Steven Ledbetter

The Boston Musical Intelligencer

10 February, 2018

A fortunate series of simultaneous anniversaries—the 300th of the founding of New Orleans, the 75th of the New Orleans Opera, and (perhaps most essential) the 150th of the founding of the New Orleans-based McIlhenny Company, manufacturers of Tabasco sauce—made possible a full staging of George W. Chadwick’s “burlesque opera” Tabasco for the first time since its original productions in 1894: one was an amateur production in Boston, the other a well-received professional tour later that year.

Sheet music cover for “Tabasco,” the “Burlesque Opera” of 1894.

On the last weekend of January, the New Orleans Opera mounted this lively operetta under the baton of Paul Mauffray, who has spent a half-dozen years locating the performing materials and preparing them for modern use. Four public performances, as well as a private one for the McIlhenny Company, which underwrote the production, filled Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré with enthusiastic audiences and not a seat left to be had.

The circumstances of the original 1894 production and the later professional tour created issues that necessitated a great deal of research and editorial work long before it was possible to think about finding a cast and a company willing to mount a revival.

The Cadets Production

George W. Chadwick (1854-1931)—then one of Boston’s leading composers as well as a conductor and teacher—was approached during the summer of 1893 by Boston’s First Corps of Cadets (a socially prominent group of young men whose military calling had long since faded). They had previously mounted original works for the musical theater for several years. In 1893 their show, entitled 1492, had a cast consisting entirely of young men (playing both the male and female parts). The purpose of the production was to raise funds for the construction of an Armory; located at the corner of Arlington and Columbus Avenues, the building is now the Castle, affiliated to the present-day Park Plaza Hotel in Boston; it no longer has any military connection. R.A. Barnet (1853-1933), the librettist of 1492, approached Chadwick, who was known to have a sense of humor and to write music, even in a symphony, that “positively winks at you,” to compose a new piece. He had already worked out the plot, but not yet written any of the song lyrics. Chadwick admitted that he had been thinking for some time about the possibility of writing for the theater; Tabasco looked like an excellent opportunity.

Composer George W. Chadwick. (Photo: Archive Steven Ledbetter)

The libretto contained themes characteristic of comic opera of the day: a setting in an exotic foreign country, often in the Near or Middle East; the interaction in parodistic situations of locals with newcomers from Europe or America; a comic song of self-introduction (especially familiar from the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas that were still new and hugely popular); and a variety of musical styles representing the different cultures and showing off the composer’s ability to suggest each one.

Chadwick had already written two small privately performed comic operas: The Peer and the Pauper, to a text by Robert Grant, in 1884, and A Quiet Lodging, to a text by his frequent collaborator, Arlo Bates, a poet, novelist, and professor of English at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 1892. The latter work was performed at the Tavern Club (a Boston institution whose clubhouse still contains a small theater on its top floor, where members and their wives could enjoy these entertainments created for their private entertainment by the leading creative figures of the city). Quite possibly the 1892 performance suggested to Barnet that Chadwick might be open to writing a full-scale comic opera, which was in a medium and style quite different from the symphonic scores and choral works that had begun to create his reputation. There is no record of a performance of The Peer and the Pauper, which may be why Chadwick reused a finale for an extended scene in Tabasco.

While watching the 2018 Tabasco, I was struck by a possibility—as yet only a hypothesis needing further research to see if it can be verified: Between 1890 and 1899, Chadwick served as director of the Springfield (MA) Festival, held annually in May. During the early part of that decade, his assistant conductor, principal cellist, and rehearsal accompanist was Victor Herbert (1859-1924). Both were exceptionally congenial men endowed with a sense of humor. As it happened, Herbert was writing his very first operetta, Prince Ananias, for the famous theatrical troupe The Bostonians, at the time Chadwick agreed to compose Tabasco. I can’t help wondering if there was not an element of friendly competition between them. (Neither operetta lasted beyond its original production, but of course Herbert’s career continued strongly in the direction of the musical stage; he eventually composed nearly 50 produced operettas. With a few exceptions, Chadwick returned to the concert hall. His future dramatic works were altogether more serious. The principal reason why he dropped the lighter musical theater is suggested below.

A scene from the 1894 “Tabasco” production.

