Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

One of the most successful of extravagantly humorous full-length opéras-bouffes written and composed by the playwright/composer Hervé, Chilpéric went even further in its almost surreal burlesque humour than Meilhac and Halévy had done with their recent texts for Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène, Barbe-bleue or La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein. Hervé went back to the medieval era, so successfully used by Offenbach and Tréfeu in Geneviève de Brabant, for his subject matter, and he alighted on the Merovingian King Chilpéric I of Neustria and Soissons, whose lastingest claim to fame (apart from this opéra-bouffe) seems to have been that he was the first monarch to construct a circus in Paris. Chilpéric’s life and career were decorated with murderous women. His second wife, Galswinthe, was murdered by Frédégonde, who became his third wife, and who subsequently came to clutches with Galswinthe’s sister, Brunehaut. All these dangerous ladies turned up in Hervé’s opéra-bouffe.

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting of Marcelle Lender doing the bolero in “Chilperic”, 1895.

Frédégonde (Blanche d’Antigny, a late replacement for Oeil crevé star Julia Baron) starts the evening as an innocent little shepherdess, but she is spotted during the course of a hunt by the randy king (Hervé) and whisked off to court to be royal laundress etcetera. No one else is very pleased, not Frédégonde’s peasant swain, Landry, nor Chilpéric’s brother Sigebert (Berret), nor especially his brother’s Spanish wife Brunehaut (Caroline Jullien), who had lined up her sister Galswinthe (Mlle Berthal) as a wife for the King, intending then to assassinate the royal couple and claim the throne herself by kinship. Since this Spanish marriage brings advantages of state, however, it is still on, and when it becomes imminent Chilpéric has to get rid of the slightly used Frédégonde. But Frédégonde has shown remarkable powers of adaptation in her swift transformation from shepherdess to royal plaything, and she doesn’t let herself be evicted quietly. She screams, howls, and sings embarrassing top Cs all round the throne room. And now the murdering starts. Brunehaut has seduced Landry and persuaded him to kill Frédégonde, Frédégonde has attracted the court chamberlain, Le Grand Legendaire, and has asked him nicely to strangle Galswinthe on her wedding night, whilst Chilpéric has become deeply suspicious of Brunehaut’s machinations and ordered the court doctor (Milher) to slip her something poisonous. Everything comes to a peak in the nuptial chamber on the royal wedding night, when the King has slipped out for a bit to defend his city against an irritatingly untimely attack by a disloyal brother. The three would-be murderers attack, the three women fight back, and in the dark it all gets very confused before someone presses a button which sends the whole lot of them — and the bed — straight down to the dungeons. Chilpéric wins his little battle, pops back home and sorts everyone out in time for a jolly finale with no deaths and only a little bit of stripping and whipping.

Hervé’s lively score was as full of fun as his libretto, with Frédégonde being particularly well provided with an introductory waltz (`Voyez cette figure’), the pyrotechnic musical tantrums on her dismissal from court, and a lament in burlesque of the grand operatic (`Nuit fortunée’), whilst Chilpéric scored with his entrance number, the nonsensical Chanson du jambon, sung perched unhappily on the back of a real, live horse like the ones they use at the Opéra, and with his second-act butterfly song (`Petit papillon, bleu volage’). Galswinthe’s boléro (`À la Sierra Morena’) added a touch of the Spanish, whilst a basso druid (Varlet) opened proceedings Norma-like, invoking `Prêtres D’Ésus’.

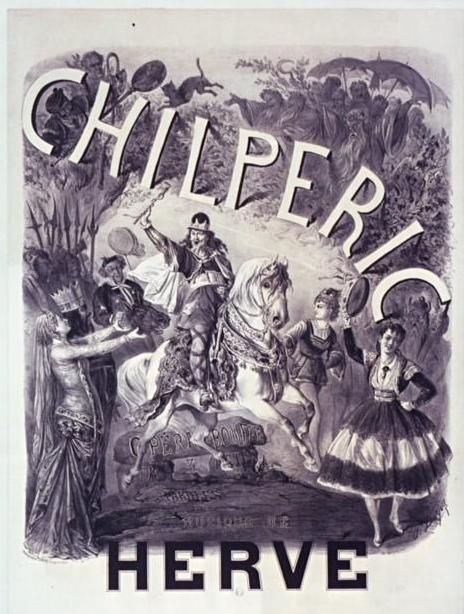

Cover of the piano score for “Chilpéric”.

