Roland H. Dippel

nmz / Published in English with the author's permission

27 January, 2026

Like Berlin, Madrid in the Golden Twenties was a hotspot of nightlife and a queer mecca. On the evening of 12 May 1923 alone, around the Gran Vía some eighty music-theatre, entertainment, and cinema events took place alongside the world premiere of Pablo Luna’s zarzuela Benamor. “The boundary between propriety and taboo became blurred,” enthuses dramaturg and zarzuela scholar Enrique Majías García in the program booklet.

David Oller as Juan de León in “Benamor” at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Monika

Rittershaus)

One of the great idols of the era was Esperanza Iris, the “Queen of Operetta” from Mexico, who had commissioned the title role of Benamor from librettists Antonio Paso and Ricardo González del Toro specifically for herself. The success was immediate, triggering a chain of triumphs in Madrid, on tour, and throughout Spain that continues to this day.

Now Benamor has finally arrived at Theater an der Wien. Thanks to director Christof Loy’s devotion to the genre, zarzuela legend Milagros Martín, and an ensemble that shines down to the smallest roles, the result is pure music-theatre Viagra—for everyone.

The full “oriental” set on display in “Benamor” at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Monika

Rittershaus)

Loy’s turn toward zarzuela marks a major enrichment of his repertoire explorations. His El barberillo de Lavapiés in Basel was a clear number one; Benamor at Theater an der Wien, running since 23 January, is number two; El Gato Montés at Madrid’s Teatro de la Zarzuela will soon follow. These works function as analogues to familiar Central European formats such as Singspiel, revue operetta, or verismo drama—yet zarzuela is far more than a genre. It unites all genres.

In German-speaking Central Europe there remains an urgent need for catching up with regard to zarzuela. Isolated successes in recent decades, such as La generala at the Volksoper Vienna (2002) or Luisa Fernanda in Nordhausen (2016), remained exceptions. The applause went unheard; zarzuela is still treated here as an exotic curiosity. Shamefully so.

The composer Pablo Luna in Madrid, 1920. (Photo: Centro de Documentación y Archivo de la Sociedad General de Autores y Editores, Madrid)

At Theater an der Wien, the response to the genre is euphoric: cheers, bursts of laughter, open delight, and quieter smiles. Benamor is burlesque pushed to the extreme. To save her children’s lives, Sultana Pantea of Isfahan was forced to redesign and publicly conceal their gender identities. As a result, the young Sultan Darío is in truth a woman, while Princess Benamor is actually a man. As young adults, both sense that something is amiss: Darío, beneath his elegant-feathered turban, displays an inexplicable girlish shyness; Benamor wears Hussar boots under her skirt. Eventually everything is revealed, and everyone ends up happy—straight or queer alike—set to Iberian ease and sun-lit music for which Central Europeans deeply yearn.

Premium quality art is achieved across the board. José Miguel Pérez-Sierra instils the ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra Vienna with just the right sense of elasticity and swing. The Arnold Schoenberg Choir (director: Erwin Ortner), increasingly refined in its stage presence, sparkles as odalisques and as a guard corps eagerly willing to provide erotic “assistance,” adding touches that range from frivolous to slyly chauvinistic. The dance ensemble, choreographed by Javier Pérez, is first-rate, and the collective joy of performance is infectious.

Only one detail feels like a cheat. In the prologue, Milagros Martín—one of Spain’s great zarzuela legends for more than 40 years—as Sultana Pantea, together with Francisco J. Sánchez as the chief guard Alifafe, explicitly invites applause and da capo calls. When the audience enthusiastically complies, however, no one on stage responds. A pity, especially given the extraordinary density of hits in this part of Pablo Luna’s so-called “Oriental Trilogy.”

Marina Monzó as Benamor at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Monika

Rittershaus)

The “Paso del Camello” (Camel Dance), with drug dealer Babilon and his “merchandise” Nitetis (Sofía Esparza) prepped as a dominatrix, crackles with more fire than Eduard Künneke’s Batavia Fox from Der Vetter aus Dingsda.

