Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 August, 2015

It’s not a new topic, but a brand new book nonetheless: Black Broadway by Stewart F. Lane. According to the title page it wants to present “An Illustrated History of African-American Struggles & Triumphs on the Theatrical Stage,” or more precisely “African Americans on the Great White Way.”

Stewart F. Lane’s “Black Broadway.”

Mr. Lane is a six-time Tony Award-winning Broadway producer. His list of shows includes War Horse, Thoroughly Modern Millie, A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder, La Cage aux Folles, and The Will Rogers Follies. Which is quite an impressive collection of Broadway history in itself. He has previously written the book Jews on Broadway, so it seems he’s tackling one “minority” group after the other that has left a decisive mark on musical theater in the US.

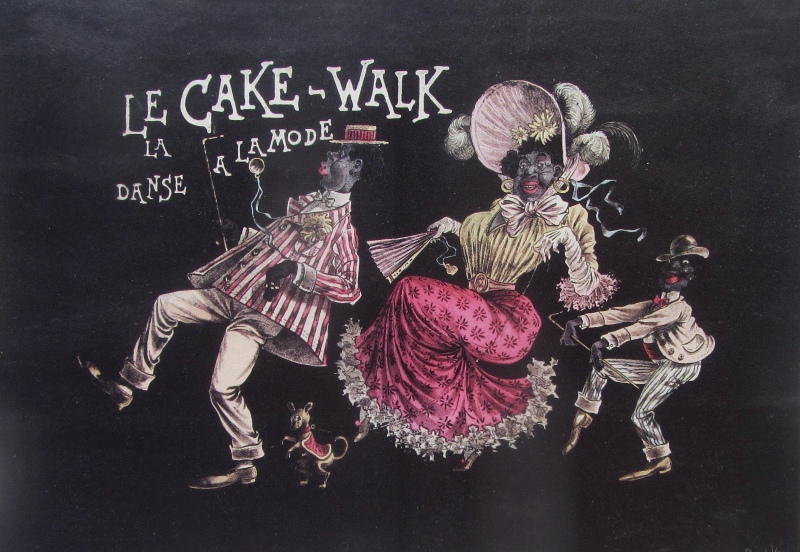

This story begins in 1821 when Alexander Brown, a free black man, took the money he had earned as a ship’s steward and founded the African Grove Theatre, the first known theatre established by and for African Americans in NYC. Lane then chronicles, chapter by chapter, how (a) blacks were represented on the stage, for example by whites in “black face” as part of minstrel shows and how (b) they themselves performed in shows. They started out in minstrel shows, presenting grotesquely exaggerated versions of themselves, and they brought new rhythms and dance moves to Broadway –from Dixie to cakewalks to ragtime and spirituals. Not to mention tap dancing, which became an integral part of American showbusiness.

In the late 19th century the cakewalk became a craze. (Photo: Stewart F. Lane’s “Black Broadway.”)

While Mr. Lane’s book is richly illustrated and beautifully designed, his narrative is not especially thrilling. It’s often a simple “A does this” then “B does that” formula that quickly becomes tiring because there is never any analysis of anything. Lane only covers the absolute surface without taking a wider political perspective. I found this especially disappointing after having just read Andrea Most’s amazing book Making Americans: Jews and the Broadway Musical before. Where Most offers brilliant intellectual interpretations and delves into revelatory readings of shows, Mr. Lane gives hardly more than a plot summary. Certainly no close reading of the productions in questions, nor their stars. If you just want a quick and colorful overview then this book is perfect. If you want to find out more about the meaning of being black on Broadway, then this is not the right publication for you.

From an operetta perspective, there are some amazing details to be found, though. For example, Lane mentions an “all black” version of Gilbert & Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore by the radio program New World A-Comin’ in 1946. The G&S broadcast was part of the activities of the American Negro Theater, ANT, in the mid-1940s.

The 1939 production of “Swing Mikado.” (Photo: Stewart F. Lane’s “Black Broadway.”)

The other operetta section in the book covers yet another G&S title: The Mikado. It was given an “all black” interpretation in 1939, first as Swing Mikado, then shortly afterwards as Hot Mikado. In the first, the action is relocated to “A Coral Island in the Pacific.” The production was conceived, staged, and directed by Harry Minturn. It opened in Chicago in 1938, and moved to New York the year after. Some dialogue was re-written in an attempt to simulate black dialect. But most of the music remained unchanged, with only a few syncopated rhythms added, plus a cakewalk.

It was quite a high profile event when it opened in New York, the first night being attended by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and NYC major Fiorello LaGuardia.

The reviews, however, were not too positive. Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times as well as others complained about the “lack of swing.” They all wanted more “swingcopation.” They certainly got that in a rival production of Mike Todd’s Hot Mikado which featured Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in the title role. You can see him here, without sounds alas. But it’s an impressive film document anyway.

This was a much jazzier affair, on a big budget that allowed for wild costuming and elaborate visual effects. Opening at the Broadhurst Theatre on March 23, 1939, the Hot Mikado was greeted with enthusiasm by both theatergoers and critics, with Newsweek’s George Jean Nathan calling it the “best all-around musical show” of the season.

What is sad – and typical for the book – is the fact that Mr. Lane, in the context of the “Battle of the Black Mikados,” does not mention Erik Charell’s 1939 Swingin’ the Dream, an “all black” musical version of Shakespeare Midsummer Night’s Dream. Admittedly, this show was not a success, but it would have deserved a mention here, perhaps even a photo.

After all, there were major stars involved such as Louis Armstrong as Bottom, set designs based on Walt Disney, Agnes de Mille choreography, and music by Jimmy Van Heusen.

It was presented at the massive Center Theatre where Charell’s previous White Horse Inn had been a smash. Plus: Charell himself had staged an early jazz version of Mikado in Berlin, in the mid-1920s.

In the context of later shows presented in the book, Mr. Lane describes various attempts to re-interpret classics such as Hello Dolly with all black casts. He also discusses Oscar Hammerstein’s black version of the opera Carmen as Carmen Jones in 1943. These later productions do not involve operetta titles Unless you count Kismet as an “operetta,” in which case there is Timbuktu! starring Eartha Kitt. She is in this book, as is a section on The Wiz based on Frank Baum’s book; it makes for interesting comparisons with the Victor Herbert version. Among other things.

“The Wiz” was transformed into a hit via the support of the black community. (Photo: Stewart F Lane’s “Black Broadway.”)

Lane doesn’t ask what possibilities “ethnic” re-interpretations of shows mean, or can mean, nor how this approach of all black re-casting might work if you cast other famous titles only with Asians, gays, women, or any group you care to chose. But it is inspiring to look at black theater history in the USA in this luxuriously large coffee table format book. More information about the audiences of the shows in question would have been a plus, since for a long time blacks were either not allowed into theaters at all, or only permitted to sit in the balcony.

All of these points remain an open field some future researcher may plow into. Till then, I can only hope that companies such as the Komische Oper Berlin, devoted to jazz operetta, will take a closer look at the Hot Mikado – especially since Erik Charell himself presented a jazz version of Der Mikado at the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin, with Max Pallenberg as the star. That performance material is lost, even if a few recordings survive. But the Hot Mikado should be a lot easier to reconstruct. Also, Kismet/Timbuktu would be a prime candidate awaiting a dazzling German production. At least the Volksoper Vienna will offer a concert staging of Kismet next season, though not with a black cast.

And, please, if anyone has a copy of HMS Pinafore done by the American Negro Theater, let me know!