Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

27 March, 2020

On a sunny summer afternoon last year I had a long inspiring conversation about Richard Genée (1823-1895) with two operetta enthusiasts. Ever since then I’ve meant to listen to some actual Genée music. It seems such plans sometimes take longer than expected. But with Corona and self-isolation I’ve finally managed to get around to four Genée shows on CD: Der Seekadett (1876), Nanon (1877), and his earlier Der Musikfeind (1862) and Rosita (1864).

Composer and librettist Richard Genée.

Obviously, the author Richard Genée doesn’t need any introduction. He wrote the text books to some of the most famous, successful and beloved Viennese operettas of the 19th century, among them Die Fledermaus, Eine Nacht in Venedig, Der lustige Krieg for Johann Strauss, Boccaccio and Fatinitza for Franz von Suppé, not to mention Gasparone and Bettelstudent for Carl Millöcker, Deutschmeister for Karl Michael Ziehrer. He also translated Offenbach’s Périchole and Fantasio for Vienna, as well as Hervé and Lecocq works. His own compositions, on the other hand, have kind of fallen off the radar. So there might be something to (re)discover, I thought!

In his book Operette von Abraham bis Ziehrer Otto Schneidereit pays detailed attention to Genée with a four-page biographical sketch, and discussing Musikfeind and Nanon. Volker Klotz also gives a vast biographical sketch in his Operette book, and analyses Nanon backwards and forwards, not coming to a positive conclusion though. Other shows, such as Im Wunderland der Pyramiden (1877), Der letzte Mohikaner (1878) and Die Piraten (1886) seem to be little more than titles in history books that beg to be looked at again in our “de-colonize everything” age of critically re-examining the past.

The double disc album of four Genée shows, released by Cantus Classics.

Anyway, as I was recently looking for historic Offenbach recordings from German radio stations, I stumbled upon a double disc that promised “4 legendary recordings” of Genée shows which were made in Hamburg 1955, conducted by Richard Müller-Lampertz (Seekadett and Nanon), as well as a radio recording from Leipzig 1959 (Musikfeind), and another one from Hamburg 1954, but conducted by Wilhelm Stephan (Rosita), the latter a “romantisch-komische Oper” and not an operetta.

Since I was impressed by conductor Richard Müller-Lampertz and his Offenbach recordings from the same years, I was hopeful that these Genée shows might equally jump off the page and inspire me. (To read more about these Offenbach recordings, click here.)

Isabelle Everson as “The Royal Middy.” (Photo: Dario Salvi Archive)

Let’s start with Seekadett, a show recently reconstructed by Dario Salvi who released a book containing the various editions of The Royal Middy at Cambridge Scholars. It contains three English language versions (incl. the one Emily Soldene’s company performed for years), two German versions (Vienna and Stuttgart), one in French (with an alternative scene from the Bruxelles production) and one in Italian.

The Dario Salvi edition of Genée’s “The Royal Middy / Der Seekadett.” (Photo: Cambridge Scholars Publishing)

On the CD you get nine highlights from this show about a young Parisian soubrette running after her ex-lover to Portugal where she discovers he’s married the Queen of Portugal, without anyone knowing about it. When the queen shows up the soubrette has to hide to avoid a jealous high-noon situation, so she disguises herself as a royal middy who in turn charms Her Royal Highness. Until, in the end, she changes back into female attire, leaving the queen bewitched, bothered and bewildered, and disbelieving the sex change. The queen goes public with her secret husband, and the soubrette marries an ultra-rich Brazilian who’s been onto her for three acts.

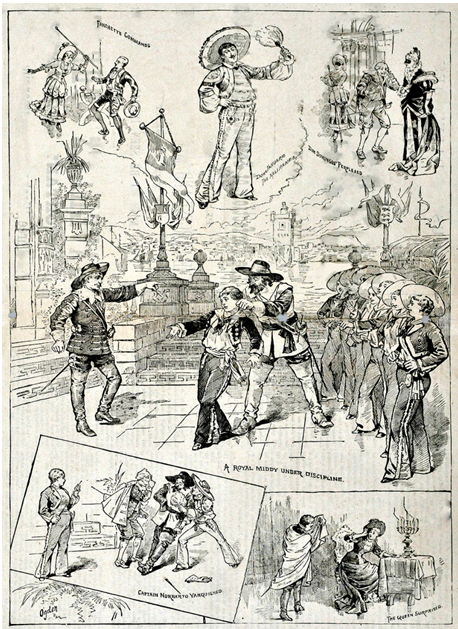

Haverly’s Theatre promotional leaflet for “The Royal Middy.” (Photo: Dario Salvi Archive)

It might sound like a ludicrous plot, but it allows for a lot of cross-dressing and homoerotic momentum between the two ladies. There’s also a famous chess scene in act two in which the royal middy helps the queen win the game: a game in which all the chess figures are played by real-life actresses (i.e. the other naval cadets) who can be moved around by command.

