Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

24 June, 2018

Munich’s recently renovated and re-opened Gärtnerplatz Theater just offered a brand-new staging of The Chocolate Soldier, in the original German language version as Der tapfere Soldat. It’s a production by controversial German stage director Peter Konwitschny, who caused quite a stir (and a legal battle) with his 1999/2000 Csardasfürstin at Semperoper in Dresden. (I must be one of the few people who liked that production, which is as intelligent as his Land des Lächelns at Komische Oper Berlin, long out of repertoire there.) While I hope that the new Munich version will find its way onto DVD – which a more than dazzling looking tenor called Maximilian Mayer as Major Alexius Spiridoff would make worth watching! – there are various CDs of this neglected masterpiece around wand worth considering.

Maximilian Mayer as Major Alexius Spiridoff (left) and Daniel Prohaska as Bumerli in “Der tapfere Soldat” in Munich, 2018. (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

As you might recall, the 1908 premiere of Der tapfere Soldat – loosely based on George Bernard Shaw’s play Arms and the Man – was not a hit. Even thought the Theater an der Wien offered a stand-out cast with Grete Holm as Nadina and comedian Max Pallenberg as Colonel Kasimir Popoff, not to mention Louise Kartousch as Mascha. Pre-WW1 audiences in Austria did not cherish a satire on war and a deconstruction of old-fashioned war heroes. Neither did the Germans, nor the Hungarians. Der tapfere Soldat flopped in all of these countries. Instead, it was the English speaking world that was conquered by the renamed Chocolate Soldier and by the hit waltz song ‘My Hero.’ The original American adaptation was made by Stanislaus Stange and produced on Broadway by Fred C. Whitney. It later transferred to the West End and became a smash British hit, too. Meanwhile, ‘My Hero’ became a fixture of the soprano repertoire, it has been oft recorded. But sadly, only this single number, not the entire show.

The story of a Swiss mercenary called Bumerli, who has joined the Serbian army in the 1880s in their battle against the Bulgarians, chronicles how an anti-hero wins the heart of Nadina one night as he flees from the Bulgarians into Nadina’s bedroom. She is engaged to war-hero Bulgarian Alexius who is out to fight the Serbians. And she is determined to throw Bumerli out of her bedroom and hand him over to authorities, as an enemy and deserter. But matters take a different course when Bumerli explains to Nadina the idiocy of war and of her fiancé, over a box of chocolate munition.

Jasmina Sakr (Mascha), Alexander Franzen (Hauptmann Massakroff), Sophie Mitterhuber (Nadina), Daniel Prohaska (Bumerli), Hans Gröning (Oberst Kasimir Popoff), Maximilian Mayer (Major Alexius Spiridoff) in “Der tapfere Soldat” at Gärtnerplatz Theater, Munich. (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

Nadina and her mother, plus cousin Mascha, all fall for the charming Swiss guy with the chocolate box, they hide him in their house when the Bulgarian patrol comes looking for him. Eventually, this leads to Nadina leaving pompous Alexius, who finds solace in the arms of Mascha. And Bumerli marries Nadina, after she realizes that the men’s world of war craft she so admired is all bullshit. There are some very amusing, and compromising, moments along the way. And there is a lot of sexual innuendo to be enjoyed: about women needing men (“Ohne Männer hat das Leben keinen Sinn”), about women wanting soldiers that are god-like (“ein Leutnant muss kühn wie ein Gott sein”), about a re-evaluation of weak men (“in meinem Leben sah ich nie, ein Schwächling so wie Sie”), and about not believing what society tells you to blindly believe about war and war heroes.

It’s a story that has not lost its topicality in this day and age of aggressive red-button and ‘mother of all bombs’ rhetoric from people such as Trump & Co., and in an age of worldwide refugee streams fleeing from such bombs. Der tapfere Soldat certainly deserves new attention, not just in Munich.