The chivalric women’s hymn of the Ibero-Sicilian gambler Juan de León comes across as far more respectful than Lehár’s so-called “Women’s March.” Even seasoned visitors to Madrid’s Teatro de la Zarzuela will find themselves moving from one moment of admiration to the next in Vienna—especially in a house that recently achieved only partial success with Die Fledermaus for the Strauss anniversary.

Loy adopts original traditions of play and humor, sharpens the dialogue with care, and polishes everything in his uniquely refined manner—always with respect for the frivolous, the queer, and the all-too-human. On stage, zarzuela veterans and newcomers alike deliver a hedonistic yet affectionate firework of brilliant punchlines, indulgent light-heartedness, and genuine emotion. Even the young Pedro Almodóvar once trained himself on such theatrical forms.

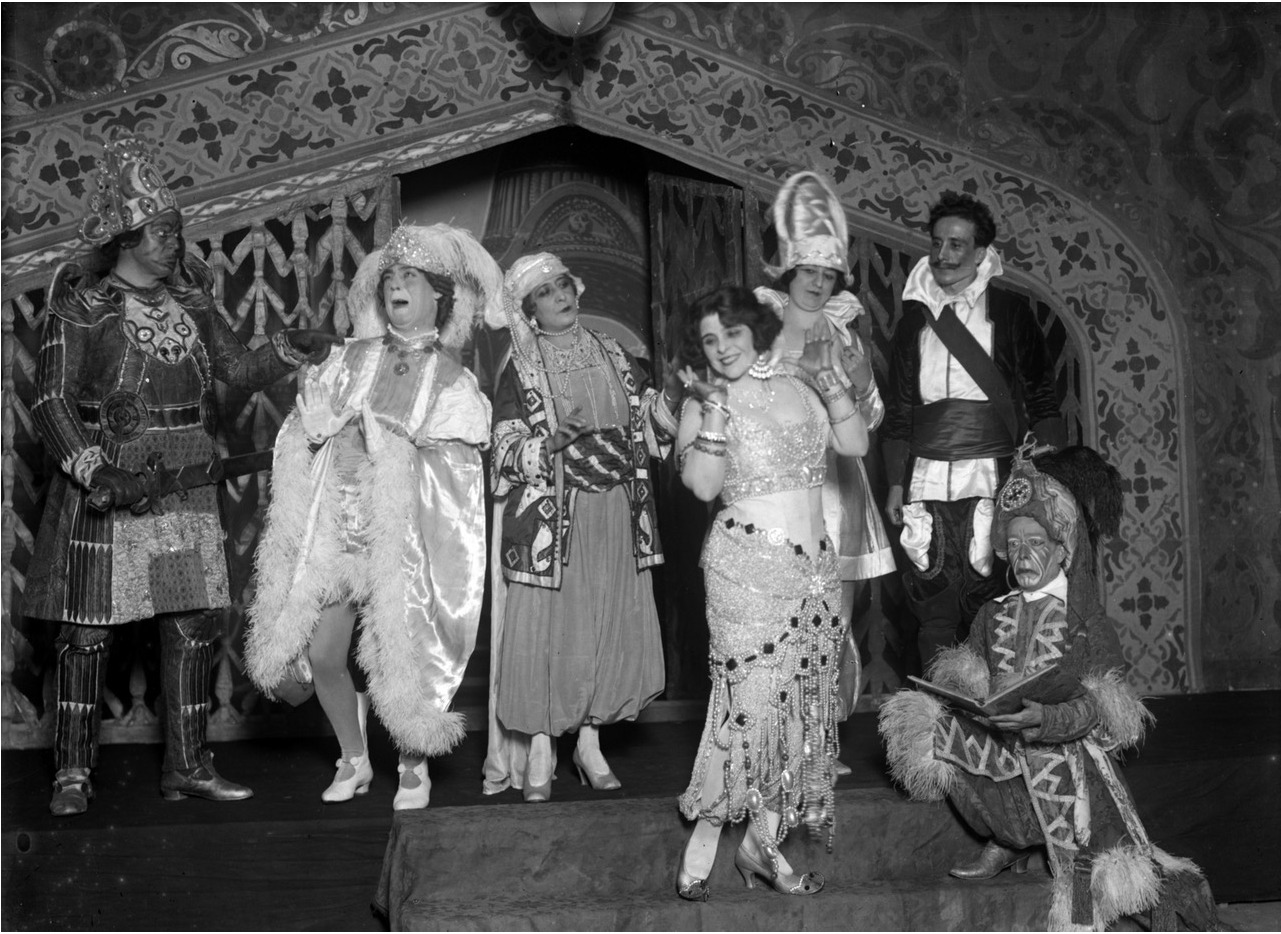

Scene from a “Benamor” production of the Esperanza Iris Company in Mexico City, 1924. (Photo: : Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexiko / Agencia Casasola)

In one respect, this Austrian premiere goes a step further than the opening night of 1923. Marina Monzó, who is a cross-dressed “dream man” with convincing macho attitudes (and a Carmen voice), is a binary mezzo-soprano. The role of her sibling Sultan Darío—originally portrayed by Mexican silent-film actress Mimí Derba—is sung by soprano Federico Fiorio with an ideal Rosenkavalier disposition. Anyone not consulting the cast list may need quite some time to sort out identities.

