Thomas Krebs

Operetta Research Center

3 November, 2024

He claimed to have written the lyrics for over 2,000 songs and to have been involved in “the making of two hundred and fifty bad movies”.

Ernst Neubach in 1960, as photographed by Keystone Press. (Photo: Archive Thomas Krebs)

Ernst Neubach was born into a Jewish family in Vienna on 3rd January 1900, the youngest son of a railway clerk. He attended business school and in 1915 won a prize in the shorthand writing competition “Stenographisches Jubiläumspreisschreiben” with 500 contestants, in the 80 words per minute category.

Not only his technical writing skills were highly developed at an early age; the youngster also knew very well what he wanted to write about and was not lacking in self-confidence. Contemporary news reports show that he appeared in public, reading his own texts, long before he came of age. One such event was a reading of young authors organised by the Writers’ Association “Die Scholle” in December 1916, in which he and another author read from their published and unpublished works. The earliest known publication was “Grinsende Masken”, in early 1917, which the Neue Wiener Journal called “ein Werkchen mit feinpointierten Humoresken und Satiren”.

Neither this nor a volume entitled “Satire und Leben”, published by Wolf in Vienna in 1920, can be traced in any library, however. What has survived, though, are pieces written for the journal Der Merker, in which the 17-year-old wrote about the development of the theatre or Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.

“Lieber Steffl, du…”

Another text, in which he asserted his intention to explain to the world at large what Gustav Meyrink’s Der Golem really was all about, earned him a negative review in the Prager Tagblatt which ended with the admonition “Laß es bleiben das Erklären, Herr Kannitverstan”. Undeterred, he continued writing prolifically, and for some years he was apparently known as Vienna’s “racing reporter”.

During WWI he served in the Austro-Hungarian army, from 1917-18, and was discharged after being injured.

In 1919 his two first song lyrics were published by Mändel in Vienna: “Lieber Steffl, du…” Wienerlied, with music by Carl Michael Ziehrer, who was Neubach’s senior by 57 years – and had dedicated the sheet music to his young friend: “Meinem lieben Freunde Ernst Neubach gewidmet”. The other was “Mausi geh’ komm’“, with music by Hans May, with whom he was to collaborate frequently in the years to come.

The years around 1920 were very busy ones for Neubach, with engagements as a conferencier in Munich: at the “Simplizissimus”, the “Kammerbrettl” and the “Kabarett Wien-Berlin”, and between 1920 and 1923 with engagements in “nearly all German variety theatres and cabarets”, as his lawyer put it in a letter to the restitution & compensation authority in Berlin in 1953.

His first full-length musical theatre production premiered in December 1922 at the Wiener Lustspieltheater. The book was by Pordes-Milo, the lyrics by Neubach and the music by Hans May.

