Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

25 November, 2018

There are many events and exhibitions, TV documentaries and newspaper articles in circulations right now in Germany, commemorating the end of World War 1 and the following revolution in November 1918 that lasted till March 1919. At its end, the old social system of Kaiser and Wilhelmine empire was swept away, and Germany became a republic; for the first time ever. So, at first glance, it is not too surprising that Berlin’s Museum for Photography presents a show entitled Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919. But it’s the subtitle that should catch you attention: “Photography, Film & Entertainment Culture.” What that means becomes clear as you enter the grand exhibition room. The first thing you see there is a poster for the “Ballet Charell” from 1918, placed next to a photo by Willy Römer from January 1919 which shows three men with munitions fighting at Brandenburg Gate – onto which is plastered exactly this poster as advertisement.

The 1918 poster for the Ballet Charell, designed by Ludwig Kainer. Seen in the exhibition “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.”

Though I had seen black and white re-prints of this Charell poster before – from his time as a dancer, before he took over the directorship of the Großes Schauspielhaus and started presenting revues (An Alle, 1924) and the revue operettas that culminated in Im weißen Rössl 1930 – I had never seen the actual poster itself in full color. I must confess: it gave me a thrill, years after I presented the big Erik Charell exhibition at Schwules Museum where we had other original goodies, but not this poster. Nor this Willy Römer photo.

Advertisement for the Charell Ballet seen on the wall of Brandenburg Gate in a 1919 photo by Willy Römer. (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

The person in charge of the ‘entertainment’ aspect of the new exhibition is Evelin Förster, who many will know as a singer and author of books, among them Die Frau im Dunkeln about female authors and composers in the early 20th century. Evelin Förster owns a massive collection of sheet music with outstanding art works on the covers. And she has included many of these covers in the new exhibition. They surround the historic central section which is structured by month. So you get aisles that start with “November 1918” and move onto “December 1918” until you get to “March 1919.”

Curator Evelin Förster giving a guided tour of “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.”

While these central historic sections show the images you might expect, scenes of street fighting, demonstrations, election campaigns, returning soldiers, police actions, workers building barricades, executions etc., the entertainment aspect circles this well-known political history. Because in many of the street fighting photos you see advertisements for shows. The Ballet Charell is one of them. In her essay in the catalogue, Miss Förster lists the operettas that were on offer in Berlin during these months of revolution, all of them visible as posters on Berlin’s streets: Die Rose von Stambul at Central-Theater, Schwarzwaldmädel at Komische Oper, Wiener Blut at Metropoltheater, where Faschingsfee also ran, Die tolle Komtess at Berliner Theater, alternating with Sterne, die wieder leuchten, Das Dreimäderlhaus at Rose-Theater, Das süße Mädel at Neues Operettenhaus, together with Die keusche Susanne and Der Soldat der Marie; Drei alte Schachteln at Theater am Nollendorfplatz, together with Der Juxbaron. Then there was Polnische Wirtschaft at Thalia-Theater, Die lustige Witwe at Theater des Westens, Der Mikado at Palast-Theater am Zoo, Fledermaus at Deutsches Opernhaus and Graf von Luxemburg at Wallner-Theater. And, last but not least, Die Dollarprinzessin at Theater des Westens, as an alternative to Merry Widow.

Advertisements in Berlin in January 1919, combining political messages with show business. (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

It’s staggering to see how much operetta was played back then in the city. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Because there were also many revues, variety shows, and cabarets, often with the same stars as in the operettas. And there was film, the new genre that everyone was crazy about. (Fritzi Massary made a film version of ‘her’ Rose von Stambul in 1919.)

The 1919 book “Wie komme ich zum Film?” by Max Mack.

The exhibition has many amusing examples on the “film craziness” of those years, when nearly every young girl dreamed of being a star like Henny Porten and Pola Negri. A book by Max Mack is shown in a display glass box entitled Wie komme ich zum Film? (1919). It warns girls that a film career isn’t easy – unless you have the looks and the determination. And that it’s not about art but displaying your ‘goods,’ i.e. your body.

Pola Negri as Jeanne (Madame Dubarry) and Emil Jannings as King Louis XV in the Ernst Lubitsch film “Madame Dubarry” from 1919. (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

In some cases, the curators show how the mass demonstrations and angry street mob of the real life revolution is reflected directly on screen and in songs. For example you get to see the execution scene from Ernst Lubitsch’s Madame Dubarry (1919) on a monitor. The parallels to real life are frightful; and watching Pola Negri being dragged to the guillotine can still give you the chills. There is a light Lubitsch touch here, this is sheer terror!

The execution scene from Ernst Lubitsch’s “Madame Dubarry,” 1919. (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

The exhibition also focuses on the new films and songs that were made possible because of the revolution, a revolution that did not only sweep away the emperor and old political system, but also swept away censorship. As a result you get – for the first time ever – an ‘education movie’ about homosexuality called Anders als die Andern / § 175 (1919). It was made by Richard Oswald who later made many famous operetta films such as Die Blume von Hawaii with Marta Eggerth.

