Alan Lareau / University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh

Monatshefte, Vol. 108

No. 3, 2016

The lyricists behind our classic pop songs are generally unknown or forgotten. Robert Gilbert (pseuydonym of Robert Winterfeld, 1899–1978) wrote the words to enduring songs like “Das gibt’s nur einmal” and “Durch Berlin fließt immer noch die Spree,” and he penned lyrics for Weimar-era film musicals such as Die Drei von der Tankstelle (1930) or Der Kongress tanzt (1931), as well as operettas and stage musicals, most famously Im weißen Rössl (1930), which went around the world and is still performed today.

Christian Walther’s “Robert Gilbert. Eine zeitgeschichtliche Biografie.” (Peter Lang, 2016)

The son of operetta composer Jean Gilbert (1879-1942), Robert on occasion also composed his own melodies. While he produced songs on the assembly line for the entertainment industry, the engaged communist Gilbert also wrote powerful agitprop lyrics and political cabaret material under the pen-name David Weber in conjunction with composer Hanns Eisler (“Das Stempellied,” “Auf den Straßen zu singen”).

The most curious thing about his early career is how he was able to produce such polar opposites simultaneously.

In his first years of exile, he published anti-fascist poetry in émigré journals under the pseudonym Ohle. After emigrating to America, a period of hopelessness and isolation, he moved in 1949 to Switzerland and reclaimed his (West) German citizenship in 1957.

In addition to writing for Munich’s cabarets and publishing several volumes of verse, Gilbert enjoyed acclaim and fortune for his translations of Broadway musicals, from My Fair Lady to Annie Get Your Gun, Hello Dolly! and Cabaret.

Now he rejected communism and satirized his former ally Brecht, and eventually turned away from politics altogether. Among his correspondents were Hannah Arendt, the wife of his best friend, whose papers in the Library of Congress contain hundreds of pages of his letters and manuscripts; she wrote the afterword to a 1972 volume of his poetry.

Gilbert’s own papers are now held in the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, and the book at by Christian Walther is based on a thorough exploration of these archives.

The question of how to write a biography lies at the heart of this study, which documents a palpable struggle to find sense in the diverse and disjointed material that survives.

The Berlin cast of “Im weißen Rössl”, 1930.

Christian Walther repeatedly notes the gaps in our historical memory and the incomplete archival records, which reflect the turbulence of migration, war, exile, and the passage of time. An original letter from Brecht, which Gilbert displayed in a television interview but which is missing from the archives of his papers along with other important materials, and thus may still be in the possession of Gilbert’s apparently rather erratic widow, recurs as a key image of the narrative.

Many details can no longer be reconstructed with certainty, such as the circumstances of Gilbert’s October 1938 escape from Austria to France with stops in Berlin and Cologne to secure papers.

Walther also finds himself grappling with the published memoirs of Gilbert’s daughter (Marianne Gilbert Finnegan, Memories of a Mischling: Becoming an American, 2002), which he discovers to be riddled with half-truths and errors, albeit not intentional falsifications.

Marianne Gilbert Finnegan’s “Memories of a Mischling: Becoming an American.” (2002)

Through the surviving documents, Walther reconstructs personal stories including Gilbert’s difficult private and working relationship with his ex-wife, his alcoholism and depression during his late years, and his dysfunctional son’s tragic life. Unfortunately, these many bits and pieces can veer to the irrelevant and lose track of the core story, as in a lengthy passage on the possible dating of his first popular song, a long account of Arendt’s funeral (at which Gilbert could not be present), or a recounting of the Weimar film industry’s marketing strategies for their songs.

Even granted that this dissertation (FU Berlin) was undertaken in the field of Communication and is not a literary study, it is disappointing that Gilbert’s texts receive no meaningful evaluation, though many are reprinted in excerpts or in their entirety. A reader may well wonder, for instance, how Gilbert succeeded at transplanting the American musical to the German language. Walther liberally quotes Gilbert’s correspondence and contract negotiations throughout the genesis of his translation of My Fair Lady (staged in 1961) as well as his statements in the published libretto and an interview, but he never looks at any of the new lyrics to judge their techniques and effectiveness.

