Jan Neckers

Opera Now/Operetta Research Center

14 July, 2014

Franz Lehár was not the first to think of Goethe as an opera or operetta hero. There was the precedent of Giacomo Meyerbeer who in his old age wrote theatre music for a piece called La Jeunesse de Goethe. The piece was never performed. The idea of a “Singspiel” about young Goethe arose with one of Lehár’s best librettists Dr. Fritz Löhner (or Beda). Löhner – a Zionist and politically active against Nazism – would tragically die in an extermination camp, in vain hoping for Lehár to use his influence.

Franz Lehár with his two original stars, Käthe Dorsch and Richard Tauber.

After the war Lehár said he tried to intervene though there are no documents proving his words. More probable the composer didn’t dare to help as most of his operetta collaborators had been Jewish and Nazi ideologues tried to have his works banished. Moreover Lehár’s wife too was Jewish and it was only Lehár’s call to a local Gauleiter that saved her from arrest when two Gestapo-men appeared at his house. However Lehár’s music was so popular that Joseph Goebbels took a more pragmatic outlook and allowed theatres to perform Lehár’s operettas on condition they erased all traces of Jewish lyricists and libretto writers. Some Lehár operetta’s were forbidden by local Nazi leaders while Friederike was not performed at all in Germany after 1933 or Austria after 1938. A special performance for Goebbels himself in 1940 did not result in lifting the ban. The combination of Germany’s greatest poet as an operetta tenor (created by a half Jew) and a libretto by an outspoken Jew killed all performing possibilities.

Friederike is one of biographical operettas, beloved by many a composer (e.g. Fall’s Die Kaiserin, Kalman’s Kaiserin Joséphine or even the best Flemish operetta Het Meisje van Zaventem, dealing with painter Antoon van Dijck).

The painter Anthony van Dyck, 1615.

Lehár already had two successful outings in the genre with Paganini and Der Zarewich (inspired by Peter the Great’s son Lehár said, though in reality the operetta resembled more the fate of Michail Romanov, brother of Russian emperor Nicolas and emperor himself for 24 hours).

Goethe however was a subject on another level and still considered a half god in the thirties.

Lehár knew very well he would be gravely accused of trivializing but Löhner’s libretto was so well crafted and inspiring that the composer went forward.

Star librettist Fritz Löhner-Beda.

Löhner did his outmost best to introduce historical reality though some operetta conventions had to be respected. Friederike tells the story of one of young Goethe’s great loves and the inspiration she offered him.

The first act takes place in the Alsatian village of Sesenheim where the father of Salomea (20) and Friederike Brion (17) is a vicar. The fiancée of Salomea is the historically correct Friedrich Weyland, a student at the Strasbourg university (Strasbourg had recently been conquered by Louis XIV but everybody still spoke German while the courses at its university were in Latin). Weyland often visits his future in-laws and has brought with him his fellow students Johann Goethe (at the time without the “von”) and Jakob Lenz (another famous German poet). Goethe and Friederike are clearly in love and at the end of the act he first kisses her. The second act takes place in Strasbourg a few months later. There is a big party going on at the place of Friederike’s aunt. She and Goethe once more declare their love and he intends to marry her and leave for Weimar where the Grand-Duke has offered him a splendid position. But the duke’s deputy tells Weyland that only an unmarried man may take it. Weyland convinces Friederike to give up her dreams and she starts to flirt outrageously with Lenz. Goethe is angry and leaves immediately for Weimar with the duke’s representative.

In the short third act Goethe and the Grand-Duke pass through Sesenheim eight years later. In the meantime Jakob Lenz has tried in vain for years to marry Friederike but as she explains “nobody who has ever loved Goethe can forget that experience and marry another”. During his short stay Goethe reminiscences on his youthful love and takes his definitive farewell from Friederike before leaving for Switzerland with the Grand-Duke.

Käthe Dorsch as the touchingly sentimental original Friederike.

There are of course some deviations from historical reality. In the first act the real situation corresponds with the libretto but by the second act operetta and opera are looking around the corner. In reality Goethe had more or less tired of Friederike whom he found utterly charming in her village but somewhat unsophisticated in Strasbourg surroundings. Father Goethe had been informed about his son’s infatuation, didn’t like an early marriage and recalled Goethe to Frankfurt. Goethe immediately obeyed his father’s wish, maybe even somewhat relieved. He didn’t even take the pains of a decent farewell. In the meantime he nevertheless had written some of his best poems. Friederike sacrificing herself in a somewhat ridiculous way is pure musical theatre convention as Goethe in reality only left for Weimar 4 years later. The couple never met again but it is true that after Goethe’s flight that other great poet Jakob Lenz tried to marry Friederike. She refused and after the death of her parents she lived with her sister Salomea and Weyland. She died in 1813, 59 years of age; a short time after Goethe had published his warm-hearted memories of her. Due to the European war at the time she escaped attention but shortly afterwards people started to come and visit her grave on a pilgrimage. It is somewhat strange that “von Goethe” (ennobled by the Grand-Duke) who thought Friederike too unsophisticated took up shop with a working class girl in 1790 whom he would marry 16 years later and who gave him a son.