The Cadets’ production of Tabasco opened at Boston’s Tremont Theater on January 29, 1894. A review in the Boston Evening Transcript the next day reported that the large audience was “interested, sympathetic, and generous in its expressions of satisfaction.” It is, of course, worth pointing out that the audience would have contained a large percentage of friends and relatives of the performers, which explains in part why “a big majority of the songs and dances were repeated to appease the calls from over the footlights.” Because the production consisted of amateur performers, the anonymous reviewer did not indicate critique individual participants, though he found the book achieved the “happiest results,” while Chadwick’s music—especially in the quality of its orchestration—suggested that if he so desired he might create more work in the light theater to compare with the opéra comique—a typical comment of the day giving works hailing from Europe a higher rating than creations by Americans.

The 1894 Touring Production

The Cadets’ week-long run achieved what was regarded as an astonishing profit of $26,000. It attracted the interest of a popular actor-manager, the comedian Thomas Q. Seabrooke (1860-1913), who arranged with Barnet and Chadwick to adapt the show for his professional company and to perform it in Boston, New York, and perhaps elsewhere. This professional production opened just two months later at the Boston Museum (which was, despite its name, a theater). The Transcript review noted that the work had been considerably adapted “to the improvement of several places,” though the music was largely the same. A review in the American Art Journal published in mid-May commented that “Mr. Chadwick’s music is remarkable, as coming from a composer of the classic school. Whether or not the topical songs are his, the program does not say [they were], but they are very excellent… The dance music has genuine French swing. One march recalls Beethoven’s oriental attempts in the Ruins of Athens. The concerted numbers are fine specimens of harmonic writing, but with a popular trend.”

What happened next is recounted in the memoir that Chadwick wrote for his family (largely during World War I, while his two sons were both overseas). I quote here some passages from this vital document. Chadwick’s relations with Seabrooke explain, to a great degree, why Tabasco disappeared after 1894.

The whole show was conducted by Paul Steindorff, an excellent musician, who worked as hard as he could to make a good show…. Of course many changes had to be made. Seabrooke’s part had to be fattened at any cost. He was really a stupid ass without any natural talent, but had learned a lot of horseplay and silly tricks which he could put over on the average audience.

When the company was ready we moved (including myself) to New London, Ct., where we rehearsed, night and day for three days, finally giving the first performance in Norwich, Ct., on Apr 6, and the next in New London on Apr 7. Neither of which did I hear. We opened in Boston at the old Boston Museum on Apr 9 to a very swell and enthusiastic audience, and the 2d night the Cadets attended in a body. But after a week or two the houses began to drop off and we moved to N.Y., where we opened in the Broadway Theatre and played until well into the summer.

Up to this time we [Barnet and Chadwick] had managed with some difficulty to collect our royalties… But the next season [in the autumn], when [Seabrooke] traveled all over the west, we began to have trouble at once. At first we got a few straggling checks, but these soon ceased, and we found that we were practically helpless unless we sent a man to stay with the company and watch the box office. Of course it did not pay to do that, so we let it go.

But later on, when Seabrooke came back to Boston, we put him in jail, where he languished for a short time…

And so I got my experience in writing & working for the stage, and it has been of great value to me—probably more than the money would have been.

It seemed a pity to waste practically a whole year’s time on such unworthy stuff, but I have never regretted it. After all, lessons in human nature are expensive, but they are worth the money!

Before starting on the road, Seabrooke wrote the McIlhenny Company to get their blessing for using the name of their hot sauce (a registered trademark) both in the title of the show and as a main plot element. The company was happy to agree, and even developed a souvenir offering to be handed out at performances: a miniature reproduction of the full-sized bottle containing 1/8 oz. of the spicy item. They have continued to make the miniature bottle to this day, and repeated the gesture in New Orleans in January, with a large bowl of sample miniatures at each entrance to the theater.)

Seabrooke’s tour in the fall of 1894—covered most major towns in New England, then proceeded southward from New York along the Atlantic coast, west to New Orleans, continuing as far as Texas, then northward in the general direction of Chicago, which it never reached. The total number of cities in which Tabasco played was 49. As often happens with a touring production, changes were made on the road without the authorization of the composer, and the performing materials became worn and used. This explains some of the difficulties in creating a version of the show for a modern performance.

