Roland H. Dippel

Operetta Research Center

28 March, 2017

It’s a sad fact that the West-German publishers Schott and Bärenreiter – who took over the performance material for many former East German popular musical theater shows after the reunification of Germany from the publishers VEB Lied der Zeit and Henschel – do very little to promote the various works they have incorporated into their catalogues. As a consequence, the shows remain mostly unperformed and unknown today, and any academic debate of DDR shows is only slowly moving forward. One positive exception was the symposium Popular Music Theatre Under Socialism (Operettas and Musicals in the Eastern European States 1945 to 1990) in February 2017. The symposium was held at the Center for Popular Culture and Music, University of Freiburg, in collaboration with the Institute for Art History and Musicology, Department of Music Science of the University of Mainz.

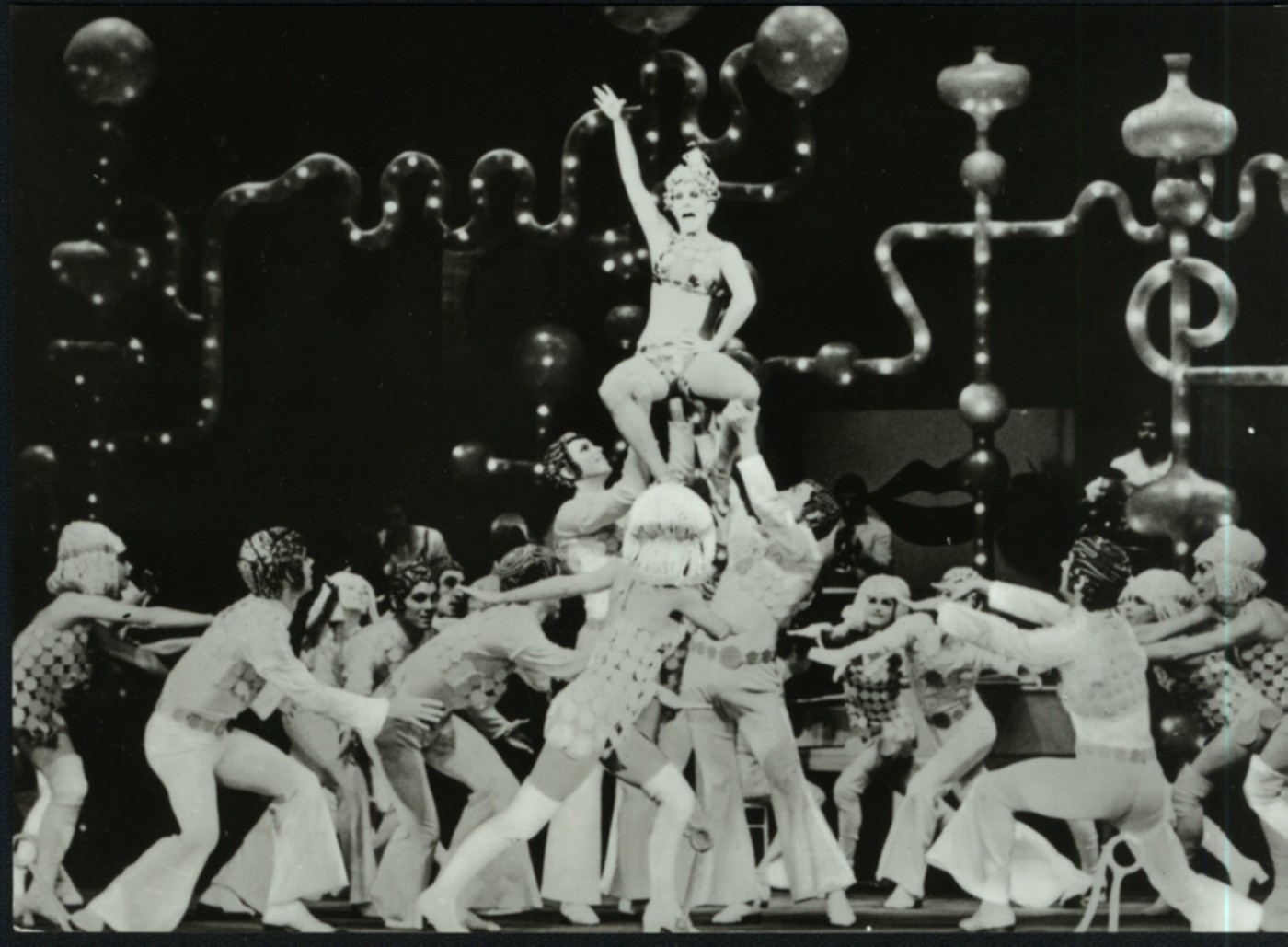

Poster for the revue “Die Frau des Jahres,” performed at East-Berlin’s Friedrichstadt Palast 1963.

