Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

27 August, 2016

Because of popular demand – and there obviously is much demand in New York City right now – the production of The Golden Bride returned to the Manhattan theater-scene for a summer season. It had already been performed, half a year ago, at the Museum of Jewish Heritage down at Battery Park. It is now back for a whole month of new performances that are actually better attended and nearly always sold out, probably because there are so many tourists in the city at the moment, eager to explore musical theater. If they can’t get into the big Broadway smashs Aladdin or The Book of Mormon (or Hamilton), they can book reduced tickets via the Times Square ticket booth and go see a Yiddish operetta from 1923, which originally premiered at the 2,000-seat Second Avenue Theater where it ran for 18 weeks before touring to Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Chicago, Detroit and other American cities. Not to mention Buenos Aires and Manchester, UK.

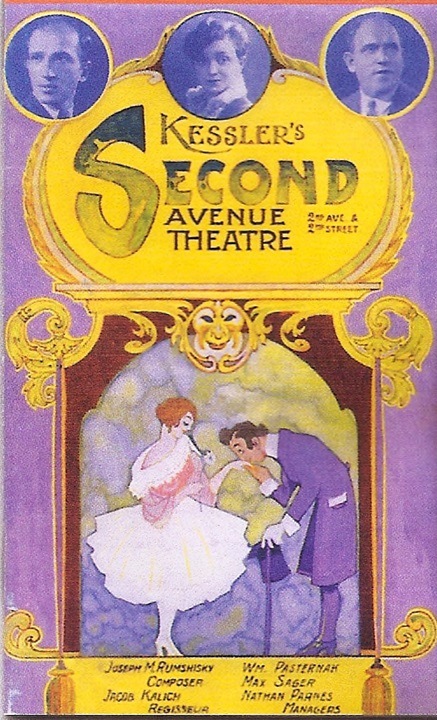

Advertisment for Kessler’s Second Avenue Theater, for a production of a Jopseh M. Rumshisky [sic] operetta.

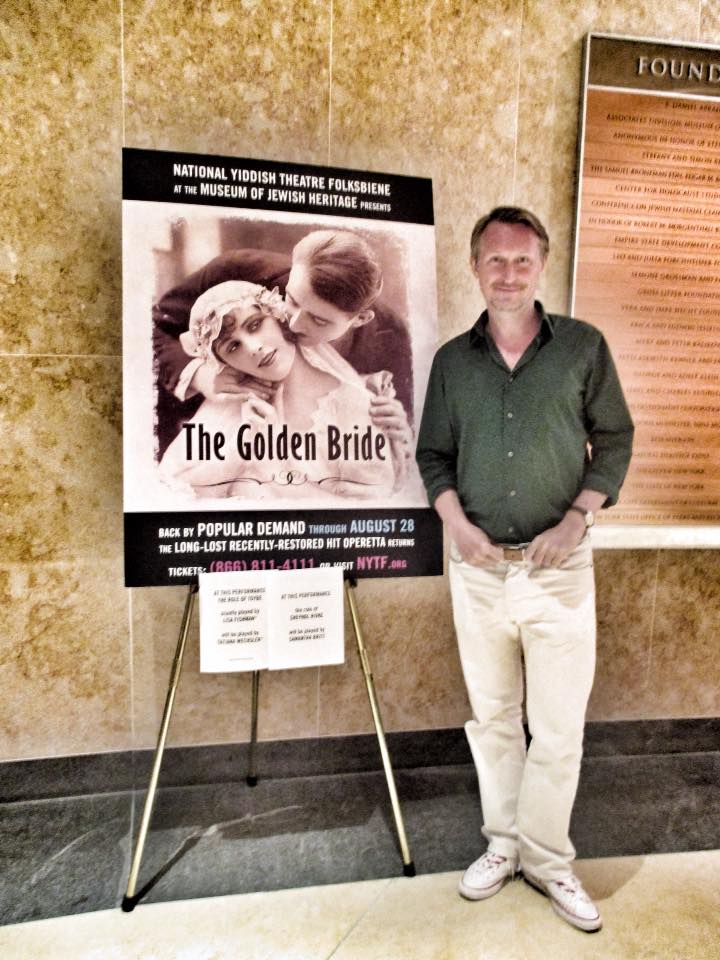

Kevin Clarke in the foyer of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene.