Chadwick’s phrase “unworthy stuff” was surely made in comparison to another work that he finished while composing Tabasco: his Third Symphony, which received a national award as the most important American symphony. The telegram announcing this honor came from none other than Dvořák, who was then living in New York. This signal success in the symphonic line might well have affected Chadwick’s decision not to undertake further work in the light musical theater. Since Chadwick evidently traveled with Seabrooke’s company at least until the show’s opening in New York, I can’t help wondering whether Dvořák might have joined him at an early performance. But in less than three years, Chadwick had been named director of the New England Conservatory, a position of such social and cultural elevation that he probably could not even think of pursuing light opera again.

Rediscovering and Rebuilding the Performance Materials

After putting an end to Seabrooke’s performances, Chadwick retrieved his autograph full score and orchestral parts. These he packed into a cardboard box that went into his basement, essentially forgotten. After his death, when the family divided his musical estate—at least, its “important” parts—between the New England Conservatory and the Library of Congress, most of the Tabasco materials remained in storage with the family. (While cataloguing the materials at NEC in the late 1970s, I found only a few fragmentary orchestral parts; the rest, I assumed, was lost.)

The arduous task of locating and editing the dispersed performance materials is due to the patient investigative and musical work of conductor Paul Mauffray, who persuaded the New Orleans Opera to mount the piece and conducted the performance. Mauffray is a native of New Orleans with extensive experience in the field of opera. He studied at Louisiana State University and Indiana University. He has had a long connection with Czech music, shaped by his deep interest in the operas of Janáček. He lived in the Czech Republic, working as assistant to Bohumil Gregor, Jiří Bělohlàvek, and Sir Charles Mackerras in performances of Janàček’s major operas. He has returned regularly to work with the Prague and Slovak Orchestras. He lived in Brno for five years until 2009, undertaking graduate musicological study at Masaryk University in the manuscripts of Janáček. And he maintains a regular connection with the Hradec Králové Philharmonic, with which he led a concert performance of Tabasco in 2015. (That performance can be heard on YouTube, to which I have linked several numbers, below.)

The first production of “The Burlesque Opera of Tabasco” was praised for the shaven legs of the cadets playing harem girls.

In his home town he was looking into the 300-year history of the New Orleans Opera, with special attention to what was happening in the Crescent City in the 19th century, during the decades before the development of jazz, and pursuing the long history of opera there. Running across a reference to an American opera in 1894 with the unlikely title Tabasco intrigued him. At the time he did not know that the sauce of that name had already existed for nearly a quarter of a century.

He began to look into the possibility of finding the musical materials. There was a piano-vocal score issued by the Boston publisher B.F. Wood in time for sale to members of the audience at the Cadets’ production. A reprinting came forth in connection with Seabrooke’s tour—but it was in fact identical to the first edition, despite the fact that many changes had been made for the tour version, none of them reflected in the vocal score.

The breakthrough came in 2012 when he learned that the Chadwick family still had a cardboard box full of Tabasco material in their basement (it has since been deposited, along with other remaining elements of Chadwick’s life and work, in the library and archive of the New England Conservatory). With these materials, and others, more scattered, Mauffray was confronted with three different versions of the libretto, a full score that was nearly complete, problematic orchestral parts, excerpts in piano score, and other miscellaneous materials. There were handwritten annotations on the available manuscripts whose purpose was not always clear. They might have been added during rehearsals for one production or the other, or they might have reflected changes found to be necessary on the road, or for some other reason. It was also clear that the printed vocal score was intended to provide only the songs, which might be played on the piano in the purchaser’s home. The overture was omitted, as well as a number of connecting orchestral passages necessary in the theater.

A workable libretto was essential. The second libretto most clearly reflected the professional touring version, which, since it was intended for a cast with actors of both sexes, was the one most useful for developing the score for a revival today. Even so, it needed a certain amount of rewriting to deal with jokes that were entirely too ancient to be understood today, not to mention a number of references to Islam and Islamic personages that were characteristic of the humor of the day in Europe and the United States, but might prove offensive today. These were adjusted by the stage director Josh Shaw. He supplied added lyrics in situations where a song had only one stanza, insufficient for it to make a strong impression in the show; such was especially the case with stylizations of French, Irish, Spanish, and American (southern) musical styles in a kind of dream sequence in the second act.

