Manuel Brug

Operetta Research Center

20 December, 2021

One should have known this would happen. If you hire the 70-year-old Christoph Marthaler, you get exactly that: Marthaler. He stubbornly circles around himself, together with his time-tested set designer Anna Viebrock. Not able to break free from his own esthetic loop that once was novel and innovative in the way it reimagined time, but that’s now nothing short of sleep-inducing. When Marthaler applies his familiar stage principles to his own works it might still have charm. But when the nauseating Marthaler mask is applied to the works of others, it’s too often annoying.

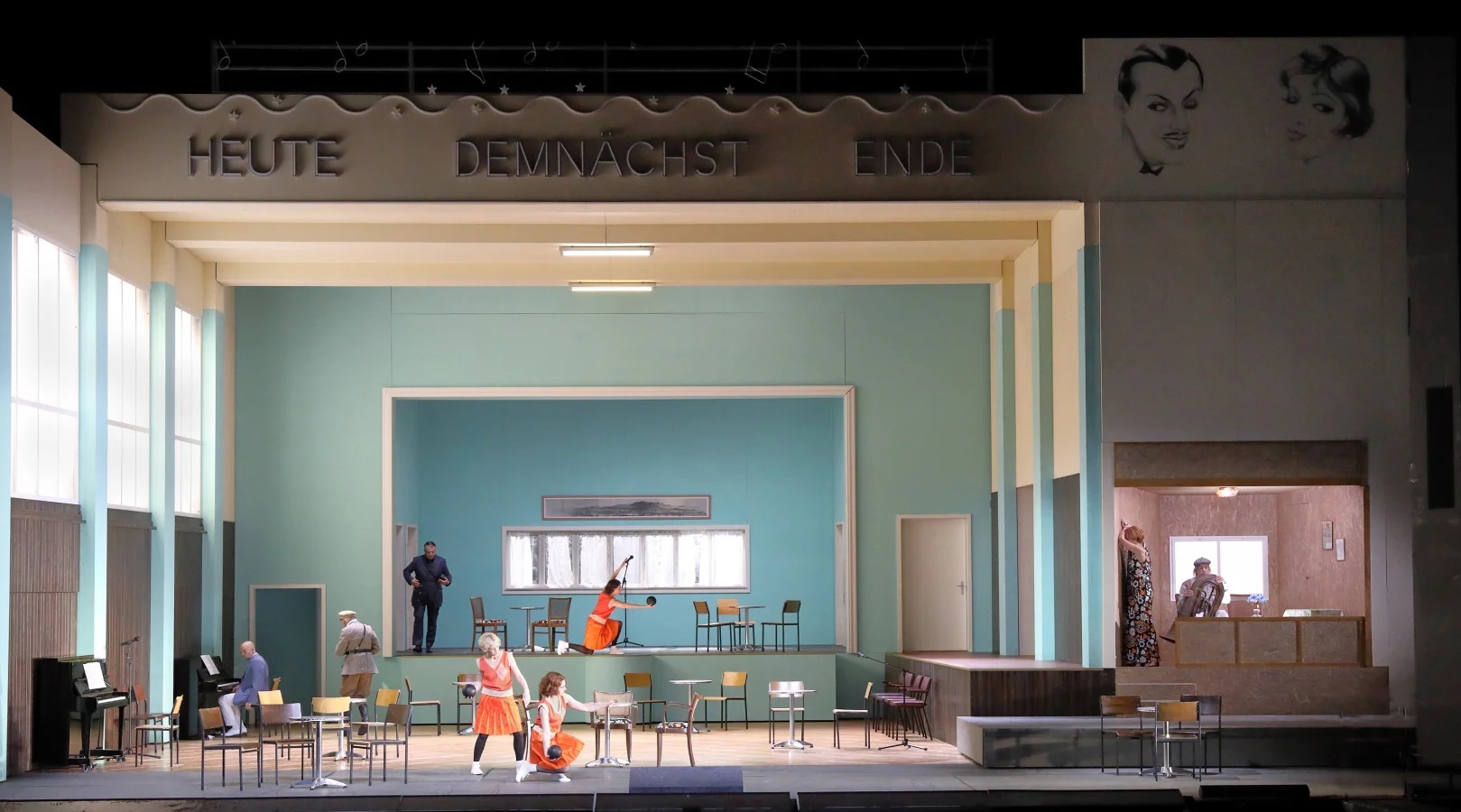

The sets for “Giuditta” by Anna Viebrock at Bayerische Staatsoper München. (Photo: Winfried Hösl)

This used to be different. There were times when the trained musician really delivered, e.g. in 1998 in Vienna and Berlin where he created a hilariously melancholic “socialist” version of Offenbach’s Pariser Leben. That same year he made his opera debut at the Salzburg Festival with a glorious Katja Kabanova.

It then took 23 years for him to make the 120-kilometer journey from Salzburg to Bayerische Staatsoper. There, in early summer and at the end of the era of parting director Nikolaus Bachler, he presented his simplistic Viebrock-vision of Aribert Reimann’s opera Lear. Which looked second hand and uninspired.

Now, under the new artistic director Serge Dorny, things didn’t fare better with Franz Lehár’s bittersweet Giuditta, a late work with trivial psychological twists and turns. It’s the first operetta after Fledermaus at the Bavaria Staatsoper – and Marthaler has turned it into a humorless and over-obvious protest against entertainment and fascism in times of radicalization.

