Mathias Spohr

Operetta Research Center

17 November, 2024

To speak of the genre of Viennese operetta as having a kind of Hegelian spirit, with a life course from its heyday to its swan song, is hardly common in recent literature. The works that have been assigned to this ‘genre’ are too heterogeneous, and the narrative of the decline of a so called ‘golden age’ that led to a ‘silver’ operetta era and then to a ‘bronze’ or even ‘tinny’ one (as an allusion to the repertoire of military bands) has rightly been branded anti-Semitic (click here for more information).

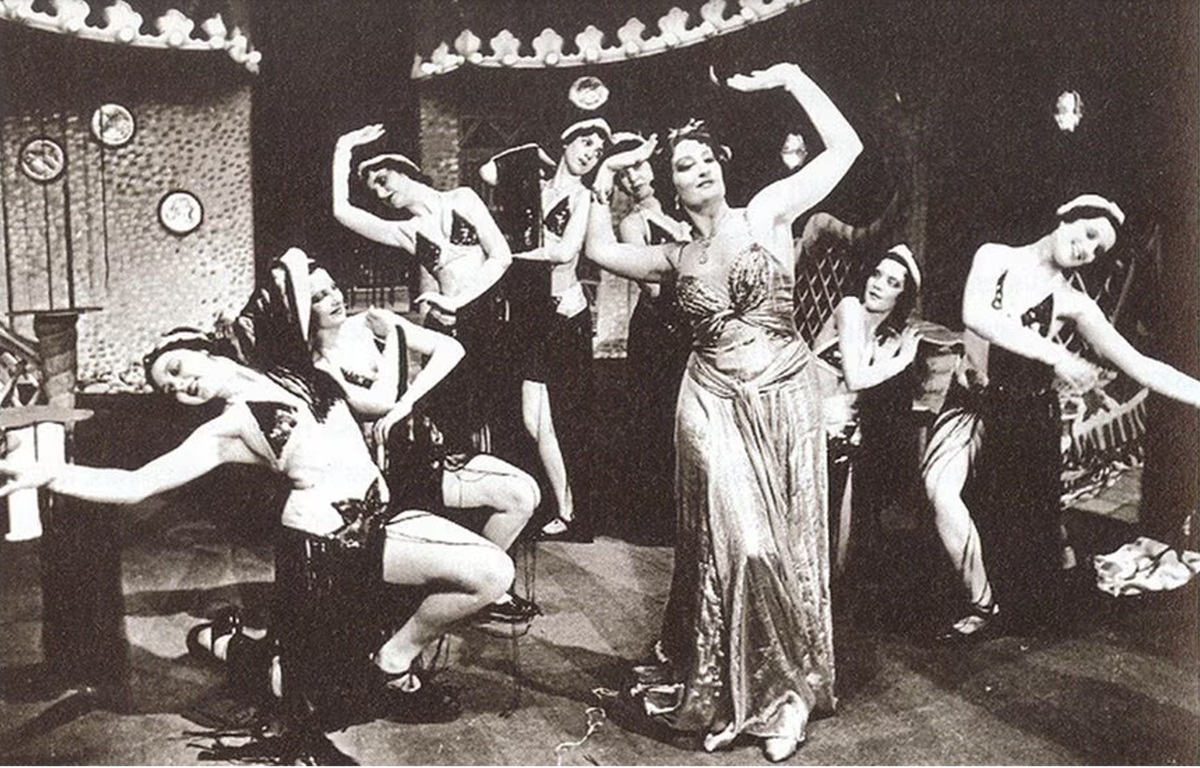

German ‘Ausdruckstanz’: Lehár’s “Giuditta” in Hamburg 1939. (Photo: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg)

A large proportion of the authors were of Jewish origin, as were the patrons, publishers, producers and audiences, and their suppression was heralded at the end of the 1920s. In fact, it was this suppression and subsequent annihilation that triggered a cultural decline. [1]

Far from being a swansong, Giuditta was the culmination of a development that came to a halt with the Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany in 1938. [2] For the first time, an ‘operetta’ was premiered at the Vienna State Opera, Austria’s leading opera house, and its success in January 1934 was boundless despite the adverse circumstances of the time. It was a historic triumph for Franz Lehár that his shows had now also conquered the stages of Paris, where in previous centuries the importation of theatrical works into the German-speaking world had originated. Since the Renaissance, Paris had been the most populous city on the European continent, replacing the cities of northern Italy, while it had lost ground to Vienna and Berlin since the end of the 19th century. The potential audience was the simple reason for the importance of theatre cities.