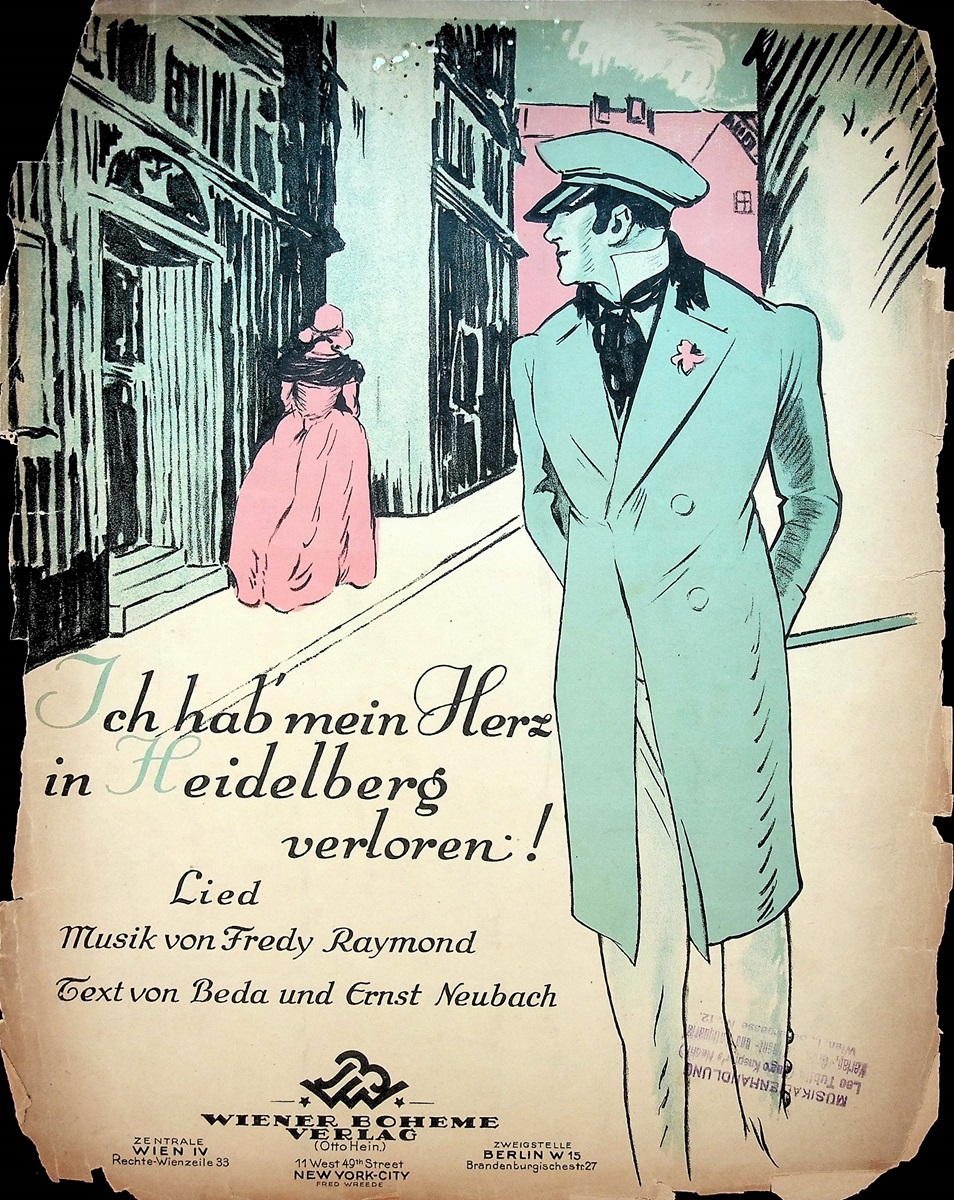

“Ich hab’ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren”

In the mid-1920s Neubach was based in Amsterdam for some time; in 1924 for instance, he took part in a touring performance of the Budapester Possenbühne.

Composer Fred Raymond.

In 1925 the song “Ich hab’ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren” (“I Lost my Heart in Heidelberg”) came into being almost by chance – as legend has it: The composer Fred Raymond (1900-1954), who had been commissioned by Schott publishers to write a “Rheinlied”, met Neubach, an inveterate gambler, who was on his way to Berlin to try his luck there, in a café at the station in Frankfurt. Both were short of cash. Raymond enticed Neubach to stay, telling him about two tall blondes, another weakness. Hurriedly Neubach jotted down the lyrics for the song on the back of the menu, and became cross when he realised that those blondes didn’t exist.

The song quickly became a great hit, and in 1927, the Singspiel based on it, Ich hab’ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren, premiered at the Vienna Volksoper – now with the revised lyrics by Fritz Löhner-Beda. The Singspiel was a huge success, with seven hundred performances in Vienna alone. In the early 1950s, when Neubach was in Heidelberg for a film shoot, he came across postcards in a print shop, all with the text “Ich hab‘ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren”, but no mention of any originator. The author, curious about his royalties, was told this was a folk song. When he revealed his identity as the author, he was told to come back with his birth certificate and prove that he was a hundred years old.