If you like your operettas to be lush melodious offerings that make no demands on the intellect, then The Golden Bride is not for you; even though there are many charming melodies in Joseph Rumshinky’s score. But in terms of lushness and melodic splendor, you can’t beat the likes of Lehar, Künneke, Kalman or Lincke, not to mention the US greats Victor Herbert, Sigmund Romberg or Rudolf Friml. However, if you want to be intellectually challenged, at least a little bit, by historical context and background, then The Golden Bride is definitely a show you want to see. It mirrors the social turmoil in Europe in the early 1920s, in this case the Russian Revolution and the subsequent migration of many Russians to Western Europe and to the United States, which is seen here as the promised land of unlimited possibilities and syncopated music – as opposed to the old-fashioned world of Europe with its more traditional musical styles of waltzes and marches.

Yiddish theater composer Joseph Rumshinsky as a young man.

Here, you experience the story of Russian Jews living in a small Russian village who are confronted with rich visitors from the United States; that’s Act 1. In Act 2, the visitors from the US have taken Goldele (the golden bride of the title) with them to Chicago, where she enjoys the high life made possible by an inheritance from her late father who had gone to the States years before, leaving his family to make a fortune. In Chicago, some of Goldele’s old friends from back home show up, and there is a definite culture shock moment when they are confronted with the different customs of the new country. But they adapt, and they are ready for a new liberated life on the new continent.

Even Goldele’s long lost mother shows up and has a truly touching story to tell why she gave up her baby 18 years ago.

It’s a rather realistic story, not some cheap melodrama. And it reminds the viewer of the harsh social realities in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century.

Rumshinsky handles the different musical style with great ease, he moves from catchy vaudeville songs to melancholic lullabies to rousing marches and syncopated jazz numbers effortlessly. Some of the score sounds like Victor Herbert and Paul Lincke, then again the snappier US dance numbers are reminiscent of Jerome Kern. And in-between there are lovely Russian flavored solos and a rousing Yiddish ceremonial finale for Act 1. The combination of elements is remarkable, and highly distinctive. And all of it is sung – and spoken – in Yiddish, with English and Russian subtitles.

This “small version” of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene at the Jewish Heritage Museum – put together by Zalmen Mlotek as conductor and musical director – has the merit of being faithful to the original script, in the sense that it offers more or less the full text and the full music, in a no-nonsense production. (Which is a remarkable experience after a full season of German deconstruction theater!) The singing is generally good, with Cameron Johnson as Misha (the soulful Russian boyfriend) and Glenn Seven Allen as Jerome (the cocky nephew from Chicago) as the stand-out performers, one with a ringing youthful tenor voice and frightful good looks (Johnson), one with a perfect sense for comedy and a suave stage presence (Allen).

Tenor Cameron Johnson. (Photo: National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene)

The young ladies were more on the shrill side and much more “inhibited” in their acting, but worked well with their partners: Rachel Policar as Goldele and Rachel Zatcoff as her friend Khanele. (The latter fresh from the Broadway production of Phantom of the Opera where she played Christine.)

Cameron Johnson (Misha), Rachel Policar (Goldele), and Company in “The Golden Bride.” (Photo: Ben Moody)

Much as I loved seeing the show and getting to know the piece by Louis Gilrod (lyrics) and Frieda Freiman (libretto), and as fascinating as I found Rumshinsky’s score, I missed the full-blown vaudeville elements in this productions, elements that were clearly in the original 1923 version. Some of the scenes are pure slap stick, but here they were presented with too much care and distance, almost like typical Ohio Light Opera productions. [For Harry Forbes’s review of the 2016 OLO season, click here.] The Golden Bride would benefit from a more over-the-top portrayal of all characters, from more down-and-dirty dance routines, and from more rough-and-ready entertainment.