Franz Lehár (2nd from left) with his wife Sophie and George Gershwin when he visited Vienna in 1928. (Photo: Atelier Willinger / Theatermuseum Wien)

Operetta as a genre?

There is no such genre as operetta. The word is a diminutive, meaning either a ‘shorter’ or a ‘less important’ opera. The operettas of Jacques Offenbach or Franz von Suppé have, at most, only superficial similarities with the stage works of Lehár. Most of these shows did not label themselves operettas; their authors considered them to be operas of some sort, comic or comique or even bouffe. [3] Works in the vaudeville tradition were sometimes also referred to as ‘operettas’ despite their small amount of music because ‘operetta’ implied a ‘higher’ status for them. [4] If, on the other hand, the term operetta was used pejoratively, as was often the case later on, it could be applied indiscriminately to all objectionable music-theatrical works. Later ‘operettas’ up to Lehár were often understood in this tradition.

The world premiere of Giuditta was programmed between the episodes of Richard Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen, similar to an interlude in the late baroque opera. This showed a contrast between opera and ‘operetta’, although the work was not called an operetta.

Opéra comique and vaudeville are clearly defined genres: both have spoken dialogue between the musical numbers to ensure comprehensibility of the text, but vaudeville uses well-known melodies and opéra comique uses ambitious new compositions, and vaudeville was aimed more at the petty bourgeoisie and opéra comique more at the moneyed bourgeoisie. This was also the case with the German-language stage works of this type, especially as the translation and adaptation of settings was a common practice. Geographical names or dialects could be exchanged in the vaudevilles so that local audiences could recognize something familiar, whether in the Parisian banlieue or in Berlin, Vienna or Eastern Europe.

A Viennese operetta as a genre is, strictly speaking, an absurdity, even if authors such as Moritz Csáky [5] have endeavoured to give it an identity.

Moritz Csákys “Das kulturelle Gedächtnis der Wiener Operette”. (Photo: Hollitzer)

Stage plays performed in Vienna attempted to emancipate themselves from the French imports, but even a distinction between the major German-speaking cities of Vienna and Berlin in the production and performance of operettas is difficult to make, although Vienna could more easily present itself as a tradition-conscious city and Berlin as a progressive one, while urbanization and population growth were comparable in both cities. Viennese operettas were performed or premiered in Berlin and vice versa. It is difficult to determine what is specific, be it the subject matter or the origin of the authors, and there is no point in trying to do so.

Sheet music cover for Lehár’s “Giuditta.”

Giuditta avoids any ‘native’ folklore. Libya was not even associated with tourist clichés, only a seductive, distant and unknown Africa, depicted by a chorus of soldiers singing a kind of chorale with orientalizing embellishments, and the hotel lobby in the third act could be anywhere in the world. The Italian identity of the initial setting is as noncommittally exotic as the Chinese one in Das Land des Lächelns (1929), comparable to the clichéd Spain that French composers from Bizet to Ravel had reinvented. It was not until the musical The Sound of Music (1959/film version 1965) that Austrians became aware of a similarly shocking exoticism.

Selfishness and (or as) privacy

Giuditta has much in common with Giacomo Meyerbeer’s last opera L’Africaine (1865): the immense success of a final masterpiece, which was interrupted by war so that it no longer found its way into the repertoire, and above all the main character, who stands between two continents. But while Meyerbeer celebrated his great successes with stage portrayals of controversial political events from French or European history, Lehár achieved similar success with the consistent retreat of his characters into the private sphere. Profession or politics are annoying side issues.

