolster spirits on the home front, as well as several wholly apolitical musical comedies, and he tried his hand as a theatrical director as well. With military defeat and the end of the monarchy, however, Hollaender found that the era to which he had given voice had suddenly drawn to an end. The Kaiser had fled to Holland, and Germany attempted an admittedly short-lived democracy, the Weimar Republic. American jazz and dance music now set the tone, a fashion for which Victor had little taste or talent. He withdrew from composing and passed the baton to his son, Friedrich, who went on to become Berlin’s finest cabaret and revue composer, writing witty and often bitingly satirical songs.

Friedrich Hollaender (1896-1976) gained his real fame, however, with the advent of a new medium, the sound film. His words and music for The Blue Angel (1930) went around the world, above all in the hit song “Falling in Love Again,” as sung by Marlene Dietrich and later recorded by countless stars from Billie Holiday to Tony Bennett, Linda Ronstadt, and Brian Ferry – and even the Beatles.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Friedrich Hollaender was among the first to flee Germany and to land a job in Hollywood.

There he worked as a film composer for twenty-two years, again writing famous songs for Dietrich (such as “See What the Boys in the Backroom Will Have”). His parents left Germany that same year, settling in London until they could follow their son to California in 1934. Victor Hollaender’s works were purged in Nazi Germany, his music officially banned from the stage, and in the notorious anti-Semitic exhibit of “Degenerate Music” in 1938, his name featured as an example of the pernicious influence of Jews on the German operetta stage. Once the toast of Berlin’s sophisticated entertainment scene, Victor finished out his life in obscurity in his third American sojourn; he was unable to find the slightest work in Hollywood.

In 1940, he was buried in the Jewish section of the cemetery now called Hollywood Forever, and eight years later, his wife was interred next to him.

Victor Hollaender’s grave. (Photo: Robert Wennersten)

Though both had filed papers of intent for naturalization, the citizenship process never came to fruition. Two of Hollaender’s sisters who had stayed behind in Germany were killed in concentration camps, as were countless of his nieces and nephews. Some descendants of those Hollaender lines that had taken the Christian faith in the nineteenth century, meanwhile, had no inkling of their Jewish heritage—a dangerous family secret that only came to light long after the war had ended. Exile, war, and the Holocaust brought a brutal end to the illustrious Hollaender cultural dynasty that had set the tone in Berlin in the early twentieth century.

For a description of Hollaender’s early US career, in his own words, click here.

Victor Hollaender! I have original orchestrations from several of Hollaender’s 1910s U.S. productions (“A Modern Eve,” “Sumurun,” etc) If researchers out there would like scans, please contact me. https://paragonragtime.com/about/collection-of-historic-orchestrations/