Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

3 November, 2024

It’s almost a quarter of a century ago that Laurence Senelick published his book The Changing Room: Sex, Drag and Theater, which analyzes various forms of cross-dressing in theater history. In it is a large section on the once famous cross-dresser Julian Eltinge (1881-1941) who appeared on Broadway in various shows that can be seen as early operettas. Senelick wrote, back in 2000, that it would be worth exploring Eltinge’s life further and that someone should tackle a full biography. Well, here it finally is.

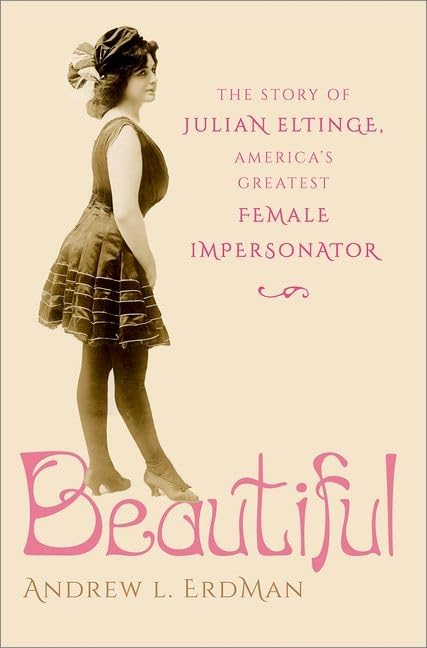

The new book “Beautiful: The Story of America’s Greatest Female Impersonator”. (Photo: Oxford University Press)

Andrew L. Erdman, who has a doctorate from City University of New York and who has previously published Queen of Vaudeville: The Story of Eva Tanguay, has presented a 350 page book called Beautiful: The Story of America’s Greatest Female Impersonator, published by Oxford University Press.

There are nine chapters, plus an introduction and an epilogue. They chronicle Eltinge’s life from 1881 till his mysterious death in 1941. The chapters cover the early years in vaudeville and on Broadway in shows such as The Fascinating Widow in which he played a college boy who goes ‘undercover’ as a woman to win back his girlfriend. He appeared in Jerome Kern shows, then went West and made successful films in Hollywood such as The Countess Charming (1917). In the 1920s he even had – in The Isle of Love – Rudolph Valentino as his on-screen sidekick.

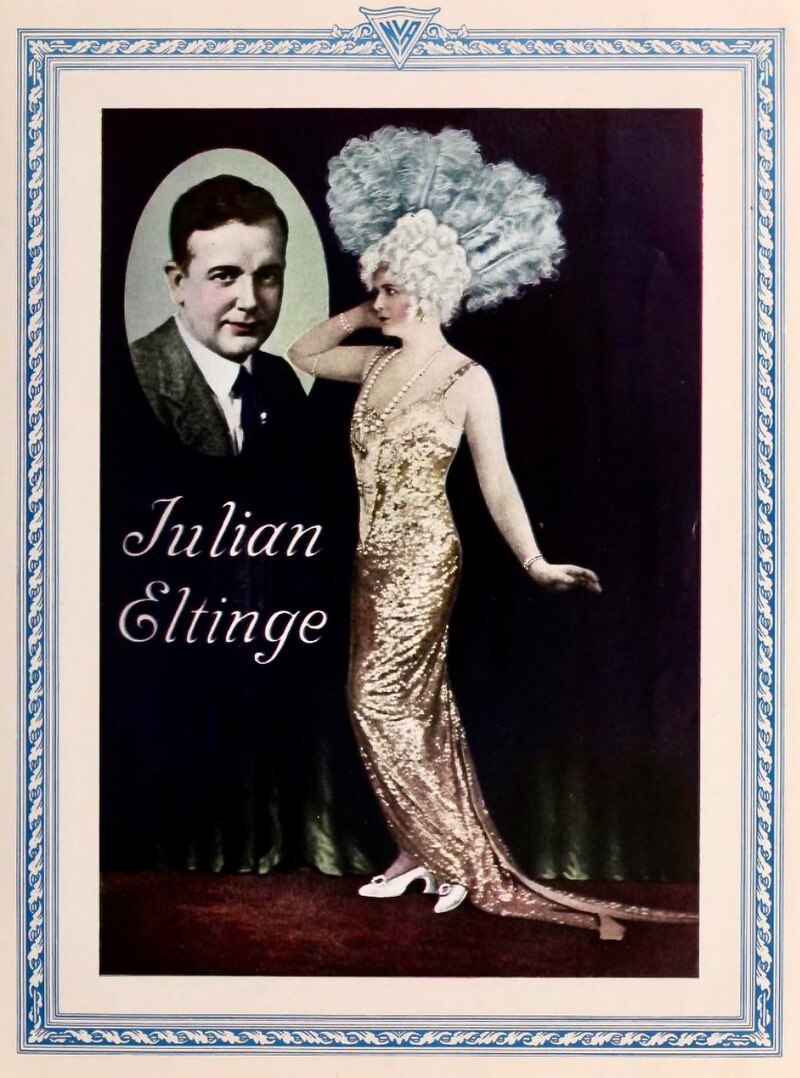

Julian Eltine in “The Fascinating Widow”. (Photographer unknown)

