Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

27 January, 2021

On 27 January, 1945 the Nazi concentration in Auschwitz was liberated by the Soviet Army. Memorial speeches all over the word commemorated this today, among them Charlotte Knobloch who addressed German parliament, warning politicians and the general population of a resurfacing of anti-Semitism. It made us at the Operetta Research Center wonder whether there’s any resurfacing anti-Semitism in our field, too? And contemplate why a hugely popular anti-Semitic terminology is taken for granted by almost everyone these days. We’re talking about the division of operetta history into “gold” and “silver.”

Gold bars representing the high value of that metal. (Photo: Jingming Pan / Unsplash)

Seriously? (We hear you ask.) So, before we go any further let’s take a moment to check when that gold and silver terminology first popped up. When Karl Westermeyer published his book Die Operette im Wandel des Zeitgeistes: von Offenbach bis zur Gegenwart in 1931 he did not (!) use these terms anywhere to mark 19th century vs. 20th century operetta. Instead, he speaks of Offenbach’s oeuvre as “Die klassische Operette,” and as a “zeitkritischer geistvoller Humorspiegel,” which translates as “a witty and humorous mirror critical of his times.” Westermeyer moves onto Vienna and calls the works by Strauss & Co. “Die romantische Operette” or: “Die Operette unter der Herrschaft des Wiener Walzers,” i.e. operetta under the dominance of the Viennese waltz.

After that, there are only subcategories. For example there’s “Die Zeit der Salonromantik,” the time of drawing-room romanticism. It includes Leo Fall, Franz Lehár, Oscar Straus and Oscar Nebdal. Emmerich Kálmán is grouped under “Wiener Volksoperette” (Viennese folk operetta). Then comes “Berlin und die Operette” with Eduard Künneke and others. Before the third mayor sections opens with “Gegenwartsprobleme.” There you find Dreigroschenoper praised as a model of a modern syncopated operetta. And the big question: where will it all lead to?

Of course we now know where it all lead to!

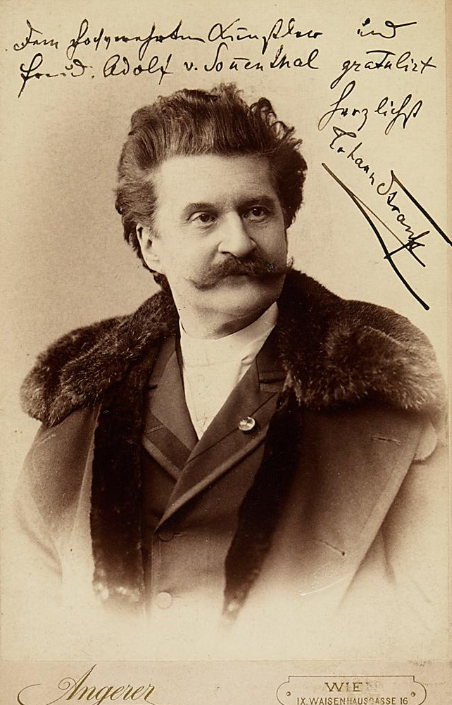

A late portrait of Johann Strauss, with his signature. (Photo: Victor Angerer / Theatermuseum Wien)

When Joseph Stolzing, a famous author for the Nazi propaganda publication Völkischer Beobachter, had discussed classic operettas as far back as 1912 he lamented that the “golden era” had sadly passed too soon. He talks of a “leider allzu rasch wieder entschwundenen goldenen Zeitalter.“ But nowhere does he mention a “silver” era that followed.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933 they had many new descriptions for operettas from the most recent past, the jazz infused Weimar years: these revue operettas were full of “negroid rhythms” and “ecstatic negroid movement,” which represented an “enemy negro curse for Europe”, a “feindliche Negergeißel” in Nazi terminology. They were examples of a “shameless derailing.” And of course they were above all else “Jewish.”

In 1938 Hans Severus Ziegler presented his exhibition (and catalogue) “Entartete Musik.” (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

So the new opposition was “Aryan” operetta vs. “Jewish” operetta. The old fashioned Viennese waltz works of Johann Strauss and Franz von Suppé, Karl Millöcker, and Carl Zeller (all non-Jewish composers, in the case of Strauss Goebbels fiddled around with the birth register) were recommended as a healing alternative to forget the “shameless derailing” that followed, plus the waltzing works of Franz Lehár whose Lustige Witwe was the official favorite musical theatre work of Adolf Hitler, ranking even higher in his esteem than the operas of Richard Wagner. Luckily, Lehár was another non-Jewish composer, as opposed to almost all his 20th century competitors and colleagues.

Moving forward to the end of the Nazi dictatorship, it was obviously impossible to continue using the “Aryan” vs. “Jewish” terminology after WW2. Even if the ideals stuck in the heads of many: the Viennese waltz works from the 19th century were still considered superior; and when it came to “modern” operettas there’s still only Lehár and The Merry Widow. It was downhill after that… right? But how do you describe that without immediately outing yourself as a Fascist?

In 1947 two clever Austrian authors, Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Otte, published their book Die Wiener Operette: Ihre Theater- und Wirkungsgeschichte at Bellaria-Verlag Wien. It’s part 2 of the series “Klassiker der Wiener Kultur.”

Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Otto, “Die Wiener Operette. Ihre Theater- und Wirkungsgeschichte,” 1947.

On page 297 we find the new magical word: “Das silberne Zeitalter der Wiener Operette (1901 bis 1920).” Of course this “Silver Age of Operetta” celebrates Lehár (what a coincidence) as the greatest of all the modern operetta composers. And after 50 pages this leads straight to the final – almost flippantly short – section entitled “Glanzvoller Ausklang (1920-1938),” basically grouping together everything that followed, as if it didn’t deserve any detailed account.

While the Hadamowsky/Otte book is hardly a classic, and most people will probably not even know it, the terminology introduced there stuck. And it still sticks. There’s no more talk of “Aryan” and “Jewish” operetta, yet their “gold” and “silver” in effect means the exact same thing, just wrapped in a different wording. Does that make it any less problematic and anti-Semitic?

The entrance to the concentration camp Auschwitz, which was liberated on 27 January, 1945, but the Russian army. (Photo: Stanisław Mucha / German Federal Archive, Deutsches Bundesarchiv)

Astonishingly, there doesn’t seem to be any interest in researching this further. The recent Cambridge Companion to Operetta uses the gold/silver terminology unquestioned, as does almost everyone else. (To read more about the Cambridge publication, click here.)

Perhaps the 27th of January is a good day to remind ourselves what this terminology actually means, and to ask if we seriously want to stick with something so ideologically contaminated 76 years after the end of WW2.

To learn more about Joseph Stolzing, Lehár and the Nazis, check out Stefan Frey’s new Lehár biography.

Dear Kevin, Thank you so much for this informative and eye-opening article! I’m new to operetta research and was indeed confused by this golden/silver terminology so your contextualization is very helpful.