On the recording, the Brazilian’s entry song “Ich bin Dom Januario” (“Bin geborener Brasilianer, Süd-Amerikaner, Nachbar der Indianer“), lamenting that he doesn’t know how to spend all that money of his made from producing rice, coffee, cacao, cotton etc., is performed splendidly by tenor Rupert Glawitsch, with stunning orchestral effects that make you listen up. But: on the whole the music never takes off like the Brazilian’s rondo from La Vie parisienne, and also in the other numbers Genée rarely manages to create a tune (or scene) that sticks in your memory, though the music bounces along pleasantly. Another example to illustrate this would be the march of the cadets (“Wir sind die Cadetten, / Die netten, adretten, / In Glied und Reih’, / Zu Zwei und Zwei”): if you compare this number with the rousing Suppé marches from Boccaccio or Fantinitza you’ll understand that it wasn’t Genée’s forte to write those big blockbuster tunes.

Or did he, and they just don’t come across the right way on the recording? I cannot say. Obviously this is a 1950s type of ensemble and operetta approach. So the overall feeling is “classical,” with Heinz Hoppe as the secret husband of the queen, Sonja Schöner as the soubrette and Benno Kusche as a comic side kick.

What Genée does best – working with vocal ensembles

In my puzzlement I asked Dario Salvi what he has to say about the musical qualities of Genée. His reply is this: “Seekadett is Genée doing what he does best – working with vocal ensembles. The score is not an easy one for operetta standards and less immediate to the ear than those of Suppé, Millöcker or Ziehrer. It is harmonically more complex, and it experiments more with unusual rhythms and time signatures. I performed it three times in Philadelphia (with string quintet and piano, in my own orchestration with original string parts and piano to cover for winds and brass). Seekadett is in the pipeline for a future recording as well. It is very interesting as it is a step up from Nanon and it features musical ideas (not melodies) adopted in Freund Felix (which is amazing!) and Der Geiger von Tirol, a Romantic Opera more than a Comic One. Genée surely deserves to be rediscovered in it full glory!”

Dario Salvi also points out that the music you hear on this Hamburg recording was rearranged, i.e. it’s not Genée’s original orchestration. (That said, the orchestrations sound absolutely fine, there’s nothing seriously wrong with them.)

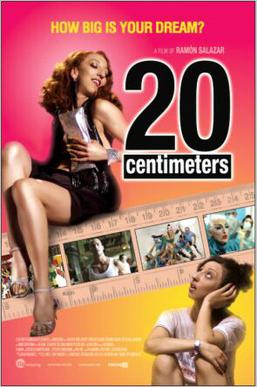

By coincidence I was watching the Spanish musical comedy movie 20 Centimeters the other night, with some swirling dance scenes and amorous chaos; I wondered how Seekadett might work if you added some trans aspects to the story and gave the cross-dressing a different level of meaning. And perhaps also make it feel more relevant from today’s point of view.

Poster for the 2005 film “20 Centimeters” by Ramón Salazar, with Mónica Cervera as Marieta and Pablo Puyol as Raúl, the man who loves “all” of Marieta.

Obviously, a trans woman’s voice is very unlikely to sound like the chirping Sonja Schöner, who possesses a delightfully light soubrette soprano typical of the era. But if Dagmar Manzel can successfully make a Gitta Álpár role her own (in Ball im Savoy) any accomplished trans woman (tenor, baritone, bass, or counter) could do the same, with or without 20 centimeters.

I also wondered where the rest of this Seekadett from Hamburg might be, and why it hasn’t been released by Cantus Classics? The highlights don’t really allow you to get a feeling for the full show.

A farce set in 18th century France

The same might be said about Nanon – a French farce in three acts. Each act is set in a different lady’s boudoir where the same scene plays out in a variation. It’s erotically charged stuff, and totally in the style of “pornographic” 19th century operetta. But obviously you’re not going to hear any of that on a 1955 recording. It’s Sonja Schöner and Heinz Hoppe again, and it’s a very “classical” approach again, with some lovely singing and orchestral playing. But it doesn’t make the sensual (or sexual) tension of the farce set in 18th century France palpable, with the notorious Ninon de Lenclos as one of the three central characters. Again the big vocal ensembles have a lilting quality and sound very appealing, but again they rarely make a lasting impression, musically speaking. They might work better if you see them on stage – in a congenial staging. Which you probably got at the Theater an der Wien in 1877.