The full score seems to have been written out by Chadwick himself (though his family memoir mentions one song apparently orchestrated by an assistant under his direction). There were places where brief passages needed to be added because annotations mentioned links of eight bars or so, which were not to be found. And in one song (the lament of the Irish cook), a note in the score indicated that an offstage chorus was to sing a well-known Irish song, “The harp that once through Tara’s halls”—but there was no music for this addition. For this passage, Mauffray created the four-part mixed chorus music that was required.

One major surprise was the inclusion of a song by Ludwig Englander (1853-1914), born in Vienna, who came to America in 1882 to become a conductor at the German-language Thalia Theater in New York. He began to write shows regularly after 1894, the year of his greatest success, The Passing Show. It is not clear why Seabrooke went to Englander if he felt the need for a new song, since Chadwick was still involved, at least until the beginning of the run. The wordless sheet music was labeled “Act 1 #2 Lola’s song.” Lola was played by Elvia Crox, soon to be Seabrooke’s wife, who otherwise had only a few bars to sing during ensembles. Frederic Kroll provided the lyrics about “The raging wave,” which she and her brother Marco have just passed safely in coming to Tangiers. One possible explanation for the interpolation is that the lady may have already sung it in another show, so it was an easy choice to adapt it with new words. This kind of interpolation was a frequent practice in the musical theater of the day, without regard to the feelings of the main composer.

This long and careful study of the musical source materials and such information as could be gleaned from newspaper accounts, correspondence, and so on, made possible the lively and delightful production put on by the New Orleans Opera in January as part of its 75th anniversary.

Tabasco in the New Orleans Opera Production

The decision of New Orleans Opera to include Tabasco in its 75th season was certainly a welcome one to me. Having studied Chadwick’s life and music since preparing and conducting a performance of his lyric drama Judith at Dartmouth College in the 1976-77 academic year as a contribution to the American Bicentennial, I wanted to hear as much more of his music as possible, In the intervening 40 years, a remarkable amount of it has been performed and recorded, including two of his three symphonies, many other overtures and tone poems, his verismo opera The Padrone, which was never performed in his lifetime (perhaps the greatest professional disappointment of his life), all the string quartets and the piano quintet, and many smaller works for piano solo or voice and piano. But Tabasco is a work that I never expected to hear, and even less expected to see. Anyone with an interest in the American musical theater owes a real debt of gratitude to Paul Mauffray for pursuing the performing materials, undertaking the detailed research to put them in performable shape, and seeing to it that they actually reached performance.

Poster for George W. Chadwick’s “Tabasco” in 2018.

The production was colorful, handsome, and lively. Stage director Josh Shaw kept things moving with energetic role-playing by the entire company, and the four dancers from the New Orleans Ballet Theatre (Liza Keller, Felicia McPhee, Shayna Skal, and Hannah Whelton, choreographed by Amy Lawrence, lent a sylphlike air to the proceedings, especially amusing in a dream dance in which they passionately carried jeroboam-sized bottles of Tabasco sauce. The set, designed by George Johnson, made effective use of the small theater’s stage (reshaped from scene to scene by round cushioned seats on rollers, and a ship’s gangplank that occasionally lowered from the wings to allow entrances from a steamship delivering characters from the Mediterranean). Julie Winn’s costumers cast a panoply of lush colors onto the stage, made the more brilliant by Mandi Wood’s lighting design.

Musically, the entire show was delightful. The 30-piece orchestra, consisting of members of the Louisiana Philharmonic, played excellently in a score that was laid out exactly like those of the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. This is hardly surprising, because those shows were in fact still being created at the time, and they had become the most popular works in the musical theater in America for fifteen years. Chadwick used Sullivan’s instrumentation of two flutes, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, pairs of horns, trumpets and trombones [Chadwick used only one], percussion (two players), and strings. Conductor Paul Mauffray directed everything with elan, shaping the singing and the playing with just the right pacing for both the comic and the sentimental numbers from the lively overture (here) to the finale.

In the following description, the links lead to the 2015 concert performance that Paul Mauffray conducted in 2015 with the Hradec Králové Philharmonic. The availability of this performance allows anyone to hear this long-forgotten music, but the performers are neither the orchestra nor the singers whom I heard in New Orleans.