In the prelude to Giuditta’s main plot, Pierrino auctions off his cart and his faithful donkey, Aristotle, in order to emigrate with Anita and start what he believes will be a great career as an artist. It is foreseeable that he will become a donkey himself. All the characters in Giuditta are in some way donkeys with their yearnings, the protagonists and supporting characters on stage, but also, and this is part of the effect of this kind of opera, the actors and the musicians in the orchestra pit, who all articulate their yearnings together and with ambivalent success. Giuditta, who has already gone beyond the comic happy ending of a bourgeois marriage, wants more, and she means it. An urge must be satisfied: Sigmund Freud’s serious world of instincts seems to have emerged and conquered comedy. Giuditta does not seem to want money, which could serve as the basis for everything else, but sex, to put it in modern terms; otherwise, after a duet about the pleasures of sensual love, she would not get together with a soldier.

The chosen Octavio has to go to Africa to put down one of these troublesome rebellions, as he mentions in passing. With the opera audience nodding their heads in sympathy, there is no need to discuss politics any further. The consensus about European superiority, in this case Italian rule in Libya, was still unbroken, and it seemed to be able to mask the growing conflicts of the inter-war period. Giuditta’s actions are not motivated by social or even political reasons (How would the biblical Judith have reacted? Giuditta speaks of her ‘people’ in Africa. What about her solidarity?), but personal, selfish freedom.

The urge for freedom and the renunciation of politics characterize a female role very different from Beethoven’s Leonore in Fidelio (1805/14), but also from Ilsa in Michael Curtiz’s film Casablanca (1942), which could be inspired by the final scene of Giuditta. Both Leonore and Ilsa fight for a just cause. Giuditta, on the other hand, is much more like her direct role model, Carmen in Georges Bizet’s eponymous opera. Because there was nothing exemplary about this leading character of an opéra comique, there was a scandal at the Paris première in 1875. Inadvertently, Lehár succeeded in repeating this scandal by sending his score to the ‘Duce’ Mussolini, who indignantly rejected it because he considered an opera with a deserter as the main character to be unperformable. His soldiers in Libya probably had good reason to desert. The realistic localization of the exotic world in a Libya colonized by Italy could not succeed. The interchangeable setting remained interchangeable, because that was the original intention.

Stigma

Charles-Simon Favart, the founder of the Opéra comique and the Paris opera house of the same name, once boasted that he had created entertainment for the aspiring bourgeoisie, for the “honnêtes gens”, and this expectation was still attached to the Opéra comique. Carmen is not honourable, she belongs to the underprivileged, who are denied social or even political activity. Although the librettists are careful to avoid stigmatizing Giuditta, she is stigmatized: she lives in Italy and her mother is from Morocco. Octavio is an officer, a little better than the guard soldier Don José, who is fascinated by Carmen, but his transformation into a bar pianist in a rumpled shirt is a social relegation. “Play it again, Sam”, like Rick in his café in Casablanca, he has to say to himself.

The protagonists of Giuditta are underdogs, even though they are the serious couple opposite the comic characters and ostensibly display social glamour. They do not benefit from the bourgeois values of women’s fidelity and honour as soldiers, but have to scrape by. Being unattached and having many men can also be a desirable goal for women, while the analogous male unattachment was and is a more openly articulated goal, especially in operetta. Since there were few career opportunities for women, the way to money was through men. This goal is difficult to condemn when there is no way. Bourgeois values presuppose a certain level of wealth and social status. It cannot be taken for granted that opera audiences will sympathize with these characters as they do in Verdi’s La Traviata (1853). The small and petty, which on the one hand seeks to liberate itself and on the other rebels against the anonymity and interchangeability that its liberation may cause or reinforce, is at the centre, and it is the art of the authors and performers that makes it admirable in silken costumes and opulent stage sets.

Comedy is the theatre genre of the bourgeoisie, and it therefore aspires to tragedy, because the citizens are taken seriously and do not want to be comic figures. The laughter in comedy is originally not laughter with, but laughter at. There is indeed a bourgeois comedy, but it is a comedy of laughing along, not of laughing at. The commedia dell’arte characters in Giuditta’s subplot are laughed at, whereas the audience can and should sympathize with the main characters Giuditta and Octavio, even if they are just as foolish. Contrary to all expectations, Pierrino and Anita turn out to be a faithful couple, the envy of Giuditta. Their distant departure is followed by a joyful return home to open a greengrocer’s shop, as in Favart’s operas. In the classical opéra comique, these faithful couples would be the serious ones and the fickle ones the comic ones. Here it is the other way round: Giuditta’s infidelity and Octavio’s desertion are associated with immense personal greatness.

