Ignacio Jassa Haro

Operetta Research Center

25 April, 2022

Here’s great news: a new book on Offenbach is out! It is entitled Offenbach, Composer of Zarzuelas and has been published in Spain. But how can its title unite the name of the famous Franco-German composer with that of the quintessentially Hispanic musical theatre genre known as zarzuela? Is it a book about the creator of the operetta and the kind of musical theatre he brought into vogue, or is it instead dedicated to Spanish zarzuela?

Enrique Mejías García’s “Offenbach, compositor de zarzuelas.” (Photo: Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales)

These and other questions of this nature, posed from the very beginning – as the provocative title of this publication indicates – are the driving force behind the literary-academic work of its author, the musicographer and musicologist Enrique Mejías García. Enrique is a person with whom I have a very close friendship of many years, so this here is not an impartial academic review; on the contrary. Instead, my words aspire to be an impassioned taking-of-sides to encourage those who read this to run and get hold of this publishing treasure.

Enrique Mejías García enjoys, despite his youth, a fertile musicographic career which has allowed him to put on record some of the aspects of his musical thinking which later served as the ideological foundations for the formulation of his doctoral thesis, the germ of this volume. His starting point was a critical review of what Spanish musical historiography had understood by zarzuela over time, an almost monolithic interpretation since the genre’s birth in the mid-nineteenth century until the beginning of the twenty-first, and formulated from the assumptions of national exceptionality.

Enrique Mejías García

from the Centro de Documentación y Archivo (CEDOA) de la SGAE. (Photo: Private)

During this long century and a half zarzuela was understood as a kind of creative path that should lead to the full establishment of Spanish opera, that great utopia rarely achieved in Spanish musical culture. Thus, as the genre moved away from the ideal of high culture, the musical intelligentsia lowered their appreciation of its aesthetic qualities. Precisely what Enrique proposes is to understand this move away from opera not as a decadent deviation but as a conscious choice to place itself in a completely different sphere from that of opera: that of popular musical theatre or operetta.

So this book is an essay on zarzuela as operetta, or in other words a book about operetta. But why on earth does it have Offenbach’s name in its title, and is it aimed at those interested in the Cologne-born composer, or will they be disappointed in their expectations? It is definitely also a book about Offenbach. This composer is the ideal tool to demonstrate the author’s thesis because his works, when adapted in Spain – and not infrequently, more or less half of his corpus of musical theatre, was adapted into Spanish – were converted into zarzuelas by the authors of this genre and performed by the same impresarios and performers. This conversion did not really imply a change of genre; Les brigands in its original French version or in its Viennese adaptation Die Banditen was just as much an operetta as in its zarzuela form Los brigantes.

![Dolores Franco de Salas as Fragoletto in "Los brigantes," around 1875, Teatro Español, Barcelona. (Photo: [Esplugas], Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques, Barcelona)](http://operetta-research-center.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/1.jpg)

Dolores Franco de Salas as Fragoletto in “Los brigantes,” around 1875, Teatro Español, Barcelona. (Photo: [Esplugas], Centre de Documentació i Museu de les Arts Escèniques, Barcelona)

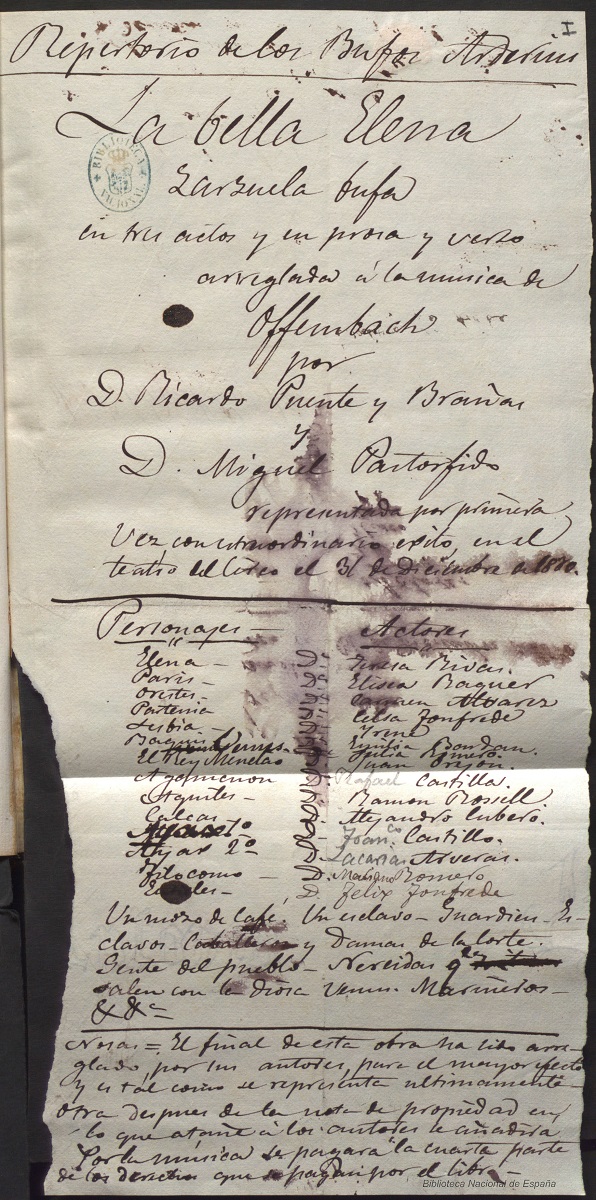

Title page (with cast) of the manuscript libretto of “La bella Elena,” one of the two Spanish adaptations of “La belle Hélène.” Madrid, 1870 (Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de España)

