Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

26 December, 2016

We admit, in many ways the year 2016 hasn’t exactly been “good news” all around. Yet, from an operetta perspective there have been a few noteworthy new trends that prove that things are changing in a positive way after years (and years) of stagnation. One such change is evident in the new exhibition at the Wien Museum running till the end of January 2017, called Sex in Vienna. Desire. Control. Transgression.

The post for the exhibition “Sex in Wien” at the Wien Museum 2016.

The exhibition was initiated by the new director of the Wien Museum, Matti Bunzl. And what is special about it is not only the effortless inclusion of LGBTIQ* History, with some less familiar aspects of Vienna’s erotic past, for example the story of two cross-dressed men in 1868 who went to various balls to dance and seduce (straight) men. This demonstrates that many of the ball scenes and Heurigen Garten episodes so familiar from operettas could be seen as much more “diverse” than they are usually staged.

The “Wäschermädelball” by Wilhelm Gause, 1898.

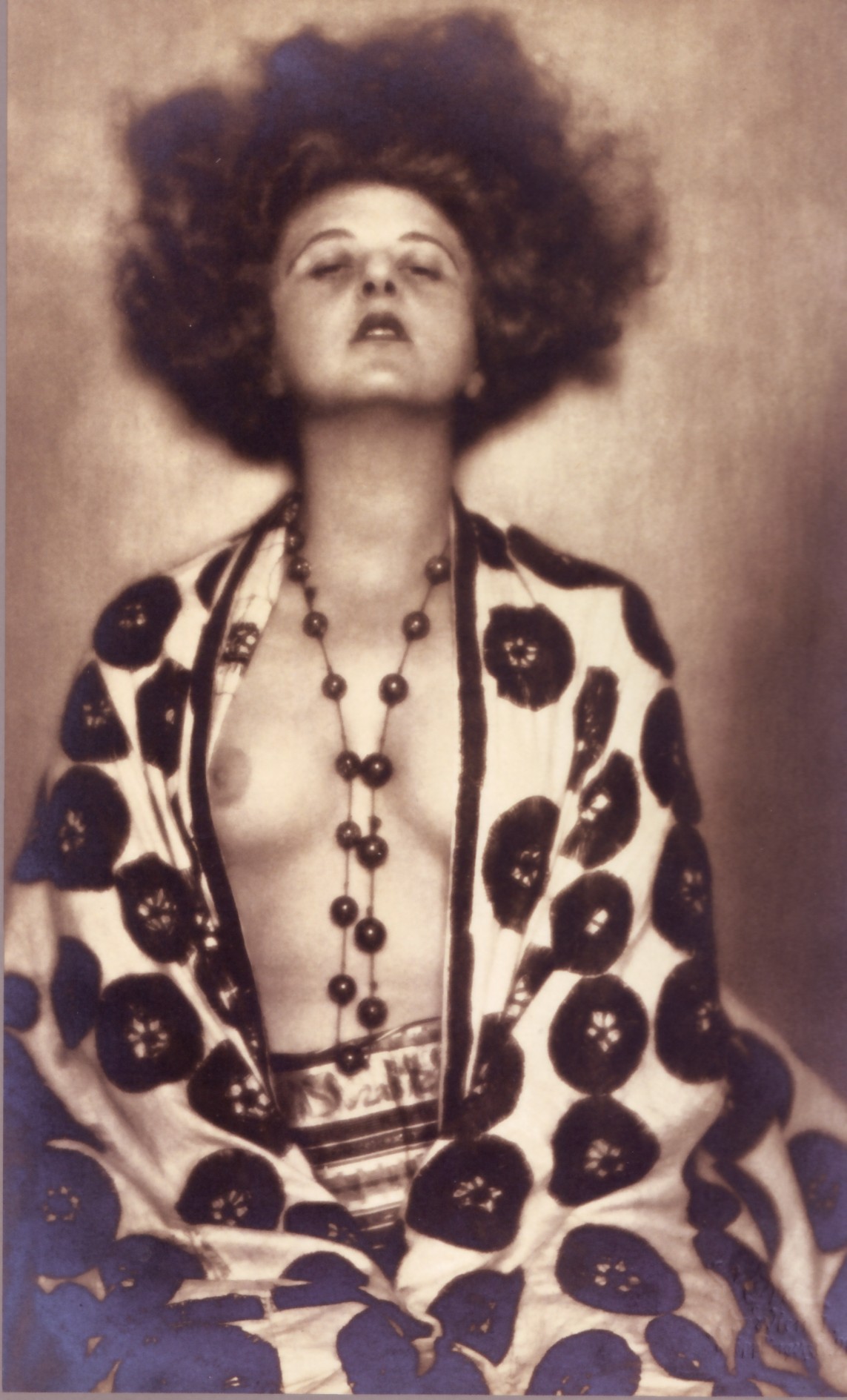

But it’s the equally effortless inclusion of operetta figures in Sex in Wien that stunned us most; an inclusion that is mirrored in the beautiful 18+ catalogue. Right on page 26 you’ll see operetta soubrette Elsie Altmann-Loos in full semi-nude glory, photographed in 1922, shortly before the created the role of Lisa in Kalman’s Gräfin Mariza at the Theater an der Wien. (Which is just opposite from the Wien Museum.) For decades such once all-familiar operetta images were banned from any discussion of the genre, and certainly “sex” wasn’t part of any discussion of operetta in Vienna, or differently put: operetta in general wasn’t part of any discussion of erotic night life in the Austrian capital.

Elsie Altmann photographed by D’Ora 1922.

Later in the catalogue, you’ll find the famous dancer Fanny Elßler, celebrated in the posthumous 1934 Johann Strauss operetta Die Tänzerin Fanny Elßler. An aspect missing in that Bernard Grun/Oscar Stalla show is the fact that Elßler was sexually abused as a child by Count Kaunitz-Rietberg. Her parents received furniture and money in return. The subject of child molestation – also evident in Die Fledermaus with the infamous “ballet rats” in act two – is also not usually represented (or discussed) in operetta literature, let alone performances. Here, the Wien Museum exhibition and catalogue point the way.

Later, there is a stunning photo of Katharina Schratt in 1870 – the era when operetta truly took off in Vienna. She is seen with something like a banana near her lips. The curators and authors of the catalogue inform us, that Schratt was not just the later mistress of Emperor Franz Joseph, but shared him with various other lovers such as Count Wilczek, the King of Bulgaria, and Viktor Kutschera. We also learn that as a younger woman she had “close contacts” with her theater colleague Alexander Girardi – the famous operetta star.

Katharina Schratt in 1870. (Photo: Landesmuseum Niederösterrich, St. Pölten)

And so the saga goes on and on. Including the famous figures familiar from operetta history in a new – yet historic – context. Who would have thought such a thing possible a decade ago? So while we mourn the death of George Michael and so many other pop artists, the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit and all the other political earthquakes of 2016, we are happy about this earthquake in operetta land that’s one of many. And it’s a very welcome one!

If only the unavoidable New Year’s Concert of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra could refresh the image of the Johann Strauss music in a simular way, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel this year. (We know that’s unlikely to happy, but still …)

Postcard “Wien bei Nacht – Porzelanfuhr,” 1900. (Photo: Sammlung Peter Payer)