Melodrama and dance

The bourgeois and even female soul, which suddenly appears as gigantic under the magnifying glass as the conflict of conscience of a noble general in classical tragedy, is the principle of melodrama. [6] It belongs to the genre of comedy, but is usually meant to be serious. Lehár’s music is such a magnifying glass for the protagonist couple. In Octavio’s entrance aria “Freunde, das Leben ist lebenswert” (“Friends, life is worth living”), the soldier’s youthful exuberance is given the most serious stylistic devices that fin-de-siècle opera has to offer.

Stefan Frey believes he can hear “Zarathustra kettledrums” in it. [7] This seriousness found consensus. The farewell scene between Octavio and Giuditta in the finale of the second act becomes a drama of the soul, whereas the scenic model in Carmen seems rather sober.

As Frey has pointed out, the librettists have put fragments of Nazi ideology into Giuditta’s mouth. She embodies the “African” quality that Nietzsche appreciated in Carmen (Der Fall Wagner, 1888). Bizet’s music “does not sweat”, as Nietzsche put it in contrast to Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (1865), and Lehár apparently tried to achieve the same with his music. Like Nietzsche, Giuditta uses quasi-religious vocabulary in an anti-religious way, combining it with the sensuality of dance. The National Socialists appreciated Nietzsche’s superman rhetoric as well as the performances of the then fashionable ‘Ausdruckstanz’, which made it possible to have a singer dance with dancers. [8] The dances were choreographed by the famous Margarete Wallmann.

Giuditta seems to be a sort of travestied Friedrich Nietzsche, who was able to articulate his unfulfilled desires with the powerful voice of a philosopher. All the interchangeable characters seemed to possess a certain greatness. The heroic seriousness of the ridiculous and trivial was not least a concern of Nazi rhetoric, and even the Jewish librettists of Giuditta, Paul Knepler and Fritz Löhner-Beda, took up this cause. [9]

In the drama on stage, Giuditta’s verbal, musical and dancing display of sensual dominance turns out to be a helpless, failing effort, and the authors were probably interested in this touching helplessness. The Nazi certainly did not like the (at least implied) decadence of this dance-like demonstration of power. The librettists’ aim was a common humanity, and so they had a risky sympathy for the sensitivities of the masses who were increasingly fascinated by National Socialism.

The fact that on this occasion the first opera house of the former Danube Monarchy joined forces to articulate the pleasure and pain of its own interchangeability, its lost or merely imagined identity, broadcast by a hundred radio stations, is a beautiful irony. Naturally, this event provoked furious reactions.

Instinct

Today it may seem embarrassing that in the most ambitious musical numbers, sexual intercourse is bluntly desired, and the only reason the depiction does not become pornographic is because it either ends immediately before the desired intercourse, or the sexual fulfilment turns out to be impossible or irretrievable. Kevin Clarke has pointed this out very clearly. [10] Sigmund Freud tried to absolutize desire as an ‘instinct’ that is common to all beings, as a technical energy modelled on the steam engine (to follow my interpretation).

The first operetta Giuditta: Jarmila Novotna in sensuous “gypsy” attire.

The singer as a libidinal powerhouse was an idol of the age, and his or her historical descent from the erotic-looking and sounding, but ‘gender-neutral’ castrati of Italian opera was hardly known anymore. In the 18th century, the interchangeable ‘baroque’ stage eroticism was transformed into a ‘classical’ gender identity. In the form of the trouser roles, however, the older idea remained like a ghost from the distant past. Conversely, it could be argued that ‘operetta’ is the legitimate successor to the old operatic tradition in a changed social environment. The older view (vanitas) saw desire as reprehensible, even though it was part of life; the newer view (identity) from the 18th century onwards saw ‘right’ desire as good, as opposed to ‘wrong’ desire. This explains the appeal of identities. The distinction between right and wrong desire, however, remained a problem.[11]

Jarmila Novotna and Richard Tauber at the opening night party of “Giuditta” in Vienna, 1934. (Photo: Photo Tanner, Wien / theatermuseum.at)

Generalizing and absolutizing, and the energy that resulted, was an emancipatory principle. It freed the individual from social barriers. The castrati were once physically and socially prevented from taking advantage of their freedom. But modern stars were allowed to do so. It was up to them and the world to decide whether they would make more of this freedom by entering into self-determined relationships, or whether they would fail in an anonymous world like Giuditta and Octavio. Giuditta’s “hot blood” is a justification for her liberation from Octavio, as it was initially from her husband.