Sophie Mitterhuber (Nadina), Daniel Prohaska (Bumerli) in “Der tapfere Soldat” in Munich. (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

There are two easy-to-access German language recordings: a 1960s radio production from Vienna with Max Schönherr conducting the Großes Wiener Rundfunkorchester, with Fred Liewehr as Bumerli, Erika Forsell-Feichtinger as Nadina, Friedl Loor as Mascha and Fritz Sperlbauer as Alexius. Then, there is the 2012 double disc version on Capriccio, based on a Cologne radio performance conducted by Siegfried Köhler with the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln. It has Caroline Stein as Nadina, Johannes Martin Kränzie as Bumerli, Martina Borst as Mascha, and John Dickie as Alexius. Both can be found on Spotify.

Listening to these two versions shows some interesting developments. While the older recording is technically bland, i.e. you don’t hear details of the orchestration too well, you get a very homogenous cast: everyone back then sang in the same ‘traditional’ operetta style, everyone had slim and flexible voices, everyone comes across as a believable character. In particular Fred Liewehr brings a certain Johannes Heesters charm to Bumerli that was obviously the standard ideal back then. (Heesters himself was too old for such a part in those years, and he never sang it at the height of his career in Nazi Germany, where an anti-war operetta was unthinkable anyway, certainly not one by ‘Jewish’ composer Oscar Straus and by ‘Jewish’ librettists Rudolf Bernauer and Leopold Jacobson.)

M. Ottmann als Mascha in “Der tapfere Soldat”, Theater des Westens, Berlin 1909. (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

What you hear as ‘traditional’ in 1960s Vienna has little to do with how Der tapfere Soldat sounded in 1908 at Theater an der Wien. (Absolutely not classical, more broad comedy in the Vaudeville tradition with Pallenberg leading the way.)

But it was nonetheless a straight forward way of performing the piece with opera people who all knew what they were doing and who had no doubt that their way of doing things was ‘right.’ (It’s a joy to listen to them and their self confidence, especially the ensembles on this recording are glorious.)

The Cologne recording of “Der tapfere Soldat” on Capriccio.

Moving 40 years onwards, to Cologne, the singers are not so secure about stylistic questions anymore. They kind of copy the old ‘traditions’ without reinterpreting them in a unique and convincing new way, and without singing better. The men over-sing and often sound strenuous, while the ladies lack the lightness of Forsell-Feichtinger/Loor. (And the pretty amazing Hilde Rössel-Majdan as mother Aurelia remains unsurpassed anyway.)

On the other hand, you get to hear the orchestra on Capriccio in perfect sound quality, and that’s a treat. And I mean: a real treat! Still, no one buys a Chocolate Soldier for the orchestra, right?

Sophie Mitterhuber (Nadina), Ann-Katrin Naidu (Aurelia), Jasmina Sakr (Mascha), Daniel Prohaska (Bumerli) in “Der tapfere Soldat” in Munich. (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

Both recordings are far superior to recent US-releases, such as the Ohio Light Opera double disc on Newport Classics which uses a new English adaptation by Philip A. Kraus and Gregory Opelka. Considering what a big hit The Chocolate Soldier was in the United States – and considering how many great sopranos have sung ‘My Hero’ – you would have thought that a young generation of aspiring operetta crusaders would have come up with something more than this tired and sexually undercharged version of the show, with very lame dialogue that could put anyone to sleep (Daniel Neer as Bumerli and Suzanne Woods as Nadina, John Pickle as Alexius).

The Newport Classic album of “The Chocolate Soldier,” based on a new Ohio Light Opera translation.