We learn that Gilbert did not like the musical Cabaret, but the one rendition quoted here (in its entirety), “Heirat,” only earns a cryptic reference to two lines in the original English (“Married”) without explanation; two passages from dialogue are then quoted, but ultimately there is no reflection on the translator’s craft.

These samplings are intended to be “exemplarisch” – but for what? One looks in vain for an assessment of why Gilbert’s work is considered “masterful” besides the fact that others have said so.

And just why was Gilbert’s German version of Godspell (1972) such a dismal failure? This is a valuable topic of cross-cultural literary and theatrical production that deserves attention.

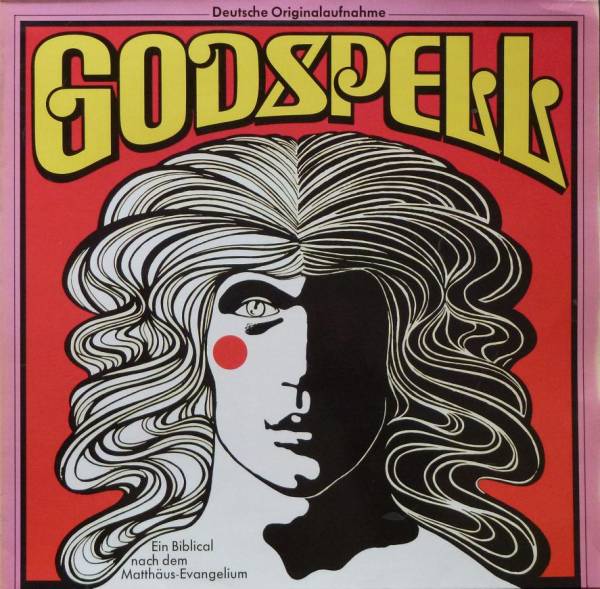

The German cast recording of “Goldspell,” using the Robert Gilbert translation.

In his introduction, Walther states that his study revolves around exile as the pivotal experience of Gilbert’s life, but this notion is not clearly demonstrated, for the life and work of the postwar European remigrant is far more thoroughly documented here. Later, he posits the argument that Gilbert’s “intensive Beziehung zur deutschen Sprache” is essential to his story, but this is not examined beyond its mere assertion. The text draws at length on other scholars (such as Albrecht Dümling’s work on Hanns Eisler) and contemporary reviewers, reprinting passages sometimes over a page long, yet Walther refrains from engaging with these ideas himself.

Instead, he merely uses these quotations as evidence that Gilbert’s work has been recognized and commented on by others through time. It is unproductive to quote at such length the business correspondence with the publisher Blanvalet over his book projects (and then note with frustration that no paperwork for later publications survives in the archives, an absence which this reader greeted with relief) or to print extensive passages from Gilbert’s and his ex-wife’s personal letters to and from Hannah Arendt that seem to be motivated primarily by Arendt’s fame. And one certainly need not include every bit of trivia one has discovered, down to Gilbert’s telephone number in 1927 or the amount of postage on a 1951 postcard to his publisher.

Robert Gilbert’s famous father Jean Gilbert, composer of operettas such as “Die keusche Susanne” and “Kinokönigin.” (1913)

The book is, in effect, a documentary montage, a collection of source material that gives a sense of the holdings of the Berlin archives, but it is not a successful narrative or analysis. Presumably in order to give his study a contemporary edge, Walther uses websites and online databases as sources, but footnoting Wikipedia entries for every artist mentioned along the way is pointless, and quoting lyrics from fan-generated internet collections instead of from the authorized, published scores and scripts lacks scholarly credibility. A systematic catalogue of Gilbert’s work would have been a useful contribution to scholarship.

Ultimately, the disappointment this dissertation evokes reflects a failure of advising at the dissertation level, for the research and writing clearly have not been adequately mentored and reviewed. Walther admits that his work has grown too long, but the problem is not just that there is too much unknown and unpublished material that deserves documentation, as he asserts, but that the study needs a clear focus and the discipline to present the material carefully and make an argument.

At least Christian Walther has called attention to the versatile career and highly creative work of Robert Gilbert, and posed the question of how we are to remember and reconstruct the stories of these forgotten and largely lost lives.