The determinism of instinct rules fatefully and excuses even the inexcusable. According to Giuditta, it is even written somewhere in the stars: “Du sollst küssen, du sollst lieben. (“You shall kiss, you shall love.”) Her selfishness is an obedience, just like that of musicians who obey their musical notes and want to make a name for themselves. The interchangeability of relationships, characters, motifs and settings is lived out in this opera and taken to the extreme: Giuditta “must kiss another, can’t help it”, as Octavio confirms. Terrible as it is in the end, it is somehow all right. She is like an attractive picture that passes from hand to hand without being able to prevent it.

Emancipation or identity?

It makes no sense to tie this emancipatory motivation back to identities, be they German, Austrian, Jewish or even just male and female. ‘Operetta’, if there is a common characteristic of such works, is a symbol of emancipation, be it bourgeois emancipation from the aristocracy, sub-bourgeois emancipation from an established bourgeoisie, German-language or Austrian drama from French drama, and not least Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe from professional and social barriers. The word ‘escapism’ is too negative for this intention.

Emancipation goes out into the world, not into an ancestral environment, it believes in publicity instead of retreating into a snail’s hole. All this is deliberately interchangeable, the exoticism, the desire, the retreat into private feelings. It is inappropriate to call this an aesthetic flaw, because it is consistent. [12] The motivated step out into the anonymity of the big world that Giuditta dares to take cannot possibly be in harmony with any identity, and there is no point in attributing an identity to it, whether negative and stigmatizing or positive. If ‘operetta’ is supposed to serve the constitution of a contemporary identity, be it Austrian, Jewish or queer, then this is still in the tradition of the ‘German’ identity that nationalist voices have been trying to find in it since the end of the 19th century. Certainly, the later Johann Strauss, for example, adapted to such ideas, or at least tried to. But the efforts to create more identity overlook the fact that the majority of these works aimed to free themselves from a defined existence.

Music practice

Lehár called Giuditta a “musical comedy”, probably in reference to Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier (1911). Strauss was (and still is) the favourite composer of the Vienna Opera Orchestra, which is made up of members of the Vienna Philharmonic. He managed to strike a balance between the magic of sound and the polyphony and motivic-thematic work that was expected of a serious composer in the German-speaking world. Lehár sought to create two- and even three-part passages, rewarding tasks for the secondary voices in the orchestra and lush harmonies reminiscent of Puccini, but he never lost sight of the fact that there had to be numbers for the stars, which were to be separated from the work and performed with more modest instruments, such as those of the numerous spa orchestras and brass bands.

The composer had his score printed at his own expense. His publisher would not have bought it from him, as it was customary for operettas to be conducted from the piano reduction or a director’s score, which was sold or lent out together with the orchestral material. The orchestrations were designed in such a way that the same orchestral parts could be played in a variety of combinations and settings and still sound good, whether with a symphony orchestra of one hundred, a salon band of seven or a military band of twenty instrumentalists, in the opera, outdoors or in a coffee house. An original score, on the other hand, was only useful to conductors with the original instrumentation.

Interestingly, this great art of variable instrumentation is still not appreciated or even known today. The reason for this is that it openly reckons with the interchangeability of musicians and their audience, and interchangeability is a taboo, especially in contexts where it is obvious, such as with an orchestra whose voices are anonymous—especially with the chorally scored strings—and especially when their speechless and shared pain at their own facelessness is artfully articulated in yearning operetta melodies. In contrast to this de facto anonymity inherent in the system, identity is celebrated in the orchestra. All the exchangeable people at least sit in a certain place that they have conquered for themselves, not unlike the audience of theatre subscribers. For readers of scores and literature, the illusion of their own uniqueness should be maintained, and this applies to the performers in the orchestra pit as much as to their audience. For Lehár, therefore, the orchestral score as a series of unmistakable individual voices for unmistakable performers was the great step towards ‘serious music’.