But is it just the publishers who are to blame here? No, I believe one of the main reasons for the general neglect are the original participants and eye-witnesses themselves. At least that is the experience I have made while dealing with many representatives and musicians of the Musikalische Komödie in Leipzig, one of the two prominent former DDR operetta stages. While I was there to prepare for my 15-part series of newspaper articles entitled „Operette und Musical der DDR,“ former chief conductor Roland Seiffarth – a close friend of DDR composers Guido Masanetz, Conny Odd and Gerhard Kneifel – told me in no uncertain terms that no one from the post-1989 generation is interested in the specifics of popular musical theater of the DDR. No reasons given. No further discussion necessary. Erwin Leister, who worked as a stage director at the Musikalische Komödie for many DDR years, claims that many musicians had been forced to change from opera and drama to operetta and musical back then – which left deep wounds in their self-esteem as artists. It’s an interesting theory: the neglect of operettas and musicals from the DDR is based on a widespread uncertainty of the former protagonists about the genre. Did they invest so many years of their lives and so much energy into shows that are looked down upon as musically banal and politically intollerable by many today, who don’t even bother to take a closer look at any of the titles in question?

Scene from the DDR show “Eine Frau nach Maß,” 1971.

Under such circumstances – considering the unwillingness of the eye-witnesses to discuss the past – it is even more important to examine the historic documents left by those once in charge and responsible for this unique group of works created for the Socialist theater system of East Germany. Because such original documents give us insight into the political and personal backgrounds of the participants. But even though there are original documents, many heirs withhold them from the public and from researchers. One example is the once popular und highly successful East-German composer Gerd Natschinski who died on August 4, 2015. A few months later, his former operetta colleague Guido Masanetz also died, on November 5. This marked the definite end of an era which had actually come to a finish back in 1990 when the once separated Germany was reunited. After that the former shows from the East were cast aside, as if they were toxic and needed to be hidden from sight.

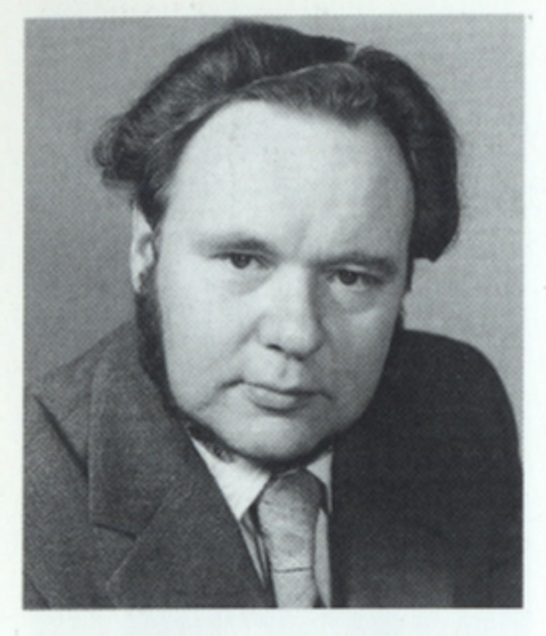

Composer Gerd Natschinski. (Photo: William Pauli)

One year before his death, in 2014, Gerd Natschinski sent me chapters from his fragmentary memoires, covering the creation of his 13 once successful stage words. Later, his widow Gundula gave various public lectures based on these memoires, but there is no information whether they will ever appear in print. Upon my asking for more information – for a book project dealing with the operetta scene in the DDR – the Natschinski family never responded.

The legal situation regarding these memoires – if you wish to quote from them in academic articles etc. – is problematic until the family makes a decision regarding publication.

After having read the chapters on musical theater, I admit that a publication of the entire manuscript is not exactly urgent, because there is not much new information to be found. Or differently put, there is not more information in the memories than in the newspaper interviews that are accessible, from the time pre and post 1989. Still the memoires are a document in which Gerd Natschinski himself talks about his life, his oeuvre, his past. And it’s nearly as important to see what he does not talk about. That’s indeed a story worth analyzing. At the moment, the conductor and university lecturer Michael Stolle is preparing a biography of Gerd Natschinski. Obviously, selections from the memories should be utilized for and quoted in the book.

Gerd Natschinski composed 12 stage works and one ballet based on Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann. After 1989 and the German reunification he stopped composing altogether.