The principal characters played their delightfully unlikely parts with verve and fine singing. The ship’s captain Marco and his sister Lola (Jonathan Tetelman and Brindley McWhorter) are both willing to enjoy a flirtation while in this exotic country. Marco sets the plot off by carrying a little bottle of a red-hot sauce among his wares to trade. The Grand Vizier (Ivan Griffin) is not unlike Gilbert’s Mikado in that he loves the thought of carrying out bloodthirsty execution and laments the fact that there are few opportunities for them these days. Generally unhappy with the current situation in Tangiers, he is planning the overthrow of the Pasha (also called the Bey, Hot-Hedem) with Hasbeena (Daveda Karanas), once the number one member of the Pasha’s harem, but now cast aside. Both of them sing entrance songs that tell us who they are—the Grand Vizier’s “But not to me” (which can be heard here in the Czech concert performance: here) and Hasbeena’s “It’s hard for an old concubine.”

In order to keep the Bey from learning of their plot, they find a new “French” chef to replace one who was summarily executed for not providing spicy enough food to meet the ruler’s taste. Given the dangers of the job, it is not easy to find a candidate. But an Irishman, Dennis O’Grady, is pressed into service, calling himself François (Taylor Miller). He is confident that he will satisfy the Bey as long as he speaks as much French as he is capable of (“Oh, I’m a chef of high degree”- here). When the Bey (Kenneth Weber) arrives with his own entrance song, “I do not care what other people say,” (here), he gets a letter informing him that he is about to receive a new addition to his harem, a gift from the Bey of Morocco. Meanwhile he eagerly samples the luncheon that “François” offers, but it proves far too bland. If François cannot do much better by dinnertime, his head will roll.

Scene from the 1894 production of “Tabasco.”

The new harem girl, Fatima (Betsy Uschkrat), arrives, lamenting her fate (following a dramatic recitative, she recalls her native land: “O lovely home” – here). François fears the worst with the dinner he has been charged to make and laments ever having left his native Ireland (“The shamrock blooms white” – (François’s Lament – here).

When Marco catches sight of Fatima, he is smitten at once. He wants to escape with her on his ship, and she has no desire to join the harem. In order to avoid detection, they plan to knock François out with a blow to the head and dress him in the covering veils of the harem women to pass him off as Fatima, then present him to the Bey while they are disguised as harem guards. The presentation goes awry (“Gem of the Orient” – here) when they Bey wishes to kiss her. Marco and Lola are found out; Fatima introduces herself as the new harem girl (enchanting the Bey) and interrupts the execution, claiming Marco as her cousin and Lola as her sister. But now the Bey is thinking of dinner, and he demands the François produce the appropriately spicy meal. Lola saves the day; she passes Marco’s bottle of Tabasco to Francois; he liberally shakes over the viands. The Bey declares it to be the best thing he has ever eaten and dubs Francois “the Peer of Tabasco.”

The Interlude between the acts takes up the more romantic and sentimental side of the piece (here).

In Act II, Francois is riding high in the Bey’s esteem, but he worries that the bottle of Tabasco will soon be exhausted because of the Bey’s passion for it. Fatima and Marco express their love (“My heart again to hope begins”—here) but this does not solve their problem of how to escape Tangiers and where to go. The plotters daydream of various possible refuges: Spain, Ireland, France, and–Kentucky! Each of these is represented in a characteristic song which has nothing to do with the plot, but provides opportunities for melody and dance: a bolero, “In Barcelona lived a maid” – (here); an Irish ditty, “Ah now thin be aisy for love is a daisy” (here); a French rigaudon (“He met his love at the students’ ball” (here); and, finally, a plantation song, a pastiche of Stephen Foster style (here).

“The March of the Pasha’s Guard” was so successful that Chadwick sold it to B.F. Wood for a separate publication and claimed to have sold 100,000 copies. In the operetta, of course, it provides an opportunity for some lively and comic “military” maneuvers (here); this was the great age of march composition and professional bands (Sousa’s was only the most famous). When the lovers try again to disguise themselves as members of the harem in an attempt to sneak away to Marco’s ship, they are caught out in the delicate Dance of the Harem. (here) for their terpsichorean incompetence. The arrival of a ship motivates a rousing sea song for Marco and the men’s chorus (“Ho, mariner, ho!” – here); it signals the arrival of a ship that might provide escape. All is set right when the assassination plot against the Bey is foiled and the ship is discovered to carry a cargo entirely of cases of Tabasco sauce to guarantee the Bey’s future gastronomic happiness.

