Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

23 February, 2019

Tea might be the only simple pleasure left to us, as Oscar Wilde once remarked. But you need to be careful who you have it with; because simple pleasures can turn into great discoveries. This week I had tea with singer/researcher Evelin Förster in Berlin, preparing for a talk we are giving together on 3 March about “entertainment” and the German revolution of 1918/19. While I was sitting in her stylish living room, I noticed two books on the coffee table that were new to me and that took my breath away.

“Oh, Donna Clara… Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco,” edited by Walter Labhart, 2017 (edition clandestin)

One was the 2017 Oh, Donna Clara… Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco, edited by Walter Labhart. It’s a Swiss publication and seems to be the catalogue to an exhibition at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zurich. Their director, Christian Brändle, says in his introduction that Oh, Donna Clara is “a visual discovery.”

That’s putting it mildly. Because what you discover in these 240 pages are sheet music covers from the late 1910s, 1920s, and early 30s.

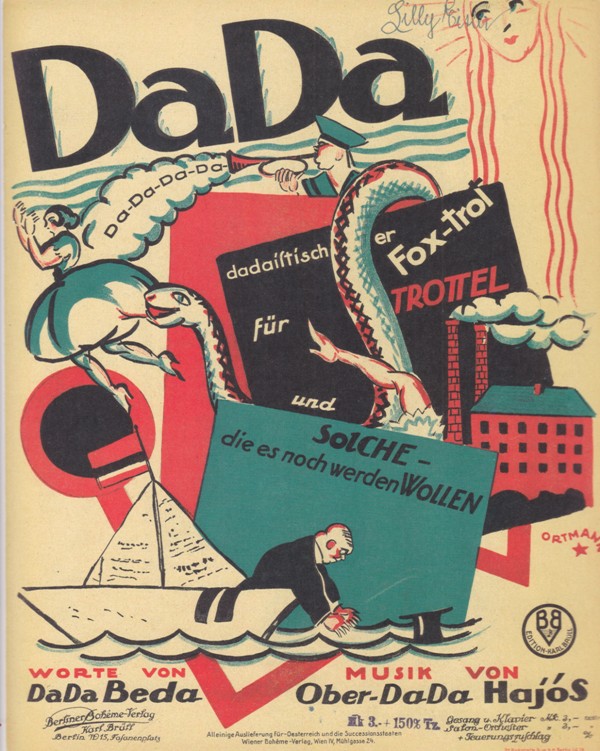

The “foxtrott for idiots” by Fritz Löhner-Beda and Karl Hajós entitled “DaDa.” From “Oh, Donna Clara… Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco,” edited by Walter Labhart, 2017 (edition clandestin)

They are not from one country – so it’s not just the famous German Dadaistic ‘Schlager’ – but examples from all over the world are included, e.g. many French, Italian and Czech song editions. They show that this particular style – the Jazz Age, as you might call it, with all its Shimmies, cakewalks, foxtrots, Charlestons et al – was a global phenomenon. It’s also an artistic phenomenon of great beauty!

A “Black and White” American Cakewalk from 1919, published in Prague. From “Oh, Donna Clara… Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco,” edited by Walter Labhart, 2017 (edition clandestin)

And these sheet music covers reflect the social change and new ideals of the time after World War 1. Some of the song covers from 1918/19 are currently included in the exhibition Berlin in der Revolution 1918/19, which was co-curated by Evelin Förster (surprise, surprise!).

The cover of the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919.” (Verlag Kettler)

And these sheet music covers and their relevance for understanding the revolution is the topic of her talk on 3 March. To be exact, her talk is entitled “Die grafisch gestalteten Notentitelblätter: Spiegelbilder der Parallelwelt in der Revolutionszeit,“ or in English: the graphic design of sheet music covers as a mirror of the parallel world during revolutionary times.

In Oh, Donna Clara you get much more than just this brief time frame 1918/19, and as a result a whole world opens up, context is created, developments become visible.

“Ich bin die Marie von der Haller Revue” from 1928. From “Oh, Donna Clara… Musiktitel aus der Zeit des Art Déco,” edited by Walter Labhart, 2017 (edition clandestin)

One of the sheet music covers that enraptured me was Ich bin die Marie von der Haller Revue. It’s a song from the 1928 revue Schön und Schick by Hermann Haller, with a text by Mr. Haller himself: he had also written Der Vetter aus Dingsda for Eduard Künneke in 1920, with the glorious “Batavia Foxtrott” as the herald of a new dawn in operetta land!

Seeing this Ich bin die Marie von der Haller Revue in full color – instead of the black and white version I had known for years – was a revelation. Maybe it’s just the surprise of seeing something so familiar to you in shining red after all this time?

Miss Förster actually owns an original copy, which she showed me. It was like touching history, because the costume seen on the cover is obviously what inspired the Liza Minelli costume for Sally Bowles, that ‘other’ famous show girl from the Roaring Twenties in Berlin. It’s all there: the haircut, the hat, the eye brows, the dress (if you want to call it that).

Since Cabaret was once the movie that started my fascination with the Weimar Republic, and the movie that taught me that there was another side to history in my home town – which I perceived, as a child in the 1970s, as a very dreary and grey place – I felt like I’d come full circle.