Conclusion

The characters in the play are interchangeable, as are their partners, the settings are interchangeable, their performers are interchangeable, the musical numbers are interchangeable, the musicians in the pit are interchangeable, the venue is interchangeable, and the audience is interchangeable. The aim of this performance tradition, however, is the opposite perception: that unmistakable characters from an unmistakable environment appear in unmistakable works by unmistakable performers in an unmistakable theatre in front of an unmistakable audience. The paradox of this endeavour is particularly evident in operetta, and Giuditta takes it to the extreme.

This article was translated from the original German version to English by the author for the publication on the Operetta Research Center website.

[1] Cf. Steven Beller: Vienna and the Jews, Vienna: Böhlau 1993, pp. 31-34.

[2] See Kevin Clarke : “Gefährliches Gift. Die authentische Operette und was aus ihr nach 1933 wurde”, in: Operetta Research Center, July 2007. http://operetta-research-center.org/gefahrliches-gift-die-authentische-operette-und-aus-ihr-nach-1933-wurde/ (accessed 11/14/2024).

[3] For further reading: Mathias Spohr: “Inwieweit haben Offenbachs Operetten die Wiener Operette aus der Taufe gehoben?”, in: Rainer Franke (ed.): Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters, Laaber: Laaber 1999, pp. 31-67.

[4] Jacques Offenbach: « Concours pour une opérette en un acte », in : Revue et Gazette musicale, 20 July 1856, no. 29, p. 229.

[5] Moritz Csáky: Between Escapism and Reality. The Ideology of the Viennese Operetta (= Occasions 3), London: Austrian Cultural Institute 1997.

[6] Cf. Mathias Spohr: “Melodram”, in: Swiss Film Music Encyclopedia, https://swissfilmmusic.ch/wiki/Melodram (accessed 11/14/2024).

[7] Stefan Frey: Franz Lehár. Der letzte Operettenkönig, Vienna: Böhlau 2020, p. 302.

[8]Cf. Gunhild Oberzaucher-Schüller, Alfred Oberzaucher, Thomas Steiert (eds.): Ausdruckstanz: eine mitteleuropäische Bewegung der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Wilhelmshaven: Florian Noetzel 1992. Alys X. George: The Naked Truth. Viennese Modernism and the Body, Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press 2020.

[9]Mathias Spohr: “Der Golem und die Rührung. Auf der Suche nach dem Jüdischen in der Operette”, in: Isolde Schmid-Reiter & Aviel Cahn (eds.): Judaism in Opera/Judentum in der Oper, Regensburg: con brio 2017, pp. 225–261, see p. 235.

[10] Kevin Clarke: “La pornographie dans l’opérette”, in : Danielle Buschinger (ed.) : Érotisme et sexualité. Actes du colloque international […] à Amiens, Amiens 2009, pp. 315–325. Id.: „Sex in Operetten“ in: Kevin Clarke (ed.), Glitter and be Gay, Hamburg 2007.

[11] Mathias Spohr: “Identity and Vanitas. Two Contrasting Modes of Perception” (= Special issue of: Kodikas/Code. An International Journal of Semiotics, 43.3/4.2020), Tübingen: Narr 2025.

[12] This becomes even clearer in the technical medium of the ‘operetta film’. See Mathias Spohr, ‘Austauschbar oder unverwechselbar? Person und Funktion in der Filmoperette’, in: Günter Krenn, Armin Loacker (eds.): Zauber der Bohème. Marta Eggerth, Jan Kiepura und der deutschsprachige Musikfilm, Vienna: Filmarchiv Austria 2002, pp. 415-434.

Does anyone know if there is an English translation of the text in which Stefan Frey argues that the librettists have put “fragments of Nazi ideology into Giuditta’s mouth”?

I don’t know a translation, but what Frey states is something very obvious. Quotes such as ‘Die Erde trägt ihr Hochzeitskleid’ (Hermann Löns: Es singt der Star, 1924) or the “African” quality of the Carmen-like main character (Friedrich Nietzsche, Der Fall Wagner 1888) are not National Socialist in themselves, and the biblical vocabulary used in an anti-religious way can also be found in Bert Brecht, who cannot be said to have been close to National Socialism. But in this combination of elements, the proximity to Nazi rhetoric is obvious. Löns and Nietzsche were held in highly regarded by the Nazis. “Ausdruckstanz” was also used ideologically by the Nazis.