To make this clear, an armada of theoretical deconstruction has been unleashed. For example, there’s the podcast with star-journalist Stefan Aust, talking politics and RAF terrorism (“Kontextualisierung, Verfremdung, Poetisierung”), but never mentioning Lehár or Giuditta or operetta in a single word. While another in-house podcast has two ladies singing “Meine Lippen, sie küssen so heiß” under the shower, hoping to reach new audiences.

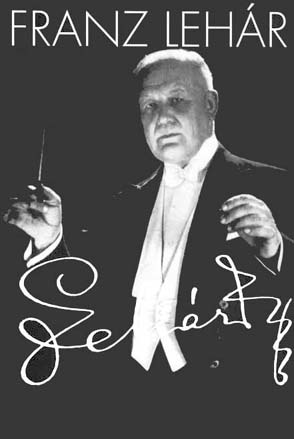

Franz Lehár with his star tenor Richard Tauber who premiered all of Lehár’s last operettas.

During Dorny’s reign at the opera house in Lyon, there was problem-free entertainment every year for Christmas. Now, audiences in Bavaria have to be educated about their bad conscience regarding popular musical theater, in an arrogant way that is highly problematic.

More problematic still is the fact that Viebrock considers the 1934 Giuditta, which premiered at the Vienna State Opera with Richard Tauber and Jarmila Novotna, a decidedly “stupid” show. Which is why the “Regieteam” decided to turn Lehár’s last operetta into a “project” in which only 50 percent of the original music remains in place. Such re-arranging of the score is possible because the copyright recently expired.

These helpless 50 percent, with all their brilliant kitsch and exotism, hot kissing lips and a sea in which you drown for love, are now “exposed”. How? By inserting “high quality” music from contemporaries who are politically less “damaged” than Hitler’s favorite composer, people such as Ullmann, Schönberg, Berg, Bartók, Shostakovich, Eisler, Stravinsky, Korngold, and Krenek.

Franz Lehár as an old man, conducting his own music.

But that’s not enough: the buffo pair gets a new terrorist story taken from Ödön von Horváth’s play Sladek oder die schwarze Armee, which turns the characters into bomb throwing bad guys.

For that to work, it would have been necessary to establish the original characters of Anita (a very unfunny and aloof Kerstin Avemo) and Pierino (Sebastian Kohlhepp singing with restrained tenor voice) as believable players in the plot. But here nothing is really staged or established. Everything is simply installed into the turquoise-beige sets by Viebrock, sets that seem recycled at least twice. They show a single large hall throughout, with a separée on the side (Viebrock refers to this as “eco friendly”). In this space – or “installation” – you get a lot of political debating. And not much else.

None of the characters are defined or taken seriously in this “focus point of a European panorama” (which is a nice phrase, but doesn’t mean much here). Instead, everyone is presented as a silly card-board figure. They are dummies singing either “worthy” material (the newly inserted music) or “sentimental toss”, i.e. cheap Lehár.

A scene from “Giuditta” at Bayerische Staatsoper München, with Daniel Behle in the front. (Photo: Winfried Hösl)

That affects the two lead roles especially, who act out a second-hand Carmen story set between Italy and Libya. Dapper Daniel Behle has a slightly undersized tenor-bang for this giant house and serves his big hit “Freunde, das Leben ist lebenswert” with wide arms and joviality. He, too, has to mime a dim-witted entertainer from start to finish. By his side, Vida Miknevičiūtė presents a dark and dramatic soprano as the revue dancer Giuditta, with deep-freeze eroticism, costumes that seem too intellectual and movements that poke around in thin air. Miknevičiūtė was heavily booed at the end, unfairly so, but the 550 people in the audience (a sold out house with only 25 percent attendance allowed due to Corona) needed to vent their frustration after three long hours of stoically sitting through all of this.

Of course, Lehár profited from the Nazi take-over in Germany and Austria, but he was a superstar composer long before 1933. And, yes, his last operetta Giuditta is a problematic piece written in very problematic times. Just like Emmerich Kalman’s Csardasfürstin, written during First World War. Peter Konwitschny once demonstrated how you can take such a show directly to the battle fields of WW1 and make the double layers of the plot and lyrics visible in a congenial way.

Marthaler only delivers gimmickry in Munich, a cheap and boring denunciation, with a few over-familiar elements from earlier productions reinstated: the slapstick-waiter, the lisping virgin (a virtuoso performance by Olivia Grigolli), the daffy resigned military (lead by the sleep-inducing Jochen Schmeckenbecher). Many members of the audience reacted with frustration and vehemence against this often infantile staging.

There is also a mini chorus of ten actors. And there’s a very loud orchestra of the Bavarian State Opera. Which leads to a lot of reaction-without-cause. Titus Engel might have a firm grip on this over-ambitious yet desolate Giuditta, and he differentiates the multi-layered styles. But when it comes to the opulent Lehár highlights, he lacks any sense of ecstasy, ambivalent humor, or even joy in presenting overpowering emotions.

By the time you reach the finale you can only join Octavio, sitting lonely at the piano, singing: “Schönste der Fraun, wo ist das Lied der Liebe, es ist schon längst verklungen. Es war ein Märchen…“

For more information and the stream in January, 2o22, click here.)

Het lijkt wel een epidemie dat respectloos omgaan met creaties van anderen. Misschien ontbreekt het aan inspiratie en kunde om zelf een stuk te componeren en een libretto te schrijven naar eigen goeddunken.Bah!

I have unfortunately read only a few sentences just to understand that art assassins continue to live in the theatre – in particular in Germany and Austria. Il faut se battre contre ces gens-ci. Io lo faccio e continuerò a farlo even if I prefer to forget.