The reaction in academic Germany when it became known that Lehár would compose an operetta on this topic was one of horror.

Official Germany had never liked the many operas composed on themes by Goethe. Gounod’s Faust immediately got changed into Margarethe as it was considered a blasphemy to the original poem (Provincial theatres which perform in German still use that title). Mignon was considered sentimental nonsense which had nothing to do with Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister. As often happens the opera loving world and the singers couldn’t care less and fell for those operas. For a few years the Vienna Opera was called the “Faustspielhaus”. Still this wasn’t on the ocean deep level of having Germany’s greatest poet singing love songs on the scene. It was considered unimportant that young Goethe himself had written some sentimental “Singspiele”. Lehár and Löhner were not deterred by this averse criticism; often inspired by the main German Lehár-hater Richard Strauss who was almost insanely jealous of Lehár’s (financial) success. The Singspiel (Lehár never called it an operetta) had its successful première in October 1928 but fell victim to Nazism. After the war the operetta was once more revived though it never had the successful flight of Lehár’s most popular pieces.

The 1970s recording of “Friederike” with Helen Donath.

In the seventies Friederike gradually disappeared from the repertoire as did most operettas; a real loss as it is a masterpiece. For the moment there are two official recordings available and some pirated ones. The 1981 complete recording on EMI with Austrian tenor Adolf Dallapozza and Texas soprano Helen Donath as Goethe and Friederike is the best one though the tenor was even more impressive in a 1970 Munich performance.

Yes, I love Friederike and if I had to take one Lehár show to the legendary desert island this would be the one. That is not to say the operetta is perfect as there are three flaws in it. The first one is Löhner’s doing: the reality of Goethe tiring of his love and leaving without a word or even a small letter probably suits our jaded cynical time far better than the flirting nonsense Löhner concocted. But the public of the twenties and thirties wouldn’t’ t have accepted such a callous behaviour from the hero and loved that kind of sacrifice by the poor heroine. The second flaw is Lehár’s. He purposely did away with some of the clichés of operetta. There is no second couple that takes care of our comic relief and has some pop melodies to sing in contrast to the more operatic fare of the tenor and soprano. But even here Lehár stays with the obligatory short third act where nothing of musical substance happens. And the third flaw is nobody’s fault. The first Goethe was Richard Tauber (“I don’t sing operetta, I sing Lehár”) and he often co-composed his arias together with the man he called his brother without a blood tie. They are so well-tailored to Tauber’s voice and the tenor himself was such a giant of belcanto that it is almost impossible to follow in his tracks. Some of these melodies are so etched in our memory with Tauber’s voice that even the best of his successors sound a little bit out of place when they try to sing Friederike.

Still there is almost an embarrassment of melodic ideas in the score. In the first act there is the wonderful first aria of Friederike (“Gott gab einen schönen Tag – God gave a beautiful day”) celebrating springtime. Then the students enter and they sing Goethe’s poem “Mit Mädchen sich vertragen – Meeting girls”, already composed by van Beethoven, though less lustily. Then the theatre Goethe makes his appearance as by that time the première public was probably already clamouring for Richard Tauber. He too has a fine and inspired slow walz to sing “O so schön, wie wunderschön – Ah, how beautiful” which is an ode to nature and the idyllic surroundings of Sesenheim (Werther’s entrance aria “O nature” in Massenet’s opera tells the same story). Then there is a short love duet between tenor and soprano inspired by another of the great German’s poems.