Ernst Neubach’s song “Ich hab’ mein Herz in Heidelberg verloren”, written with (Photo: Archive Thomas Krebs)

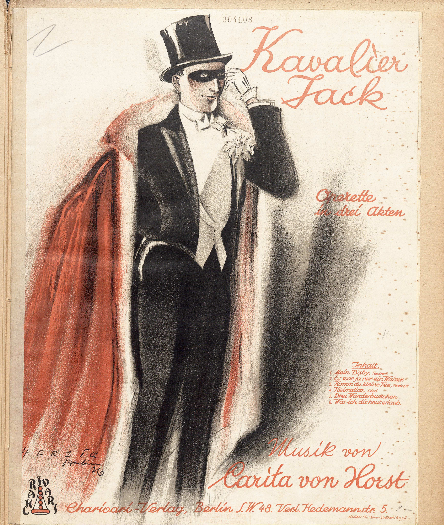

An Operetta Written with Baroness Carita von Horst

On 1 April 1926 the operetta Kavalier Jack was given its first performance, at the Thalia-Theater in Berlin. The music was written by a woman, Baroness Carita von Horst, née Partello, wife of the wealthy industrialist Baron Louis von Horst.

Carita von Horst at the first night party of “Kavalier Jack” in Berlin.

She had studied music in Stuttgart and had run a private opera school in Coburg. The libretto was by Theo Halton, the lyrics by Neubach, by far the youngest of the three authors. At 51, Halton was 25 years older, and the composer was already approaching her mid-sixties. Such a collaboration across the generations could obviously be successful: Kavalier Jack was staged in a new production as a summer theatre at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm and was eventually performed over one hundred times (for more information on that operetta, click here).

The sheet music cover of “Kavalier Jack.”

A couple of songs have recently been recorded by mezzo-soprano Patricia Hammond in her Living Room Requests programme.

A year after Kavalier Jack, another operetta with song texts by Neubach premiered at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm: Die Kleine auf Besuch by Hans Zerlett, with music by Robert Gilbert. Trude Lieske, Klara Karry and Oskar Karlweis played the leading parts. The director of the theatre at the time was Edi Winterfeld, uncle to Robert Gilbert (whose real name was Robert Winterfeld).

The foxtrot “Wollen wir nicht beide in die Hasenheide gehen?” from the operetta was recorded by Mizzi Metelka and Max Mensing and the Dajos Bela Dance Orchestra on Odeon.

In 1928, Neubach wrote the lyrics for the operetta “Prinzchen”, based on the play by Robert Misch, with a book by Günther Bibo and music by Rudolph Nelson.

Working with Jean Gilbert

Two years after Die Kleine auf Besuch he wrote the libretto for an operetta composed by Robert Gilbert’s father, Jean Gilbert (whose real name was Max Winterfeld): Hotel Stadt Lemberg, after the novel by Lajos Biro, was first performed in Hamburg in 1929 and subsequently staged in numerous cities in the German speaking countries, but also, under the title Marching By, in the Shubert Theatre in New York 1932 – where it closed after just twelve performances.

Jeab Gilbert at work with Gustav Charlé. (Photo: Phot. Willinger, Berlin / Theatermuseum Wien)

As a lyricist Neubach was of course chiefly known in German speaking countries but it did happen that he made it into the newspapers in other countries. One such occasion was in January 1930 when several US papers carried this note:

PRACTICES HIS PREACHING

(by United Press)

BERLIN—Ernst Neubach, who has acquired some fame writing popular song hits about beautiful girls he would like to marry, finally married one of them, the bride being Fraulein Hertha Langer, winner of last summer’s international beauty contest in Vienna.

Soon Neubach added his wife’s name to the list of pseudonyms he used – Konrad Drey, Roxy, Hans Joachim Bach, Johannes Fethke, E. Neuville and Hans Forge were the other ones.