His break-through had been the operetta Messeschlager Gisela in 1960. 24 theatres followed the triumphal first production, later it disappeared from DDR stages. Still, there is a TV production directed by Erwin Leister with Eva-Maria Hagen, mother of rock legend Nina Hagen. She plays the “decadent bitch” Margueritta. Erwin Leister told me in 2016 that one reason for the abrupt stop of performances of Messeschlager Gisela was the humorous depiction of the “free” West vs. a satirical portrayal of socialistic life, and characters moving back and forth between the two worlds – which seemed particularly inappropriate after the building of the wall a few months after the world-premiere.

Poster for the revival of “Messeschlager Gisela” in Cottbus, 1999. (Photo: Archiv Roland Dippel)

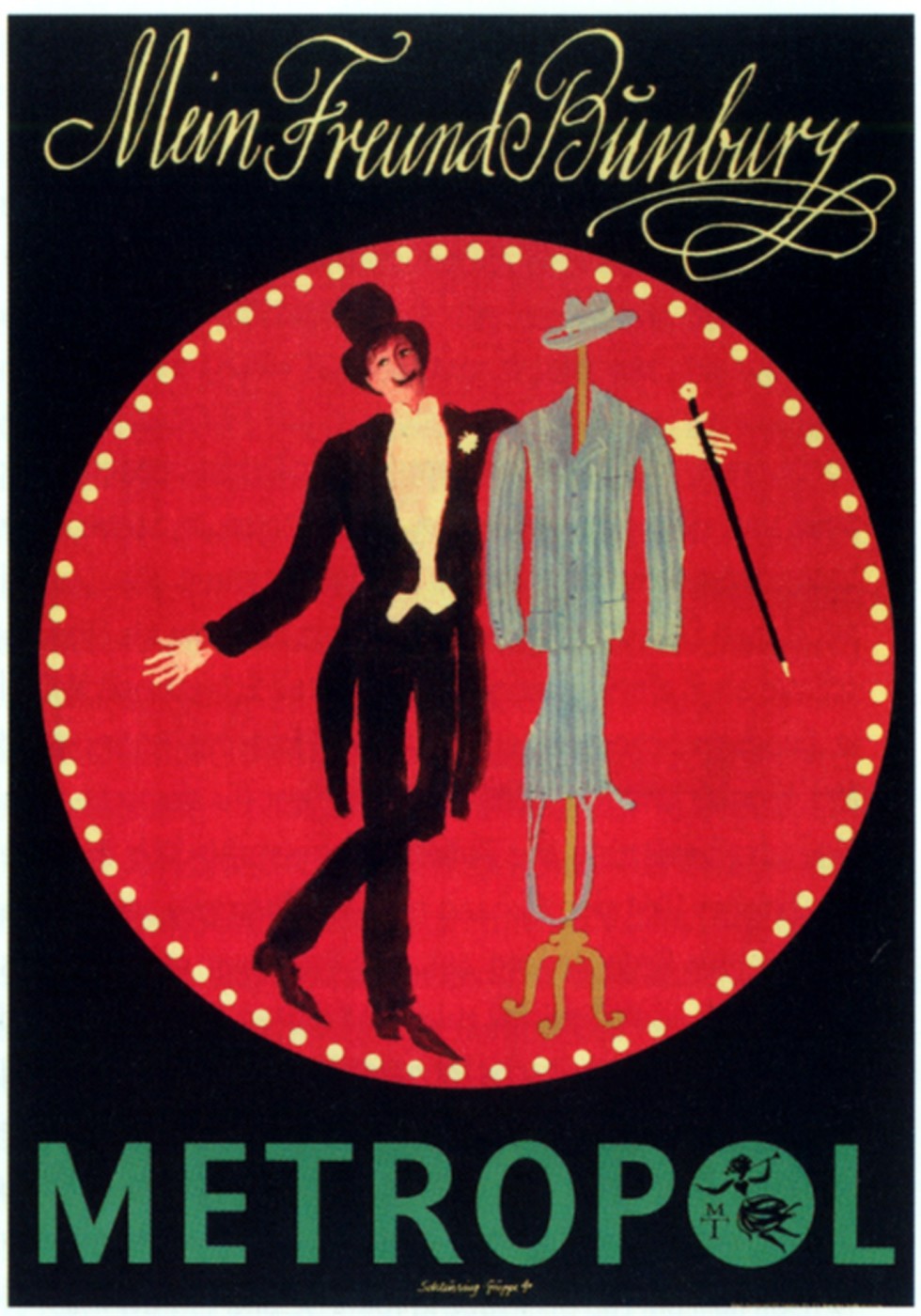

After the death of Hans Pitra, Natschinski was made new artistic director of the Metropoltheater in the Admiralpalast, close to the transit point between the Eastern and Western parts of Berlin. He never joined the political party SED. Still, his film scores and songs became favorites in the politically controlled theatres, radios, cinemas and TV broadcasts of the DDR. He refused theoretic and artistic discussions about contemporary “plots.” After his hit Mein Freund Bunbury – an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest – in 1964 he turned to other historic stories like Casanova or Ein Fall für Sherlock Holmes. His only contemporary operetta after Messeschlager Gisela was Terzett in 1973: it’s a reflection on the legend of Count Gleichen who married two wives and shared one tomb with them. This fairy tale is treated as a metaphor for a new Socialist reality – two ladies and one guy happily living together.