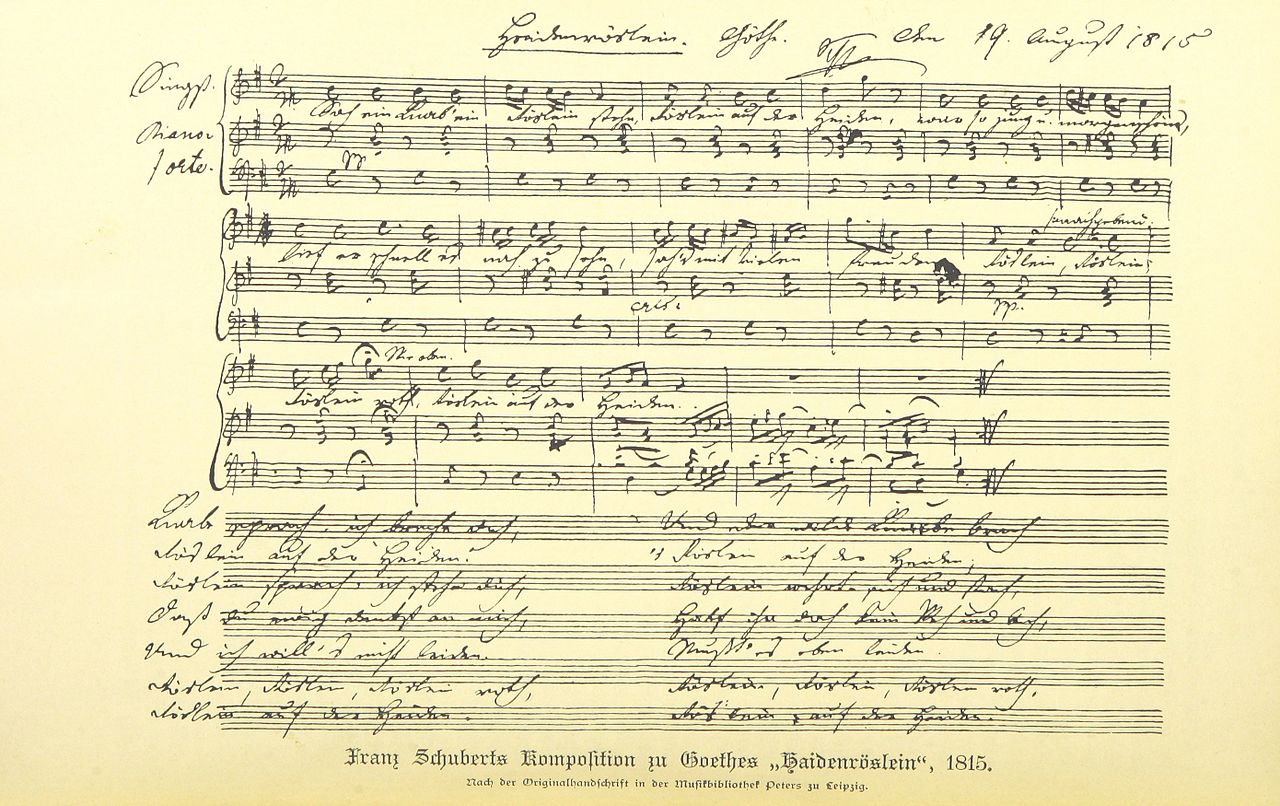

Franz Schubert’s famous version of the “Heideröslein”, 1815.

But the great challenge for Lehár was the composition, word for word, of the famous Goethe-poem Heideröslein. Every educated German knew by heart the famous rendition of Franz Schubert. Lehár succeeds triumphantly in finding authentic melodic inspiration which can compete with Schubert’s. It is no co-incidence that this second aria for Tauber was picked up for recording by other tenors as well. After some introductory music in the second act it is time for the big moment in Lehár’s later output: the Tauberlied (most famous = “You are my heart’s delight”) often composed in narrow collaboration with the tenor himself. This “O Mädchen, mein Mädchen – Oh maiden, my maiden” is one of Lehár’s very best: an unforgettable memorable tune in 6/8 without any cheap trick and the leitmotiv of the work. Tauber’s famous record is unsurpassed but the melody is so irresistible that many a great tenor (Konya, Wunderlich among others) have recorded it and failed honourably. Moreover the text is derived from an authentic love song for Friederike Brion: the sixth strophe of Goethe’s Mailied (Maysong). But the soprano has her big moment too with the magnificent (operatic) aria “Warum hast du mich wachgeküsst – why did you kiss me awake”. Of the many recordings none can compare in beauty and passion with Lucia Popp’s 1988 version.

The lover’s quarrel starts with a broken E major chord and the duet goes over in yet another Tauber aria “Liebe seliger traum – Love, wonderful dream” that ends in despair with “Oh! Geh nicht von mir -Don’t leave me”. The third act has a short solo for Friederike, a lovely duet between Lenz and Salomea and a few sentences by Goethe. I’ve always regretted that Lehár didn’t keep that moving “Liebe seliger traum” for the final of Friederike. Now the piece ends with a violin slowly repeating “O Mädchen, mein Mädchen” before the curtain falls on a fortissimo chord in C major.