David Savran

Operetta Research Center

8 January, 2020

Stephen Sondheim’s Follies is the Mt. Everest of US-American musical theatre, his most searching and self-reflexive study of the genre he has revolutionized. No other work of Sondheim’s showcases the highly particularized pastiche song forms and styles that he uses in virtually all the Follies “show” numbers. No other musical reflects so systematically on the history of US-American song—and the theatre industry—and is as thick with ghosts.

Frederike Haas (Sally) und Christian Grygas (Buddy) in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

In Follies present and past, experience and memory are so tightly intertwined as to be virtually indistinguishable. Follies is also, with the exception of Assassins, Sondheim’s most US-American show, rooted in vaudeville, Tin Pan Alley, and the highs and lows, the manias and depressions of the Fabulous Invalid (which in 1971, the year Follies premiered, was in serious decline). Indeed, the reputed inspiration for the musical was a 1960 Life magazine photo of a begowned Gloria Swanson standing in the ruins of the then freshly demolished Roxy Theatre.

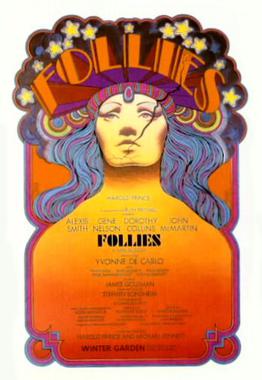

Poster for the original Broadway production of “Follies,” directed by Harold Prince.

Broadway Musicals in Germany

Despite the popularity of many US-American musicals in Germany, Sondheim’s work is far less widely performed than that of many of his compatriots, in part because Sondheim’s linguistic virtuosity, like that of Cole Porter, is a challenge to translate into German. Sondheim’s eccentric mixture of popular and modernist musical idioms, moreover, like Gershwin’s, challenges the antagonism that still prevails in many quarters in German culture between serious art and entertainment. Although Follies takes popular entertainment as its subject, it is far more aesthetically challenging than most Broadway musicals and it produced no major hit songs. It was not premiered in Germany until twenty years after its New York debut, in a fabled production at Berlin’s Theater des Westens which starred Eartha Kitt as Carlotta (singing “I’m Still Here” in English).

The Staatsoperette production marks its first in Germany since 1991 and its premiere in the former DDR.

Although the Staatsoperette has long produced Broadway musicals in addition to operetta, the company has mounted several especially notable productions of musicals since moving into their new house in Dresden Mitte in 2016. Nonetheless, when I heard that it was resetting Follies in Dresden in order to look back at the former DDR, replete with Soviet-era kitsch, I was (to say the least) extremely skeptical. Imagine my surprise when shortly into the show, I realized that director Martin G. Berger’s adaptation was managing successfully—and resonantly—to transport the ghosts of 42nd Street to “Florence on the Elbe.”

Gero Wendorff (Young Buddy), Florentine Beyer (Young Sally), Claudio Gotschalk-Schmitt (Young Ben) and Florentine Kühne (Young Phyllis) in “Follies” with the ruins of post-war Dresden in the background and typical DDR cars in the front. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

From Leuben to Kraftwerk Mitte

Berger resituates Follies in the new Staatsoperette while looking back at the company’s own history. When founded in 1947, it could not perform in the destroyed Altstadt and instead occupied a newly nationalized small, shabby theatre in the Dresden suburb Leuben (about 7 kilometers from the Altstadt). Construction on a new theatre in the abandoned Kraftwerk Mitte (built in 1895) began in 2014 and two years later the Staatsoperette moved into its much more luxurious and better equipped new theatre which, contained inside the Kraftwerk, evinces a palimpsestic hybrid analogous to Sondheim’s.

The new auditorium of the Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Stephan Floß)

Berger’s Follies however begins not in the Kraftwerk but with a huge video projection of the four protagonists arriving at the old house in Leuben, entering the building, and passing the ghosts of the showgirls of yore preparing for the show. They finally make their way through time and space to the stage, and end up not in Leuben but the new Staatsoperette—and the show begins.

Michael Kuhn (Roscoe) serenading the “Beautiful Girls” with the ballet company at “Staatsoperette Dresden.” (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

Because Follies uses the 30th reunion of the Weismann’s Follies as a pretext for the reconsideration and reliving of the past, Berger makes extensive use of pre-recorded video, which resembles a camera obscura projecting images of disappeared people, places, and things. He artfully underscores the ghostliness of this most haunted of musicals through the use of these spectral projections as well as the expansion of the roles played by the characters’ younger selves, who are more insistently and unsettlingly present than in any production of the musical I have seen.

A Trip Down Memory Lane

Berger’s split focus on 2019 and the 1980s means that the production also commemorates (and memorializes) the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the Communist Bloc, thirty years before.