Grand gestures at the Second Avenue Yiddish Theater, 1910: David Kessler, Jennie Goldstein and Malvina Lobel in Joseph Lateiner’s “The Jewish Heart.”

I’m aware that I was at a Heritage Museum where the emphasis is on preservation, but if you want to give a show like Golden Bride a real second life you should opt for more than a dutiful rendition of the text. And you should also get actors with a more idiomatic command of the Yiddish language.

Hearing all of them labor with the Yiddish text killed a lot of the authentic flavor: a flavor that is one of the best selling points of the show.

The original Playbill for “Di goldene Kale,” 1923. (Photo: Steven Ledbetter Archive)

As it is, this is nonetheless a production lovingly put together by everyone involved, and it’s a rare chance to actually experience this slice of Yiddish and operetta history. No, The Golden Bride is not a milestone like The Merry Widow or Countess Maritza, because it was created and performed in a distinct niche (very much like the Off-Broadway LGBT shows of the 1970s). But it offers an important outsider comment on the happenings all around. And hearing some of the praises of the USA, in the patriotic chorus numbers, right in the middle of the US election campaigns, makes you realize that some ideals have not changed much since the premiere of The Golden Bride in 1923. These numbers got great laughs from the audience, incidentally.

The makers of “The Golden Bride” are thinking about recording this production and/or sending it on tour, just like the original “Di Goldene Kale” toured extensively.

It would work well, in terms of performance and production style, at OLO in Wooster. Not surprisingly, one of their chairmen, Michael Miller, already went to see it earlier in August and loved the show as well as this production. It would definitely be a valuable addition to the Kurt Weill Festival in Dessau, too, where they invite groups from outside to present shows that can be contextualized with Weill. And Golden Bride certainly can.

As a reconstructed score and script, put together from archive material by Mr. Mlotek, The Golden Bride absolutely deserves productions – on the stage or in concert – in Germany or Austria, maybe even Russia. Whether the Komische Oper Berlin will offer Rumshinsky a concert opportunity in their concert operetta series remains to be seen, or the WDR radio in Cologne or the BR forces in Munich? The staging in New York is a basic yet attractive one, which could easily travel. But the show with its limited cast would just as easily work on a concert platform. I myself would love to have a recording of this 1920s operetta hit, but I would prefer a more exaggeratedly acted out version for my CD collection, with a bouncier orchestra. And definitely with better Yiddish. (Issued by labels such as cpo, Naxos or an American company?)

Musical director Zalmen Mlotek at the piano. (Photo: www.zalmenmlotek.com)

Who knows, sometimes dreams come true. The mere fact that Zalmen Mlotek and the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene have managed to resurrect Di Goldene Kale on such a scale – and with such massive international feed-back – is an achievement that stands out in the current operetta scene. It cannot be lauded enough.

The bottom line is: Rumshinsky is a composer to rediscover. And Mr. Johnson and Mr. Allen are destined for (more) future operetta glory, Yiddish or otherwise!

Leading man Glenn Seven Allen. (Photo: National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene)

For more information on the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, click here.

what good lookers you guys are – all three!!!

Hi Kevin Clarke. Having spent some four years restoring “The Golden Bride,” I was surprised and a bit dismayed to find that you credited my work to someone else–in this case, musical director Zalmen Mlotek, who, together with the co-directors Bryna Wasserman and Motl Didner, did a fantastic job of bringing the work to the stage. If you had read the program notes or, indeed, the excellent review by Steven Ledbetter that was reprinted by the Operetta Research Center itself (http://operetta-research-center.org/1923-yiddish-operetta-astounds-new-york-city-audience), not to mention the NY Times article of 11/28/15 (http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/28/theater/preparing-the-golden-bride-for-its-big-day.html), you would have found details about the restoration. And as for the theater-Yiddish pronunciation by the cast, I can only report that cast members were constantly approached by Yiddish speakers who addressed them in Yiddish on the assumption that the cast spoke the language fluently.