The Folies-Dramatiques production was a fine success, running for more than a hundred nights, and Chilpéric was soon gratified by Christmas-tide burlesques of its burlesque. Hervé’s music was borrowed to decorate the Eldorado’s Chilméric (10 December 1868), whilst the Alcazar made a double shot, combining both the season’s big hits in the title of its revue Chilpéricholle (31 December 1868). At the same time the show began to be seen in other countries. America was apparently the first, getting a taste of the original French version when Joseph Grau’s opéra-bouffe troupe introduced the show with Carrier (Chilpéric), Rose Bell (Frédégonde), Marie Desclauzas (Galswinthe) and Mlle Rizarelli playing Landry in travesty at the head of the cast. The current craze for French opéra-bouffe meant it had much competition and, since Grau held the season’s megahit Geneviève de Brabant in his repertoire, Chilpéric was played only irregularly, though not without success, as a supporting piece to Offenbach and Tréfeu’s hit. An English-language version was seen later, in 1874, when Emily Soldene visited America and herself took the rôle of the comical king alongside Agnes Lyndhurst and Lizzie Robson.

Soldene had already appeared as Chilpéric in London, when she had deputized for the composer-star in Richard Mansell’s production (ad Mansell, Robert Reece, F A Marshall) at the Lyceum. London’s Chilpéric was probably the most successful staging of the show anywhere. Hervé repeated his Paris performance alongside soprano Emily Muir (Frédégonde) and the young Selina Dolaro (Galswinthe), and the show caused a real sensation, giving a huge boost to the budding craze for opéra-bouffe in Britain. It ran from 22 January to 9 April, being taken off only to allow the composer’s Le Petit Faust to be given its share of the season’s time. The following year Soldene, who had in between times toured the piece in the British provinces, brought a version back to London (Philharmonic Theatre 9 October), playing her version concurrently with another production mounted by John Elliot Mallandaine at the Royalty Theatre (28 September). In 1872 the Folies-Dramatiques company visited London to play the show in French (Globe Theatre 3 June), with Luce as the King and Mlles d’Antigny and Jullien and Milher all in their original rôles and in 1875 (10 May) the Alhambra gave Chilpéric an extravagant new mounting with Charles Lyall (Chilpéric), Lennox Grey (Frédégonde), Kate Munroe (Galswinthe), Adelaide Newton (Landry), Harry Paulton (Dr Ricin) and Emma Chambers (Brunehaut) featured, a production which ran for three months. A fresh English version (ad Henry Hersee, H B Farnie) was produced at the new Empire Theatre in 1884 (17 April) with Herbert Standing, Camille d’Arville and Madge Shirley in the leading rôles, capping a British career for Chilpéric which was only bested by a handful of opéras-bouffes.

In America, the pieces was given a further brief showing at New York’s Robinson Hall (19 July 1875) with ex-Soldene tenor Henri Laurent as the King, and Pauline Markham, ex- of Lydia Thompson’s blondes toured what claimed to be a version of Chilpéric in her repertoire in the late 1870s.

And Broadway saw the piece again briefly in 1879 when a Mdlle Ninon Duclos appeared in an uncredited, unappreciated and mutilated version of Chilpéric at Tony Pastor’s (7 May) which was quickly withdrawn.

Australia followed quickly where London led — although W S Lyster felt obliged to add a subtitle `the King of the Gauls’ to help antipodeans likely to be bemused by the show’s unfamiliar name — with a production featuring Henry Bracy as the said King. Local burlesque queen Lydia Howard subsequently toured a highly approximate version decorated with more extraneous music than original Hervé, and Australia and New Zealand got the ionternational article in 1877-8 when Soldene appeared around both countries in what was announced as `her original rôle’.

In 1872 the Folies-Dramatiques remounted Chilpéric with Hervé supplying two new songs, a romance for Siegebert and a solo for Alfred, the principal page, and in 1876 Paris saw a further reprise of the show with Hervé again in his original rôle (Théâtre des Menus-Plaisirs, October). In 1895 the Théâtre des Variétés mounted a new production, the libretto now reorganized into three acts by Paul Ferrier, and with a cast headed by Albert Brasseur (Chilpéric), Marguerite Ugalde (Frédégonde) and Marcelle Lender (Galswinthe), Baron as the doctor and Vauthier as Siegebert, and the quarter-of-a-century old piece found itself a renewed popularity which led it to both a straight run of over 100 nights and, this time, to a production in the German language. Eduard Jacobson and Wilhelm Mannstädt’s König Chilperich was seen at Berlin’s Theater Unter den Linden later the same year, with Alexander Klein and Frln Fischer in the lead rôles, with sufficient success for it to be brought back again in the new year. The Vienna Carltheater staged the same version 11 months later with Julius Spielmann playing Chilpéric, Betty Stojan as Frédégonde and Ernst Tautenhayn as Landry. It was played some 25 times.

The passing out of favour — and of comprehension — of the more extreme style of burlesque in the 20th century has led Chilpéric to disappear from the repertoire since.

USA: Theatre Français (Fr) 1 June 1869, Lyceum Theater (Eng) 9 December 1874; UK: Lyceum Theatre 22 January 1870; Australia: Prince of Wales Theatre, Melbourne Chilpéric, the King of the Gauls 25 July 1874; Germany: Theater Unter den Linden König Chilperich 21 December 1895; Austria: Carltheater König Chilperich 28 November 1896

Thanks a lot! I have seen some extracts from the Angers opera production but where can I see the rest of it? It looks great fun!