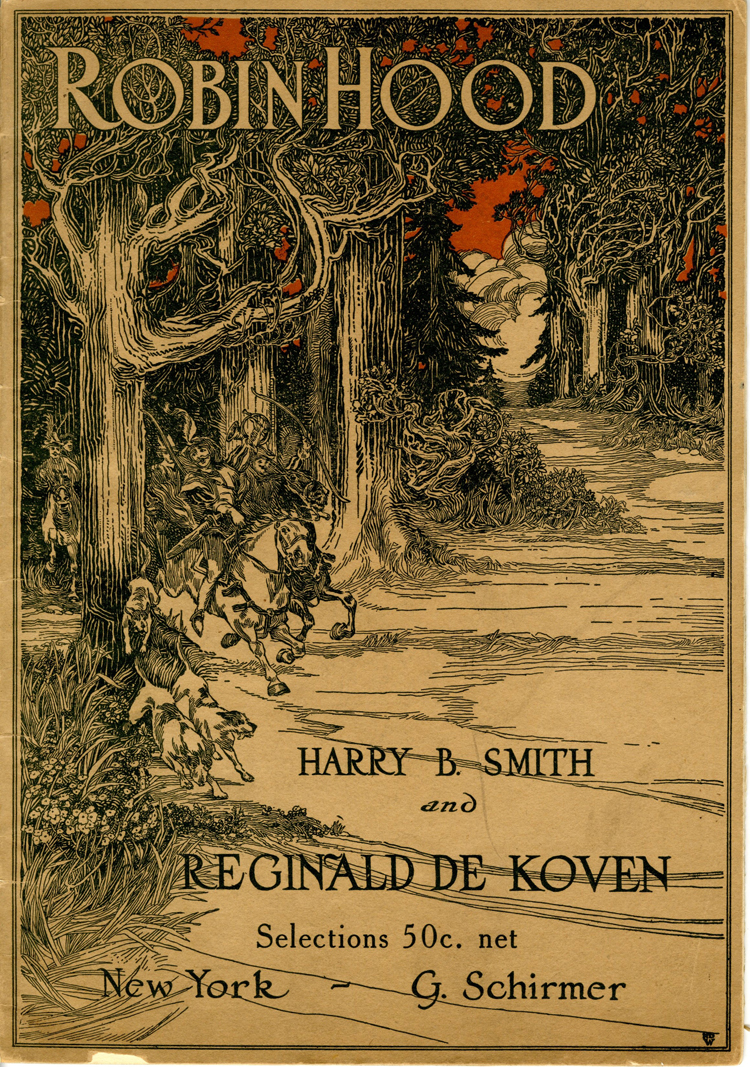

Few operettas of the 1890s or beyond enjoyed a completely consistent libretto. Certainly the most unfailingly (and amusingly) logical were those showing the topsy-turvy logic of W.S. Gilbert. Many were their imitators, but most of them found easy solutions to plot problems. Still, despite its strong period flavor, Tabasco stands up quite well against many other American shows of the day, including the early shows of Victor Herbert and Reginald DeKoven’s Robin Hood. It is Paul Mauffray’s dream to perform Tabasco again in each of the cities that Seabrooke visited in his original tour, or at least those that have an opera company that might sponsor the show.

Selections from “Robin Hood,” published by G. Schirmer, 1891.

Hearing Tabasco, and, better yet, seeing it, brings out more strongly than ever that element of Chadwick’s musical style that was willing to be playful, to be, in that regard, “American,” in short, to use his own laudatory phrase about composers who did this—to “write himself down,” to be in his music exactly who he was.

And for experiencing this aspect of Chadwick’s music—and to have a wonderfully good time of it, too—warm thanks are due to Paul Mauffray and the New Orleans Opera for a truly unexpected treat.

Steven Ledbetter is a free-lance writer and lecturer on music. He got his BA from Pomona College and PhD from NYU in Musicology. He taught at Dartmouth College in the 1970s, then became program annotator at the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1979 to 1997.

To read the original article, click here.