His ‘gay movie’ caused an outcry from conservative parties back in 1919 and had to be taken out of circulation for upsetting public morals. The Nazis later persecuted almost everyone involved in Anders als die Andern, especially Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld who opened his famous Institute for Sexual Sciences in 1919 in Berlin and worked as advisor for Richard Oswald.

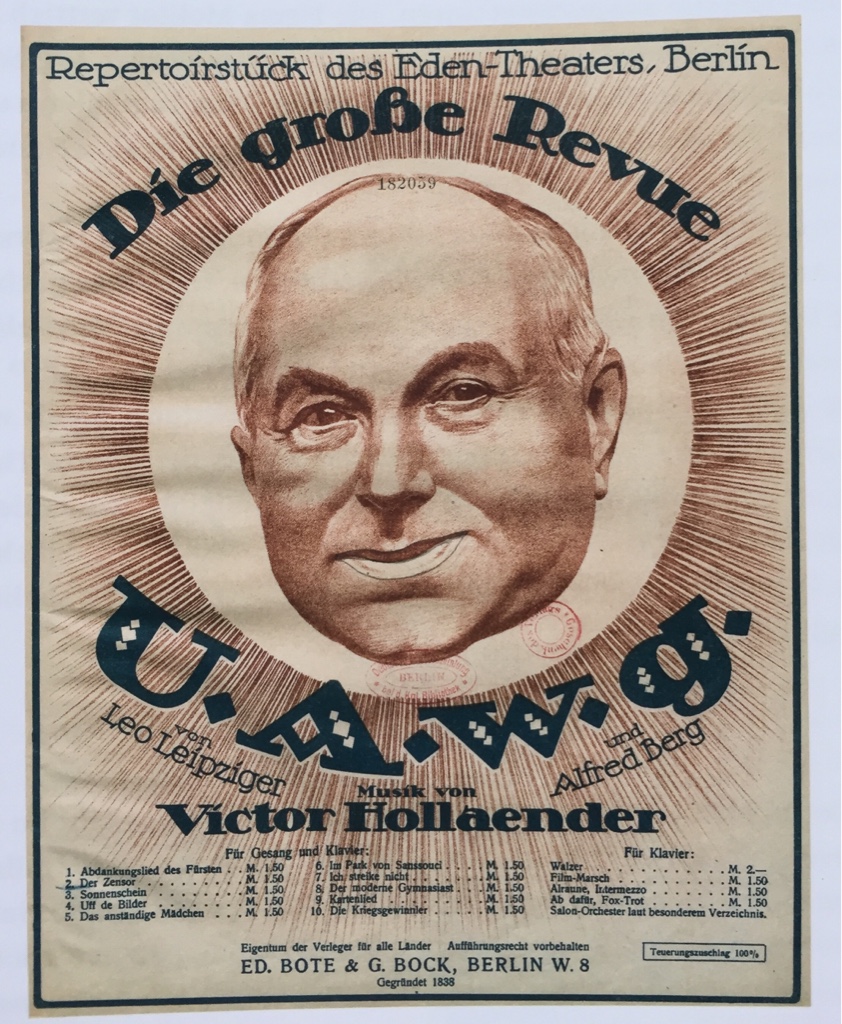

The grand revue “U.A.W.G” with music by Victor Hollaender, 1919.

Seeing scenes from this movie in the exhibition, seeing sheet music for popular songs that lament the lack of affordable apartments in Berlin (because so many soldiers returned and so many houses were destroyed by fighting), and reading the lyrics for Friedrich Hollaender’s “Fox Macabre” illustrates just how closely linked popular culture was (and still is) to central happenings in society and politics – long before the advent of people like Randy Rainbow.

In the exhibition, all texts are in German and English, so it’s easy to follow the narrative. The glorious catalogue – glorious because you can see the many postcards and sheet music covers with better light – is sadly only available in German. I’m not sure what the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin were thinking, because this surely is a topic that can interest international visitors and potential readers. In the catalogue there is an essay by Miss Förster on “Die andere Seite der Revolution. Aspekte der Unterhaltungskultur.” And there is also an essay by Alan Lareau on the cabaret “Schall und Rauch” situated in the basement of Großes Schauspielhaus (the title of the essay is “Der Lärm der Straße dringt ins Kabarett. Die Neugründung von Schall und Rauch“).

Looking at one of the sections of “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919″ at Museum für Fotografie.

For me, this combination of entertainment and revolution was refreshing and novel, and wonderful. It shows that we’ve reached a new level of operetta discourse that I would have thought impossible even two years ago. So, three cheers to the team who made Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919 possible, and especially to Evelin Förster for including all these wonderful music covers. She also includes a “nude dancer” in the exhibition, a new ‘public’ genre made possible by overthrowing censorship. Miss Förster did not opt for one of the famous nude stars, but for Erna Offeney who describes in her diary how she saw two soldiers in the front row at her performance. They both only had one arm, and they used to hand of the other to applaud enthusiastically. It brought tears to Miss Offeney’s eyes to see such a reaction.

The cover of the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.” (Verlag Kettler)

By the way, if you buy the catalogue at the museum it’s only 38 Euros instead of the regular 45 Euros.