Thanks very much Matthias for your explanation. I have to say though that the idea that combining non-Nazi elements yields something Nazi is not obvious to me.

Also, inasmuch as Nietzsche appears to praise Carmen for her African quality, his attitude is on the face of it quite remote from Nazism.

Thank you, Alex, for your reply. Yes, the Nazis did not create original ideas, but combined existing ideas to form their world view. As you rightly say, there are elements in the libretto that do not fit with Nazism, mainly the failure of Giuditta’s ideology. The protagonists don’t find a relationship in the end. I believe that Giuditta is neither an affirmation nor a parody of Nazi rhetoric, but that the authors took up what was on people’s minds at the time. The boundless liberation of desire is what Giuditta has in common with Nazism. That was a hot topic at the time.

Thank you Mathias. I apologise for my having misread your article. I thought that the article was offering a critique of the librettists for their proximity to Nazi rhetoric. But inasmuch as your view is that this proximity involves no affirmation of Nazi rhetoric, I think I badly misinterpreted your position.Apologies.

No need to apologize, Alex! The theme remains difficult and interesting. The love duet between Giuditta and Octavio, certainly one of Lehár’s greatest achievements, does not say to the young couples in the audience: this is the desire you are allowed to have, take it as a model. It reminds me of the first love duet in opera that is considered expressive and touching, that between Nero and Poppea in Monteverdi’s ‘L’incoronazione di Poppea’(1642). It is the triumph of a ruling couple walking over dead bodies. With the same effect, it could be the love duet of a queer couple, showing the fascinating and ambivalent liberation of desire. In between is the period of 18th/19th century identities, such as gender identity or national identity. Nazism was a fundamentalist variant of this.

I can see why the Nero/Poppaea duet can be described as “the triumph of a ruling couple walking over dead bodies”. But it is not obvious to me that this description fits the Giuditta/Octavio duet or the duet of a gay couple showing the liberation of desire.

Desire is only presented, without saying at the same time: this is the good desire you should have!

I mean the following contradiction: The burning but apparently good desire for “Heimatland” or marriage in a Nico Dostal operetta is as ambivalent as any other desire. It can be inhuman if it marginalizes or expels others. Giuditta’s and Octavio’s sensual desire as a potentially dangerous energy is not necessarily good—it is more honest than a sentimental love duet. Am I still being unclear?

Thanks Mathias for your most recent comments. As I understand it, in order to explain the proximity of Lehar’s operetta Giuditta to Nazi rhetoric, you ascribe “boundless liberation of desire” both to the Giuditta love duet and to Nazism. You see the same boundless liberation of desire in the love duet at the end of Monteverdi’s Poppaea. What you say seems to imply that Monteverdi’s opera is proximate to Nazi rhetoric in the same way as is Lehar’s operetta. On the face of it, this view of Monteverdi seems anachronistic – I think it needs more defence than you provide. Also, inasmuch as you contrast the Giuditta duet with the kind of love duet one finds in a Dostal operetta, you seem to imply that the kind of proximity to Nazi rhetoric that one finds in Lehar’s Giuditta is not found in Dostal. This implication of what you say surprises me. I think it needs more explicit defence than you provide. (I would have thought that the sentimentality that you ascribe to Dostal makes his work more rather than less proximate to Nazi rhetoric.)

That’s what I mean. The ideology of the romantic duet and of love of country (good desire!) is closer to the fundamentalist Nazi ideology than to the neutral and ambivalent representation of desire that we see in Poppea and then again in Giuditta. The ambivalence of the I’m-pathetic-but-I-want-to-be-great attitude of Goebbels and his loyal audience, which Giuditta in a way shares, is harder to see as good than romantic love.

Apologies for completely misunderstanding you. I thought you were contrasting Lehár and Dostal to highlight the proximity of Lehár to Nazi rhetoric. So I assumed you were picturing Dostal as being less proximate to Nazi rhetoric than Lehár. Although I am embarrassed at having misread you so badly, I do strongly disagree with your contention that it is very obvious that Lehar’s “Giuditta” has a great proximity to Nazi rhetoric. Such a proximity may well exist. But it is not an obvious proximity.