Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

21 December, 2017

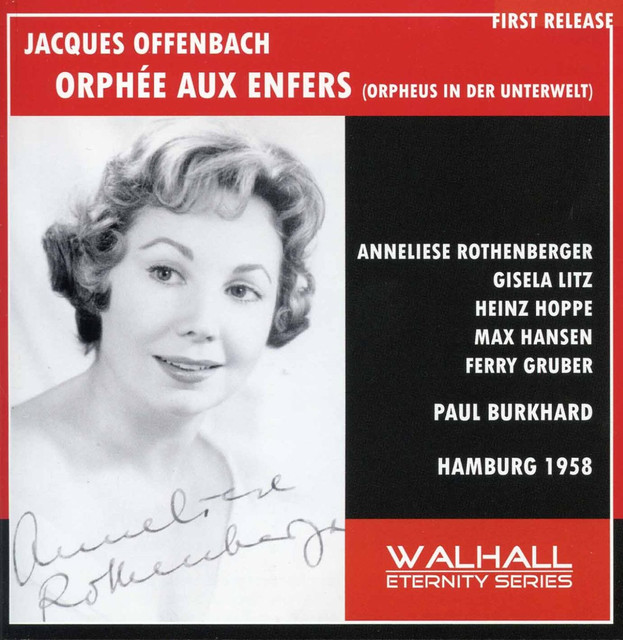

It’s an unusual coupling, to say the very least: Anneliese Rothenberger and Max Hansen in one recording? The hairspray-star of the 1970s, heroine of so many camp TV operetta programs and the most famous example of a latter-day opera diva in operetta-land, and the cheeky 1920s cabaret star who created the role of Leopold in Im weißen Rössl in 1930 at Erik Charell’s Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin? Well, it happened, and the document of this rare encounter is available as a full cast album of Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers, or rather Orpheus in der Unterwelt. Because this is a German language double disc, based on a NDR (North German Radio) production from 1958, conducted by Paul Burkhard. Yes, that’s the composer of Feuerwerk, the 1950s operetta super hit created by the same Erik Charell for Munich’s Gärtnerplatztheater and originally conceived for Max Hansen as circus director Obolski. (Who then didn’t sing the world-premiere.)

The cover of the Walhall Eternity Series “Orphée aux enfers” from Hamburg, 1958.

Listening to this Orpheus again, after all these years, is a treat. Because it reminds us of so many things that have changed. When Jacques Offenbach brought his Bouffes Parisiens to Vienna in 1861, the press reported that their style of performing (in French) was “mostly vulgar to the extreme” (“meist derb bis zum äußersten”), and that the dancing was full of “crazy chaos” (“tollste Ungebundenheit”). A year earlier, Johann Nestroy had presented Orpheus (in German) in Vienna at the Carl-Theater, in a “Burlesque” version of which a Vienna critic wrote “it took the tone of the piece down into the lower regions” (“den Ton dieser Burleske in gemeinere Regionen herabgezogen”). If you’re vaguely familiar with the coded language of reviews of 19th century Vienna, you get a pretty good idea how this sort of operetta performance worked, and why it was so immensely successful.

Gustave Doré’s vision of the „Galop infernal“, as seen 1858 in Paris.

A century later, in Hamburg 1958, Mr. Burkhard conducts a performance that is as un-vulgar as possible, and there certainly is no chaos or hint at lower regions. The Sinfonieorchester des NDR plays with classical perfection, highly restrained in energy, never going overboard. Not even in the famous can-can, which sounds – in this version – almost as harmless as a children’s jumping-song. The atmosphere of the whole production – which includes such fine vocal artists as the young Heinz Hoppe as Orpheus, the young Ferry Gruber as Pluto, the young Gisela Litz as ‘Die öffentliche Meinung’ i.e. L’Opinion Publique, and Hubert Glawitsch as Morpheus – is reminiscent of the Karl Richter Bach Cantatas and Passions. You need to un-hear what later Period Instrument pioneers did with Bach to fully enjoy the Karl Richter versions, which have recently enjoyed a tremendous comeback. The same is true of this NDR/Burkhard Offenbach. You need to forget what ‘could’ and ‘should’ be done in terms of sonic craziness with his score, and settle for perfectly proportioned propriety. Musically, it’s actually very rewarding (also because Else Mühl is a sumptuous Diana, Ursula Schirrmacher Venus and Erna-Maria Duske a clear voiced Cupido). But it’s staggeringly tame. With a few noteworthy exeptions, such as the Olympian revolution (“Zum Kampf, ihr Götter kommt herbei”) and the witty laughing ensemble “Um einst Alkmene zu betören.”

In the midst of all this, the young Anneliese Rothenberger. I emphasize the youth of all these artists, because nearly all of them, together, recorded Orpheus in der Unterwelt again in 1978 when the freshness of their voices – and possibly the innocence of their style – was long gone, and the result a very different and even more staggeringly tame affair. (On EMI with Willy Mattes conducting. With Theo Lingen as a historic ‘extra’ singing Hans Styx in a deliciously funny way.)

The EMI recording of “Orpheus in der Unterwelt,” 1978.