Because on 3 March, after Miss Förster, I get to talk about operettas from the 1920s and the new ‘spirit’ they represent for Berlin. A spirit many are only now rediscovering, as Derek Scally recently pointed out in his “Letter from Berlin” for the Irish Times.

The other book that impressed me during our afternoon tea ceremony was – befittingly titled – Berlin as a Cosmopolitan City: Photographs by Willy Römer 1919-1933. It’s edited by Miss Föster’s husband, Dr. Enno Kaufhold, and it’s in English! (Oh, Donna Clara… is in German, English, and French by the way. Three cheers to the Swiss.)

“Berlin as a Cosmopolitan City: Photographs by Willy Römer 1919-1933,” edited by Enno Kaufhold, 2013 (Braus)

The famous images of street photographer Willy Römer are a central part of the Berlin in der Revolution 1918/19 exhibition, they are the counterpoint to Miss Förster’s selection of sheet music covers, showing the fighting and uprising in Berlin between November 1918 and March 1919. At the end of this fighting came the first German Republic, the “Weimar Republic.”

Amazons on horseback in the streets of Berlin, as PR for a new movie in 1927. From “Berlin as a Cosmopolitan City: Photographs by Willy Römer 1919-1933,” edited by Enno Kaufhold, 2013 (Braus)

In the photos included in this large coffee table book there is little to be seen from the entertainment world of those years, it was simply not Mr. Römer’s focus. But his many intimate portraits of life in Berlin – in the poor areas of the North, inside working class apartments, in parks and streets, where children bathe and workers march in protest, and where the Nazis gather their troops – in these portraits you see the ‘other’ side of that world which plays such a central part in Cabaret too, even more so in the Christopher Isherwood Goodbye to Berlin novels.

At the end of the book there is, somewhat surprisingly, an operetta image after all. You see the Nollendorfplatz and its famous theater, where in 1920 the Haller/Künneke Vetter aus Dinsgda premiered. The Römer photo shows the same square and theater in December 1933 with advertisement for Nico Dostal’s new operetta Clivia – starring Lillie Claus as the ‘new’ Gitta Alpar. (Who had fled from the Nazis by then.) And with a score that toned down the jazz excesses of Paul Abraham and made ‘modern’ rhythms palatable for the new regime.

The Theater am Nollendorfplatz at the end of 1933, with advertisement for Nico Dostal’s “Clivia.” From “Berlin as a Cosmopolitan City: Photographs by Willy Römer 1919-1933,” edited by Enno Kaufhold, 2013 (Braus)

In its way, this is a fitting finale to this wonderful compilation of Willy Römer works. It’s also a fitting finale for that operetta era from Berlin that turned from a globally admired (and successful) phenomenon in the 1920s and early 30s (think of White Horse Inn, 1930) to “Operetta Only for the Germans” after 1933. Because none of the shows that came out in Nazi times ever reached an international audience; unless you count Austria in.

(By the way, the film poster you see on the right of the Willy Römer Nollendorfplatz photo is for the French historical movie Violettes impériales, shown here as Die Veilchen der Kaiserin. If you’re a Luis Mariano fan you’ll know how that plays an important role in French operetta history.)

To find out more about the upcoming symposium at the Museum für Fotografie on 3 March, click here.

In 1920 Friedrich Hollaender summed up the events of the revolution 1918/1919 in the song “Fox Macabre.” (Photo from the catalogue “Berlin in der Revolution 1918/1919,” Verlag Kettler / Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

The great catalogue (in German only: let’s not start discussing Berlin’s museums being as international as their visitors) is also available. It includes many sheet music covers from Miss Förster’s collection and some thrilling photos/postcards showing the interior of various entertainment places in Berlin: like the Walhalla-Theater, the Central-Theater, the Palais de Dance at Metropol-Palast and the Großes Schauspielhaus with the entrance to the cabaret Schall und Rauch.

By the way, on 3 March you also get to hear Prof. Alan Lareau from the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh talking about Victor and Friedrich Hollaender and how they put the revolution into music in 1918/19 at Schall und Rauch.

It was Friedrich Hollaender who best summed up the time with his Fox macabre that has the chorus “Berlin, dein Tänzer ist der Tod” – Berlin, your dance partner is death.

Did Hollaender know, back in 1920, how right he was going to be with that statement?

PS: Mr. Kaufhold will also give a talk at the symposium on 3 March, talking about photography.

..und plötzlich tät’ ich nichts lieber als einen Flug nach Berlin zu buchen, zum Symposium und zur Ausstellung zu gehen und im Dussmann besagte Bücher zu kaufen.. Herzliche Grüße!

Odd, that a book and an exhibition devoted to sheet music cover art would not mention the artists’ names. Illustrations by two of the leading German sheet music artists of the time — Wolfgang Ortmann and Willi Herzig — appear in this post. (The former was my grandfather.) For those with an interest in this genre of art, the indispensable resource is the website imagesmusicales, which features the 10,000 or so examples collected by a Belgian couple, Frank and Divine Lateur.