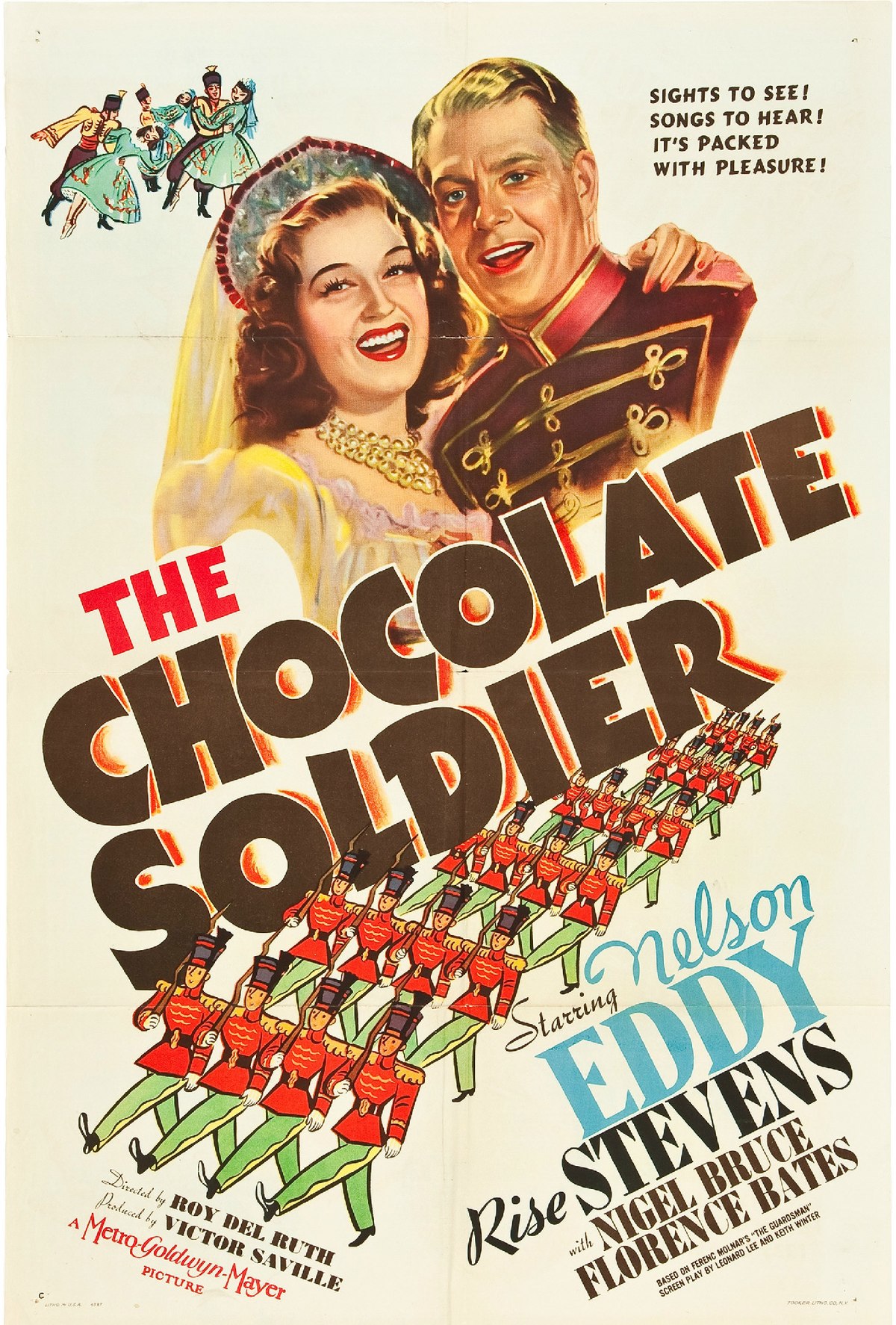

That’s not to say that there aren’t any other US version available. For one, there’s a rather famous Hollywood film that documents the enormous success of The Chocolate Soldier in the United States. But: “Behind the success of The Chocolate Soldier there was a bitter little twist,“ Kurt Gänzl writes in The Enyclopedia of The Musical Theatre.

Film poster for the 1941 Hollywood version of “The Chocolate Soldier.”