Poster for “Mein Freund Bunburry” at the Metropol Theater in East-Berlin, 1973.

The memoires contain reflections on his stage works and two so called “Intermedias” about his life as a husband and father. We learn that Natschinski disliked his first operetta Der Soldat der Königin von Madagaskar and also the second version of Kamilla ist an allem schuld, as an example of the anachronistic style of DDR operettas before 1960. He reports that Jo Schulz‘ play Messeschlager Gisela won the first prize at a competition for new themes in theatre.

In his memoires, Natschinski doesn’t talk about the reasons why Messeschlager Gisela wasn’t performed in the DDR after the building of the wall, but he does mention the movie version directed by Erwin Leister. Several chapters deal with his “friendly rivalry” with Guido Masanetz. Masanetz was his strongest competitor for the top position in the field of socialist popular musical theatre.

In two instances Natschinski refused to set plays to music. The first, Mein schöner Benjamino (1963), was instead composed by Masanetz. The operetta was a flop. He also turned down a musical adaptation of the play Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten, based on the famous German comedy Der Raub der Sabinerinnen. Natschinski was not interested, even though the libretto was by his longtime partners Helmut Bez and Jürgen Degenhardt. Natschinski was put off by the “bourgeois setting” of the piece, and so Gerhard Kneifel composed the music instead. It turned out to be a smash hit in the DDR.

The DDR operetta “Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten,” 1969.

Regarding Mein Freund Bunbury, Natschinski reports of a clash of opinions with the stage director Charlotte Morgenstern, and he claimed that he did not know My Fair Lady before composing Bunbury – which is, in many ways, a direct role model. Many people suspect that Natschinski wanted to copy Loewe’s famous musical comedy to create a cheaper East-German alternative to the expensive Western sensation for which high royalties had to be paid.

After the revue Die Frau des Jahres at Friedrichstadtpalast, Natschinski paused until Terzett in 1973. During rehearsals he fell in love with his second wife, Gundula. After meeting her, he embarked on a second career as intendant of the Berlin Metropoltheater.

A special case is his six part musical comedy ABC der Liebe, based on stories from Boccaccio’s Decamerone. A young lady and a young guy discuss the difference between medieval and contemporary “free” love. Natschinski was also proud of productions of his shows in Western Germany: Bunbury, Terzett, and Casanova were produced in Gelsenkirchen, Munich, Detmold and other theatres.

After fall of the wall and the reunification Natschinski retired and conducted some concerts throughout Germany.

One can only suspect the reasons for the sudden end of his composing career. Did he feel the end of his era had come with the end of the DDR? Couldn’t he imagine continuing under new political conditions?

Natschinski didn’t believe in contemporary plays from the DDR. For Cottbus, he recommended Casanova for revival (says the local intendant, Steffen Piontek) and opposed a plan to restage Messeschlager Gisela until he saw how happy audiences were to see it – and its witty socialist story.