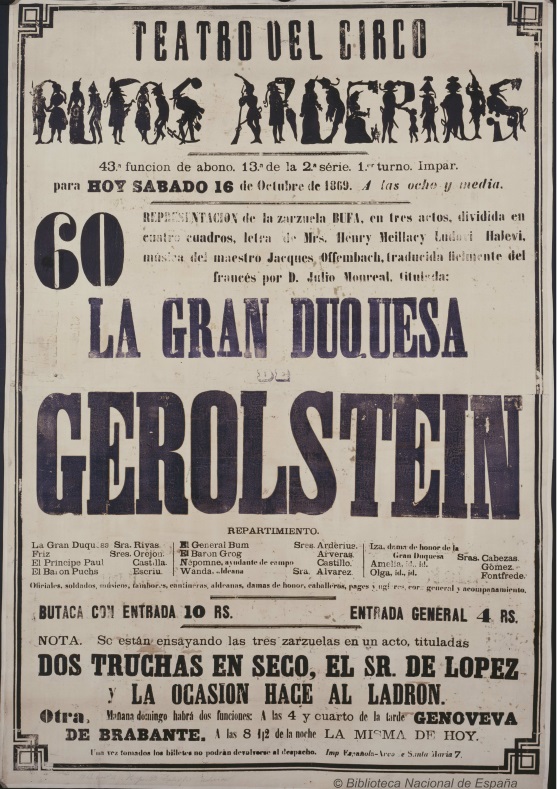

Mejías’s knowledge of Offenbach is as competent as his knowledge of Spanish musical theatre. In this respect it should be noted that the book benefits from Enrique’s experience as a genuine catalyst for projects to revive Offenbach’s works in Spain, such as the Teatro de la Zarzuela’s celebrated production of La Gran Duquesa de Gerolstein or the Fundación Juan March’s El caballero feudal (Croquefer), the latter as part of the wider concert series “Offenbach, Composer of Zarzuelas”, which also benefited from his scientific tutelage.

The book is structured via chapters that function as case studies, following the model of Camille Critenden’s famous monograph on Johann Strauss and Vienna, as the author himself acknowledges in his introduction. This development gives the text enormous amenity, turning it into a collection of essays contrasting in style and subject matter, yet united by a powerful common thread, by constant cross-referencing and by a powerful narrative vigour. These chapters are arranged in three parts, corresponding to three different moments in Spain’s political history during the second half of the 19th century: the reign of Isabella II, the revolutionary period following her dethronement, and the Bourbon restoration. Some of the chapters are practically a book, not so much for their length as for the depth and originality with which they address their subjects. The chapter on Italian operetta companies and their impact on the Spanish stage, which could be considered a pioneer in addressing these issues, or the chapter on Jacques Offenbach’s exciting stay in Madrid in 1870, fleeing the Franco-Prussian war, would be two good examples of books within the book.

María Palou as Marieta, protagonist of “La diva,” circa 1906. (Photo: Kaulak, Collection of Ignacio Jassa Haro, Madrid)

The volume also features a meticulous edition. It is preceded by a substantial foreword by Professor Juan José Carreras of the University of Zaragoza, who places the monograph in the context of Offenbachian studies. All the chapters are carefully annotated, so that the reader is not obliged to interrupt the main discourse, while at the same time enriching it, if desired, with the subsequent reading of suggestive footnotes. Also noteworthy is the rich selection of illustrations that punctuate the volume, many of them unpublished; the images selected are absolutely pertinent and fully integrated into the discourse. There are also a few musical quotations necessary to support some of the analyses of the works studied. Special mention should be made of the final appendix, which is extraordinarily meticulous and very detailed, and which brings together the main factual aspects of the reception of Offenbach’s work in Spain. Careful onomastic and title indexes and an analytical bibliography round off a publication that awaits both the amateur reader and the scholar.

Poster for the 60th performance of “La Gran Duquesa de Gerolstein.” Teatro del Circo (Bufos Arderíus), eleven months after its premiere. Madrid, 1869. (Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de España)

There are those who might label Enrique the enfant terrible of Spanish musicology, for his apparent deconstruction of zarzuela. We believe, quite to the contrary, that not only does he not detract one iota of recognition from the Spanish lyric genre par excellence, but he also greatly enriches it by placing it in the place where it always was, even though it was not appreciated there: that of international popular musical theatre, vulgo operetta.

This book and Enrique’s entire career constitute a marvellous love song for zarzuela, broadening its meaning and adding to the recognition of its idiosyncratic traits – so celebrated at home and abroad but at the same time so dangerously endemising – an understanding of its universal nature that restores it to a place in the history of operetta from which it should never have been absent.