“A tale of a gesture which rebounded on the author of Arms and the Man, who had had to suffer the indignity of seeing the unconsidered Stange’s re-Englished version of his work far outrun not only the original play but any and all of his play to date. Shaw, who had sneered consistently at the musical theatre through his life and his career as a critic, had always insisted that it was not possible to musicalize his works. When permission was sought for the making of an Austrian musical of Arms and the Man he consented, but refused to take any royalties and postulated that a disclaimer be printed apologizing for the liberty taken in ‘burlesquing’ his play. His principles were clearly hurt when he saw the money made by The Chocolate Soldier and he discarded them in typical fashion when permission was sought to make the show into a film. This time he demanded big money. But he didn’t get it. All MGM needed was the title and ‘My Hero’, neither of which belonged to Shaw, and they took these and pasted them into a version of Ferenc Molnár’s A testör instead. Nelson Eddie and Risë Stevens starred in a 1941 film which had virtually nothing of Der tapfere Soldat or The Chocolate Soldier about it. But no one knew that till they got into the cinema.”

(There had been a silent movie version by the Daisy Film Company featuring Tom Richards as Bumerli and the producer’s sister-in-law Alice Yorke as Nadina.)

Risë Stevens later joined baritone Robert Merrill in 1958 for a substantial recording of The Chocolate Soldier on RCA. It’s not complete, and much of the music has been moved around. “It is a shame it could not have been done with a little more spirit and gaiety,” we read in The Blackwell Guide to the Musical Theatre on Record (1990). In this book Kurt Gänzl goes on: “The performance is too often rather like old-time D’Oyly Carte, and much of the blame for this must go to the shoulders of Lehman Engel and his orchestra, who are square and unimaginative when they should be gay and comical.”

The RCA album of “The Chocolate Soldier” starring Risë Stevens and Robert Merrill.

As for Risë Stevens, Gänzl writes: “her rich, mature mezzo-soprano sounds quote ridiculous singing the light, often soubrette, soprano music of the nubile teenage heroine of the show.” But there is Robert Merrill who “lightens off his voice splendidly” as Bumerli and sings “with humour.”

On the Capriccio disc no dialogue is included. On the Vienna version you get snippets of action, and a narrator. Though on the version made available by Spotify the dialogue is omitted. But on the disc issued by Hamburger Archiv für Gesangskunst you get the entire radio narrative; which is actually quite helpful and good. Because the story of Der tapfere Soldat is essential, you can’t just reduce the show to the music.

Cutrain calls in Munich at the first night of “Der tapfere Soldat.” (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

With all of the above said, I truly hope that the Munich version comes around quickly on film. The reviews from Munich were unanimously positive. And the bits of music you can hear in the radio reviews sound promising, Anthony Bramall conducts.

Jasmina Sakr (Mascha), Maximilian Mayer (Major Alexius Spiridoff) in “Der tapfere Soldat” in Munich. (Photo: Christian POGO Zach)

It might seem a bit strange to have the suave Maximilian Mayer as Alexius in Munich, instead of him playing Bumerli, while you get the more ‘standard’ Daniel Prohaska as Bumerli and not as ‘conventional’ Alexius. But those are the typical casting secrets of intendant Josef E. Köpplinger who seems to shy away from trying more innovative things comparable to what Gorki Theater in Berlin did with Alles Schwindel or Barrie Kosky with his Oscar Straus productions. Maybe Munich isn’t ready for such an operetta revolution? On the other hand, Oscar Straus and his Der tapfere Soldat certainly are ready. So stay tuned!

Of course, MGM’s turn of the century musical,”Two Weeks With Love,” 1950, has nothing to do with “The Chocolate Soldier,” either, except to give Jane Powell a sweetly touching “I’m a young woman and proud of it,” moment when she gamely negotiates My Hero while wearing a form-fitting corset.

Of course, the Capriccio recording documents a Koln WDR performance from 1993, not 2012. The original 1909 version of the Chocolate Soldier on Broadway (which downplayed the Shaw anti-war message) has been revived and revised several times since then. The Rise Stevens, Robert Merrill highlights disc may be a little schlocky, but features two of the finest voices to ever sing musicals or operetta.

I would like to remind a wonderful studio recording by La voz de su amo (New York, 1931) which was remastered by Blue Moon (Barcelona, 2000). The recording shows a strong Spanish-Mexican cast directed by maestro Eduardo Vigil Robles and makes use of the most popular of the five (!) adaptations performed in Spain by zarzuela companies during the second and third decades of the 20th century. It deserves to be enjoyed!