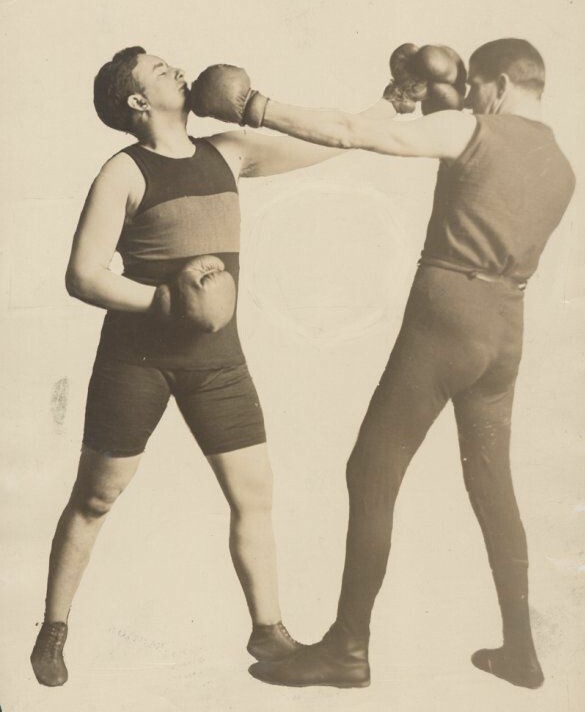

Eltinge – born William Dalton in Newtonville, Massachusett – had his own beauty magazine with tips for women how to apply make-up, how to dress and how to best make their man happy. There have long been rumors about his sexuality, which Senelick addressed. Eltinge took up boxing to present himself as a ‘real man’, he knocked out anyone who suggested he might be gay. And he supposedly said: “I’m not gay, I just like pearls.”

Julian Eltinge boxing in 1918. (Photo: The New York Public Library)

Erdman describes all this (especially in the chapter “The Velvet Inquisition”) but keeps a respectful distance, which some might consider a shame, other will like the book especially for it.

“I can see why LGBTQ historians have struggled with him over the years,” Erdman writes. “He’s not an easy ally. He didn’t align himself with other artists who were more comfortable with an emerging gay subculture, or gender fluidity. Offstage, he was sort of like this average guy who thought that taxes shouldn’t be too high.”

While Erdman couldn’t find concrete evidence that Eltinge had gay lovers, he suspects there were “erotic ties” to other men. Eltinge had some longtime friendships with men, especially when he lived in Los Angeles, but his personal life remains ambiguous. (Interstingly, Senelick is more straightforward here and names Eltinge’s long-term partner as a likely lover.)

There are many photos of Eltinge as a female stage persona, there are detailed descritpions of the various shows and films he stared in. We also learn which the craze for female impersonators of the early years of the 20th century stopped in the late 1920s and was replaced by a crackdown on cross-dressing and so called “pansies on parade”. Eltinge began to drink heavily. He lost his fortune in the stock market crash of 1929 and continued to perform in sleazy Hollywood nightclubs, he even appreared in a few late movies in cameo roles, e.g. in If I Had My Way (a Bing Crosby film).

Kenneth Anger in Hollywood Bablyon claimed that Eltinge commited suicide in 1941 by overdosing on sleeping pills. The officila cause of death, however, was “cerebral hemhorrage”. His funeral was attended by over 200 people. He was cremated and his ashes were sent to his mother.

Julian Eltinge as seen on the cover of a program in 1925. (Photo: NVA / author unknown)

“Why tell his story now?”, ask the reviewer of The Guardian. And gives this answer: “Conservative, homophobic groups have long stoked fears about the LGBTQ+ movement, and in recent years, drag queens have become a lightning rod in their culture wars, with performers facing death threats or protests from Republican or far-right groups. Eltinge’s story shows that drag has a long and complex history in the US, and was once widely considered a mainstream form of artistry – not a so-called affront to ‘traditional values’.”

The Guardian continues: “Though the drag one would find at a queer bar in 2024 owes much of its lineage to Black trans performers post-Stonewall, Erdman believes that you can still find Eltinge’s stamp on the ultra-realistic drag you might see go viral on Instagram or Pinterest today – ‘gender illusionist artists’ who use modern-day makeup to create ultra-realistic looks for social media.”

This is an important book on a famed theatrical personality, as Senelick points out in The Changing Room there are various others who had careers parallel to Eltinge whose life story is also worth telling in a biography.

In the best of all possible worlds someone like Ryan Murphy would turn the Eltinge biography into a mini-series and make it accessible to a wider public, as part of the (mostly) forgotten LGBT history of America – and operetta. It would also be very rewarding to have biographies of the notorious female impersonators in minstrel shows that are mentioned in Eric Lott’s Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy & the American Working Class.

The ‘dames’ that appeared there presented a sexually extreme type of humor that many today will consider racist to the extreme. But it was still a wa of talking about things (including queerness) that were otherwise impossible to say on a stage, so they are part of a liberation process that Offenbach and his librettists – in their different way – where also part of in Paris which shows like The Island of Tulipatan and its discussion of same-sex marriage. “Only connect” one might say, and put these various histories together?

The Albany Records release of Offenbach’s “The Island of Tulipatan,” 2017.