Another great hit from Neubach’s pen, with music by Fred Raymond, was “In einer kleinen Konditorei” from 1929. This was commissioned by the Rotter brothers, theatre producers in Berlin, who required a hit song for a new production – Neubach’s adaption of a play called Gretchen.

Neubach’s Older Brother Robert

Neubach also wrote for revue productions, in Munich, Berlin and other cities, several of which were directed by his elder brother Robert. Robert Neubach (born in Vienna on 9 April 1891) was a theatre manager and a comedian and actor. In 1925 the brothers collaborated on a revue called Achtung Welle 5000, and three years later, on 13 October 1928 a detailed review was published in Der Artist – Das Organ der Varieté-Welt about the production of another revue, in Leipzig:

Die Neubach-Revue im Varieté Battenberg. Ernst und Robert Neubach haben es verstanden, das schon fast alltäglich Gewordene in ein neues Prunkgewand zu kleiden. “Ohne Kleid – tut mir leid!” nennt sich die neue Ausstattungsrevue. Alle schönen und heiteren Künste – Tanz, Gesang, Humor, und nicht zuletzt Schönheit, Anmut und Grazie haben an ihrer Wiege Pate gestanden und ihr sicher die besten Wünsche mit auf den Weg gegeben. Farbenfroh, mit märchenhafter Pracht ausgestattet, gleichsam in Silber getaucht, ist dieser Weg, den die Revue in 28 abwechslungsreichen Bildern schreitet, eins das andere überbietend in der prunkvollen Aufmachung, die selbst den verwöhntesten Geschmack, die heute recht hochgespannten Erwartungen an eine Revue befriedigen muß.

Die Dekorationen und Kostüme, von ersten Künstlern entworfen, von Walter Kollo, Fred Raymond u.a. musikalisch temperamentvoll und schmissig illustriert, am Dirigentenpult, im innigsten Einvernehmen mit den Künstlern, Kapellmeister Oskar Jerochnik, nimmt die Revue mit zwei artistischen Spitzenleistungen, den 3 Flying-Flacovis, mit ihren nervenspannenden Darbietungen am Sturztrapez, und Sun, dem urkomischen Jongleur, ihren Auftakt.

With the advent of talkies, a new field of activity was opened for Ernst Neubach, and soon he was not only busy as a lyricist or screenwriter but found more and more engagements as a film director and above all as a producer.

“Ein Lied geht um die Welt”

In Südwestfunk Radio’s film show in 1958, Neubach recounted how he met the famous singer Joseph Schmidt in director Richard Oswald’s apartment in 1932. Soon, a fruitful collaboration began between the two men, resulting in several films. It was Neubach who came up with the idea of using biographical aspects to find a suitable film role for the short-statured Schmidt in his first film as a leading actor. Due to Schmidt’s enormous popularity, the title ‘The People’s Singer’ was soon agreed upon – without, however, taking censorship into account. As a Jew, Schmidt was unthinkable as the people’s singer. The film could only be completed and screened because a song composed by Hans May, with lyrics by Neubach, was chosen as the title and sung by Schmidt in the film instead.

Ein Lied geht um die Welt (“A Song Goes Around the World”) premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo on 9 May 1933, and it was a major event. Josef Goebbels, who attended the entire screening with his entourage, was a great admirer of Schmidt, and, according to Neubach, he made the singer a huge offer if he remained on the radio, promising to make him an honorary Aryan. The next day, Schmidt escaped from Berlin. It was the day of the book burning. The film remained in cinemas and was an enormous box office success; it was only in 1937 that it was banned.

Like many other Jewish performers, composers and authors who had been drawn to the pulsating cultural metropolis that was Berlin in the 1920s and who were forced to leave Germany after the Nazi rise to power, Ernst Neubach returned to the Austrian capital in 1934. In the years before the Anschluss he was busy making films, mostly with his Donaufilm Gesellschaft in which he was active as an author, director and producer.