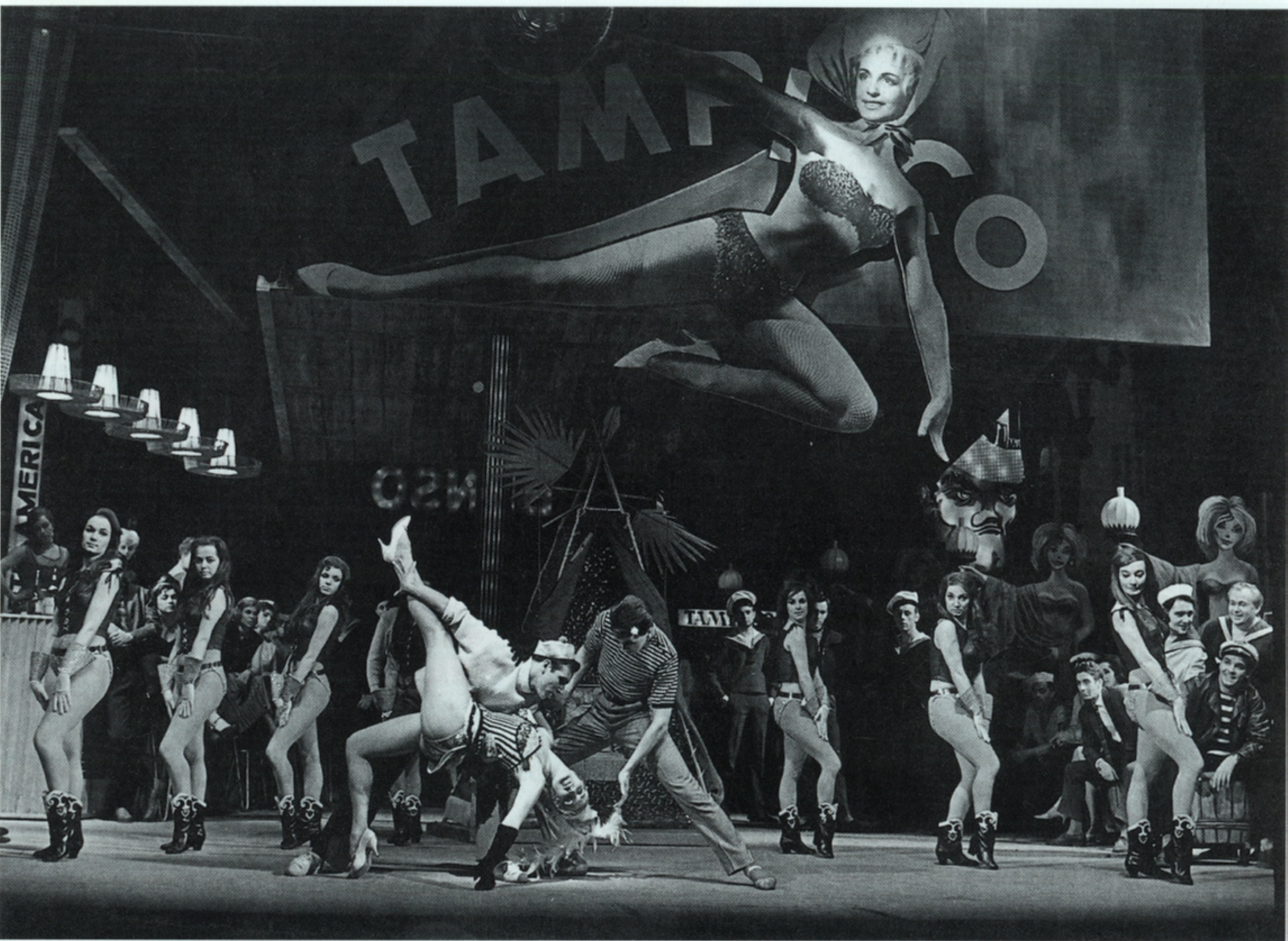

A scene from “In Frisco ist der Teufel los,” 1962.

So where does this leave things? The Musikalische Komödie Leipzig recently put on a concert performance of Masanetz’s socialist masterpiece In Frisco ist der Teufel los (about the evil capitalists in San Franisco exploiting poor workers in the harbor who eventually unite and bring down the system). The performance was sold out and a second performance had to be scheduled to fit the high demand. Yet a new generation of researchers and theaters goers is not made fully aware of the potential of this body of work and the fascinating background stories – political and musical – that are there to discover. Hopefully, books like the new biography written by Michael Stolle, symposiums like the one in Freiburg and further exhibitions, publications and TV documentaries will change this situation, including more performances in Leipzig and elsewhere. And hopefully we will not have to wait until everyone once involved is dead to clear the path for something new, instead an open and critical dialogue with the protagonists of the past would be desirable.

![Poster for the DDR show "Für 5 Groschen Urlaub" [Holiday for a Dime], 1969.](http://operetta-research-center.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Für-5-Groschen-Urlaub-Metropol-1969-e1490768110839.jpg)

Poster for the DDR show “Für 5 Groschen Urlaub” [Holiday for a Dime], 1969.

Haben Sie schon einmal etwas von der Staatsoperette Dresden gehört? Führendes Musical-Theater in der DDR! Übrigens fand dort am 30.Oktober 1965 die DDR-Erstaufführung von “My fair Lady” statt, es folgten 446 Aufführungen.

Empfehle bessere Recherche.

[…] Deutsche Übersetzung des Beitrags in englischer Sprache: http://operetta-research-center.org/gerd-natschinski-ddr-operettas/ […]

[…] http://operetta-research-center.org/gerd-natschinski-ddr-operettas/ […]