Marcus Günzel (Ben) and the ballet dance in front of a Sovjet monument in “Follies” at “Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

Like Sondheim’s not quite nostalgic trip down memory lane, this production veers close to Ostalgie, juxtaposing a rose-colored communist past with the dour present, especially in the specialty numbers and the Loveland sequence. As Follies at last makes clear however in its big finale, “Live, Laugh, Love” in which dream becomes nightmare, that rose-colored past is itself unreal—fantasy, aspiration, delusion, and trap rolled into one.

Trapped in a time tunnel: Stefanie Dietrich (Stella), Dominica Herrero Gimeno (Young Stella) in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

Berger’s highlighting of the ghostliness of the present is visualized through Sarah-Katharina Karl’s scene design which, for the first part of the show, consists of three large, circular tunnels of lights on the theatre’s turntable in which and through which the characters and their younger selves perform. When the set revolves, these tunnels seem to become a mirrored labyrinth in which the characters appear and disappear.

Who’s That Woman?

The highlight of the mirror play was a spectacularly tap-danced “Who’s That Woman?,” performed by the six veteran showgirls and their younger selves, led by the thrilling Stefanie Dietrich as Stella (the choreography is by Marie-Christin Zeisset). Despite the emphasis on the past and the use of video, this Follies is always about the here and now of performance, particularly in the specialty numbers in which the no-longer-young Follies girls and their younger selves excel.

Silke Richter as Hattie in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

The actors playing the four protagonists may not have quite the long, eminent theatrical careers that Sondheim’s original cast had nor look as old as the play’s chronology dictates, but they powerfully embody the state of being marooned between an unfulfilled present and unrealized (and unrealizable) dreams. The Loveland sequence is appropriately spectacular scenically and choreographically while conveying Sondheim’s unique combination of showbiz glitz and despair. The choice to place the young couples singing “You’re Gonna Love Tomorrow/Love Will See Us Through” in pastel colored Trabants in front of the firebombed ruins of the Frauenkirche, silhouetted against a picture-postcard sunset, seems to epitomize the production’s eerily seductive use of Ostalgie as hallucination. For Berger’s DDR is a storybook land from which the Stasi, deprivation, and autocracy have been airbrushed out.

Beate Korntner (Young Heidi), Ingeborg Schöpf (Heidi Schiller) and Frederike Haas (Sally) in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

The Original DDR-Evita

Although all the performers turned in what I thought to be surprisingly idiomatic performances, I want to single out Bettina Weichert (who in 1987 played the title role in the original DDR production of Evita) as Carlotta who sings the one radically rewritten song, an “I’m Still Here” as narrative of survival not in Broadway and Hollywood but in the DDR. Berger’s use of the song to close the first act (instead of “Too Many Mornings”) powerfully highlights the East Germanness of his reimagination of the history of popular entertainments. Frederike Haas as Sally sings a heartbreaking “Losing My Mind,” while Marcus Günzel plays “Live, Laugh, Love” (with the very lively, very gold laméed corps de ballet) as the extended mad scene it is. Especially impressive however is Franziska Becker as a statuesque, bitter, driven Phyllis whose superbly danced and sing “The Story of Lucy and Jessie,” replete with a line of half-naked chorus boys, is the highlight of the evening.

Florentine Kühne (Young Phyllis) and Claudio Gottschalk-Schmitt (Young Ben) in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

I have grown accustomed to seeing Broadway musicals performed in Germany on a much larger scale than is standard in New York and the Staatsoperette Follies, beautifully and idiomatically conducted by Peter Christian Feigel, represents an impressive feat both of realization and transposition. I fear, however, that there is now a gold lamé shortage in Germany given the acres of the fabric that obviously went into the many, many costumes, designed by Esther Bialas.

A Measure of Authentic East Germanness

On balance, they struck me as rather tacky by Broadway (or Staatstheater) standards, but I suspect that that tackiness was deliberate and in fact gives them a measure of authentic East Germanness. It also suggests that at least some of the costumes (like the performances) have been pulled from stock, which is in fact a perfectly sound inference to draw about the goings on at this 30th reunion.

Franziska Becker (Phyllis), Marcus Günzel (Ben), Bryan Rothfuss (Theodor Whitman), Ingeborg Schöpf (Heidi Schiller) and Kaatje Dierks (Solange) in “Follies” at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Vincent Stefan)

At the performance I attended, much of the audience was old enough to have lived most of their lives in the former DDR. That they responded so positively to the Staatsoperette’s quirky US-German hybrid is, I suspect, a sign of their own ambivalences not only about their relationships and life choices, but also about the histories they have lived.

For more information and performance dates, click here.