“Dokumentarischer Roman eines Heimatlosen”

After the Anschluss, on the night of 13 March 1938, Neubach barely managed to escape to Switzerland and from there to Paris, where he found refuge and met a man again whom he had a lot to be grateful for: Albert Göring, Hermann Göring’s younger brother, who had helped numerous people persecuted by the Nazis and who now supported Neubach again. Many years later, in 1962, Neubach was the first to write about Albert Göring’s good deeds, in the German weekly Aktuell.

Neubach described his experiences during his escape and subsequent exile in only slightly disguised form in his book Flugsand – Dokumentarischer Roman eines Heimatlosen (“Quicksand – The Documentary Novel of a Displaced Person”), which was published in Zurich in 1945 and in a French version in his own translation in Lausanne in the same year. Although the main character in the book is a textile expert called Josef Berger, he spends most of his time in Paris among émigré filmmakers. The names of some of the film personalities mentioned in the book can easily be deciphered such as that of the producer Gregor Rabinowitsch, who is called Mr Gregorowitsch in Flugsand; and Harry Sokal, who made some mountain films with Leni Riefenstahl, is easily recognisable in Harry Lakos.

When WW2 broke out, Neubach volunteered for the French army, but was first interned at the Stade de Colombe and later taken to the infamous camp of Meslay du Maine. After joining the Foreign Legion, he was brought to French North Africa and deployed as a forced labourer in Colomb-Béchar under inhumane conditions in the construction of the Trans-Sahara Railway. On 16 November 1940, he was finally released and was able to make his way to Juan-les-Pins. From there, he managed to escape arrest and deportation at the beginning of September 1942, and on 28 September, the refugee Ernst Neubach crossed the Swiss border at Collonge in the canton of Geneva.

His brother Robert was not so lucky. He also fled to France in 1938, where he was arrested in the summer of 1940. Accused of spying against Germany, together with his brother Ernst, he was charged with high treason, went through an odyssey of various prisons and camps, and was killed in Auschwitz in February 1943.

Escaping to Switzerland

After crossing the border into safe Switzerland – which, however, did not welcome refugees with open arms – Ernst Neubach voluntarily surrendered himself to the border police. He was first taken to a reception centre and then interned in various camps. However, he was soon deemed ‘unfit for camp life’ and placed in so-called private internment in a vacant hotel in Zollikon near Zurich. Later, he lived as a subtenant at various addresses in Zurich. During his entire stay in Switzerland, he was scarcely able to be active in theatre or film productions; the authorities repeatedly created obstacles. A biographical film about Henry Dunant, the script for which Neubach had written with the approval of the Dunant family, did not come to fruition.

In December 1943, the immigration authorities in Bern wrote:

Regarding the classification of the interned refugee Neubach, we are of the opinion that he is in no way qualified to be substantially involved in the production of the planned Dunant film. Furthermore, it is highly undesirable for a foreigner to have a significant influence on the making of a film about the life of an outstanding Swiss like Henri Dunant and to be allowed to put his stamp on such a work, which is intended to be typically Swiss in form and content.

When he wanted to do research for Flugsand in libraries in Zurich, he was initially not allowed to do so because it was undesirable for him to meet with other emigrants. The novel could only be published after it had been verified that Switzerland was mentioned only in passing and portrayed positively.

Neubach had never wanted to stay in Switzerland but planned to go to Hollywood. That did not work out, however, although he already had a visa.

After the war, Neubach, whose first marriage had ended in divorce and who had married a Swiss woman in August 1945, moved to France and became a French citizen.

He made a series of French films under the name Ernest Neuville, including several with Erich von Stroheim as an actor. From the second half of the 1950s on, he lived mainly in Munich and made light entertainment films with titles such as Tante Wanda aus Uganda or Wetterleuchten um Maria.

Ernst Neubach died in Munich on 21 May 1968. He had remained a French citizen until his death.