A glance at earlier Benamor productions, such as the Teatro de la Zarzuela’s 2023 staging, shows that “perfumed roles” with strong homoerotic appeal have long been a zarzuela specialty. Before and after the Franco regime, socially acceptable camp belonged to zarzuela as much as theatre-within-the-theatre in El dúo de la africana or travesty in La corte de Faraón. Carnival art thus repeatedly thumbs its nose at Catholic morality.

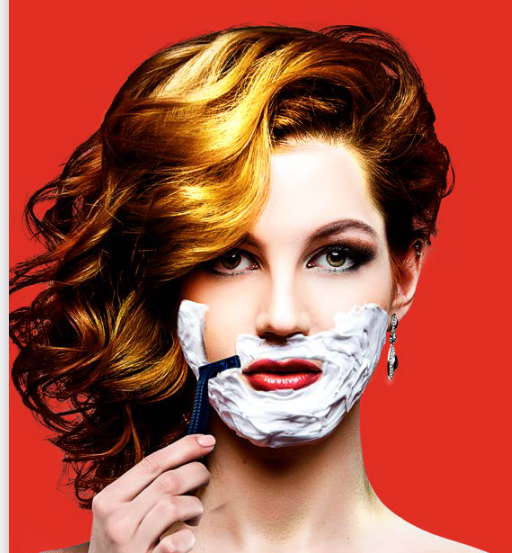

The official poster image (and cover of the program booklet) for “Benamor” in Madrid. (Photo: Teatro de la Zarzuela)

What is new in Loy’s reading is not merely that the flower prince Jacinto de Florella (delightful: César Arrieta) and the Afghan butcher Rajah-Tabla (likeable: Alejandro Baliñas Vieites) exchange love bites.

Stage designer Herbert Murauer, working with exquisite irony and increasing realism, and costume designer Barbara Drosihn gradually strip Pablo Luna’s erotic satire—loosely inspired by One Thousand and One Nights—act by act. After a day of chaos in the Sultan’s palace in Isfahan comes street life with caravans but without a bazaar. In the final act, everyone appears in black leotards: tabula rasa, partner choice without gender norms.

Dancers and ensemble in “Benamor” at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Monika

Rittershaus)

Above it all triumphs Juan de León’s praise of women, sung by David Oller with sword in hand and virile verve. There is also a reunion with David Alegret as Grand Vizier Abedul; 20 years ago, in Loy’s production of Il Turco in Italia for Hamburg and Munich, he was the much-adored Narciso. Here, Abedul becomes temporarily deaf after intimate encounters with women—and he has many such encounters. Only the beautiful odalisque Calchemira (Nuria Pérez) is inexplicably kept waiting far too long.

There would be more life-true details to tell. But one really should travel to Vienna and see it for oneself. Performances run until 7 February.