Hearing Rothenberger in 1958 is a revelation in terms of vocal beauty. It’s the time when she sang Sophie in Rosenkavalier for Karajan at the Salzburger Festspiele or at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, it’s the time when she sang Zdenka in Arabella next to Lisa della Casa. Her soprano is of such overwhelming grace and purity, there’s such effortless management of the coloratura, such clarity in the text … that you understand why Rothenberger had the career she had, also in operetta.

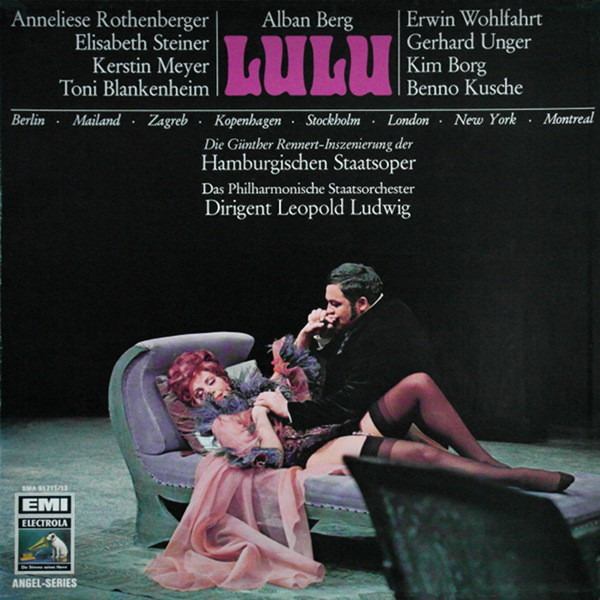

It’s a decade before she tackled Lulu at the Hamburg State Opera and presented a more ‘slutty’ aspect of her personality. (Successfully so, by the way.) Here she sings “Der Tod will mir als Freund erscheinen” in a way that is to die for (no pun intended). But she is never – ever! – a naughty housewife like Lise Tautin was when Offenbach brought Orphée to Vienna in 1861. We are, after all, in highly conservative post-war times in Germany. If there was any naughtiness, it happened behind drawn curtains. Certainly not in an operetta recording studio.

The cover of the 1968 recording of “Lulu” from the Hamburg State Opera. (EMI)

And then there is Max Hansen, someone who started his career in the sexually liberated Weimar Republic and who was once famous for his suggestive singing of suggestive pre-war lyrics. He’s also the only non-opera singer in the cast, someone who comes from the ‘real’ operetta tradition, someone for whom famous operetta composers actually wrote roles, someone has was part of the bubbly multi-facetted operetta scene that the Nazis killed after 1933. And that never came back!

Hearing Hansen as an older man with an older voice – that offers no ‘nobility’ like many of the other singers on this album – is a wonder. It’s also wonderful. He stands out from the crowd because he never sings notes-as-written-in-the-score, instead he bounces through the music with enormous liberty, phrasing the text for maximum effect, always looking for a joke to play, never ever singing out high notes but instead only tipping at them, or just talking his way through the bits that don’t suit him in terms of range. The result? He’s the only fully ‘alive’ character in this show, and he’s simply stunning as Jupiter.

Of course, Eurydice and Jupiter have one number together, the famous ‘Fly Duet’ in which Jupiter turns himself into a fly to seduce Eurydice in her bedroom with his ‘humming.’ Hearing Rothenberger and Hansen in this together is a landmark moment, in every way. Even Paul Burkhard takes the energy level of his conducting up three notches for this.

The contrast of Rothenberger’s glorious vocals and expansive range (with many inserted high notes she later left out when she recorded the role again) and Hansen’s vaudeville approach to this bedroom number is hilarious. You actually ‘get’ the joke of Eurydice whispering “Und sie summst so schön” – which literally means the fly ‘hums’ so nicely, but can easily be misheard as “Und sie bummst so schön” which translates as ‘and she fucks so well.’ Nestroy knew how to translate Offenbach adequately.

The opening of Offenbach’s “Fliegenduett” from “Orpheus in der Unterwelt.”

It’s 5’38 minutes of operetta heaven. And I found this recording again while cleaning the house for Christmas. Of course, you can listen to Orpheus in der Unterwelt all year round, but this Walhall Eternity Series album is also a great companion for the end of the year: a year that has brought so many outstanding new operetta approaches and so many new operetta talents. They have all come a far way from this 1958 recording in terms of style. Far more ‘chaotic’ and ‘vulgar’ and ‘low region’ than Paul Burkhard or the NDR would have ever dared. Sadly, none of these new operetta heroes have recorded an Orphée aux enfers yet. Before they do, they should certainly listen to Max Hansen as Jupiter.

Considering that there are hardly any post-war documents of Hansen, this is a singular treat. And if you only know the later Rothenberger recordings on EMI, then hearing her here is also a treat. And it’s very (very!) different to her TV version with Hermann Prey where you see – and hear – everything that went wrong with operetta in the 1960s and 70s, after so much had already gone wrong in the 1940s and 50s. It’s a nightmare performance.

So: better stick to Hansen/Rothenberger in 1958 and enjoy! And if you wish to read more about the original glories of Offenbach-in-Vienna, try Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters. It’s a superb read, much better than the recent “Offenbach in Wien” special of the Österreichische Musikzeitung (ÖMZ) which had little new things to say that weren’t better said in the 1999 book.