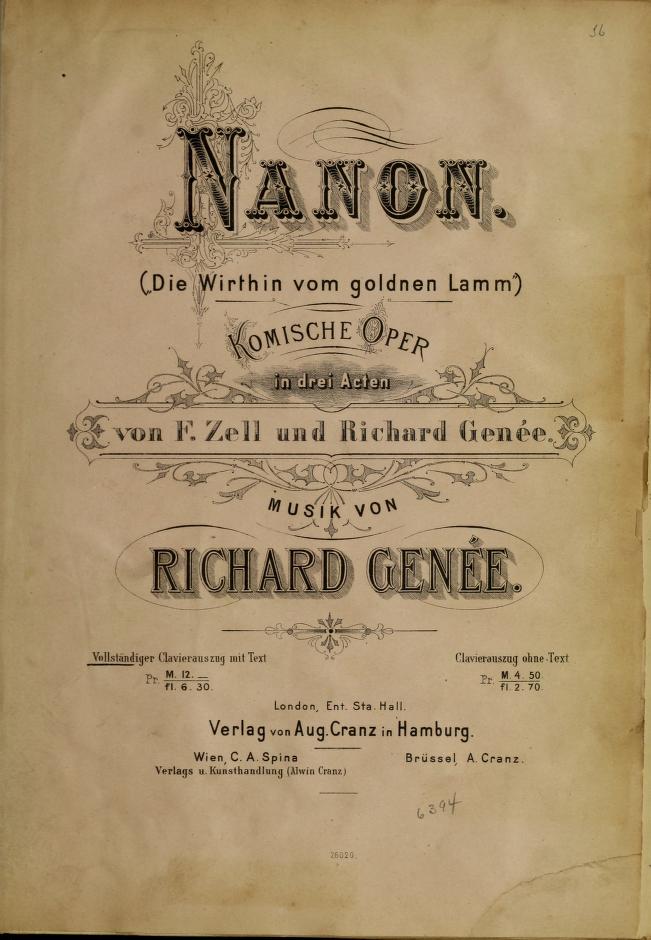

The music for Genée’s “Nanon.”

Which leaves Der Musikfeind. It sounds like a Lortzing opera here, and it’s always a delight to hear Siegfried Vogel who sang the role of Jupiter in the 1974 DDR movie version of Orpheus in der Unterwelt. There are some delightful scenes like the one in which the young lover pretends to be entirely unmusical and sings so far off key when tested by the “music hater” that’s it’s hilarious to listen to. Again, this being a 1950s recording, the style remains “classical” throughout and such scenes stay kind of “contained,” even in East Germany.

I admit that I never got to Rosita as the last item on the double disc, because I simply got bored with the music, or at least the way it sounds here. Instead, I started reading Klotz, Schneidereit and Salvi. And began dreaming of a mash-up of Seekadett and 20 Centimeters. Maybe add Nanon to the mix, too.

The film version from Nazi times

By the way, there’s a 1938 film version of Nanon with Johannes Heesters and Erna Sack. It’s one of the many attempts of Nazi propaganda minister Goebbels to bring “classic Viennese operetta” back into circulation as a shining example of a “non-Jewish” and (according to that logic) “superior” type of operetta.

While I’ve always enjoyed listening to Erna Sack’s coloraturas, the film has put me to sleep long before this double disc did. Maybe that’s because Heesters is nowhere near as interesting as Pablo Puyol as the hunky lover who agitates the ladies in 20 Centimeters. And the original erotic flair of the Genée libretto is killed by a typical Nazi musical comedy harmlessness that makes me wonder what the point of this operetta film was supposed to be. It presents Viennese operetta as a different kind of “classic” that – from today’s point of view – is even more problematic than the 1950s approach on the CD.

A “Film-Kurier” issue from 1938 dedicated to the “Nanon” movie version staring Johannes Heesters.

That said, of course this film Nanon is an important historic document that has influenced many people’s idea of Genée, to this day. Maybe it is high time to change that. So I do hope that my two operetta friends who outed themselves as Genée aficionados will get a chance to prove that there’s more to him than we could imagine.

I hope so, because I have a vivid imagination when it comes to forgotten 19th century operetta!