Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

19 June, 2018

When Eduard Künneke presented his syncopated Der Vetter aus Dingsda in Berlin 1921, it was quite revolutionary to have so much American ‘jazz’ infiltrate German operetta. The foxtrot-and-tango sound Künneke created, with a heavy dose of banjos, pointed the way to Kurt Weill and Paul Abraham, and to all that was ‘modern’ in 1920s operetta. Vetter was a smash hit, and remains one of the most popular titles in the German repertoire system. When Künneke premiered Herz über Bord 15 years later at the opera house Zurich, again with a small-scale cast of two ladies and two gentlemen falling in love with the ‘wrong’ partner under unlikely circumstances that involve a lot of inherited money, the syncopations in the score were not novel anymore, but they still had a revolutionary sting. Because in the meantime the Nazis had come to power and had declared the American jazz influence ‘degenerate.’ Even though such things were now highly suspicious Künneke presented a top score of stuffed trumpets, accordions, saxophones and banjos, and offers some of the most bouncy music he ever wrote. The music had a career in Nazi Germany, too, even though the Jewish collaborators remained unnamed there. After Zurich Herz über Bord was seen in Düsseldorf, Dresden, Augsburg, Mannheim, Chemnitz, Dessau, Stuttgart, Breslau … and eventually even at Berlin’s Theater am Nollendorfplatz where Vetter had once premiered. The complete show has now been released by Capriccio, based on a 2017 Cologne radio performance conducted by Wayne Marshall.

The Capriccio recording of “Herz über Bord” based on a 2017 WDR production.

Herz über Bord tells the story of a champion swimmer called Lilli (remember: the world premiere in 1935 was only one year ahead of the famous Olympic Games in Berlin). This ‘Aryan’ wonderwoman inherits a fortune of 50,000 Marks from her uncle, but under the condition that she marries her childhood friend Hans, an architect who lives next door and comes to visit regularly by climbing over the roof. Hans is engaged to the eccentric actress Gwendolin, Lilli has promised herself to the somewhat dull and anti-heroic bank assistant Albert. In order to not lose the money, all four agree that Lilli and Hans should get married for a year, then divorce, and return to their old spouses. Together, they go on a honeymoon cruise where – slowly but unavoidably – the newly arranged couples fall in love, Lilli with Hans and Gwendolin with Albert. It’s a perfect screwball comedy. At the height of amorous complications, Hans leaves the cruise ship on a boat because he doesn’t dare tell Lilli what he really feels. When Lilli reads his farewell letter (that explains everything) she jumps over board – she’s a champion swimmer after all. And goes after Hans. In the last act, the four protagonists are in an Italian fisherman’s village, and all agree that the new arrangements suit everyone quite well. So the inheritance stays with Lilli and Hans, and Gwendolin stays with the financially solid Albert. Happy End.

Composer Eduard Künneke.

You can easily hear the new Nazi influences in this story: it’s thoroughly ‘German’ (set in a German town in 1935, as the libretto states), it presents the new ‘Germanic’ types (champion swimmers, architects, bank assistants), and it advocates a new ideal of women giving up their promising careers (as swimmers) once they are married; the man (in this case: an architect) earns the money by building a new Germany. It’s pretty straight forward propaganda for the new regime and its ideals, and it’s reflected in the sometimes banal lyrics by Kurt Schwabach and Max Bertuch. (Their name was later erased and substituted by Eduard von der Becke.)

Librettist Kurt Schwabach (left) with Willy Rosen in the 1920s.

To make this story work, you need a screwball director like Ernst Lubitsch, and you definitely need actors and actresses who can turn such a script into fun. German film operettas of the 1930s were full of such people, even in Nazi times. And talking of film operettas: there is a heavy dose of Werner Richard Heymann’s ‘Schlager’ style in Herz über Bord, e.g. when Hans come over the roof and through the window into Lilli’s apartment, singing “Hallo! Hat mich jemand gerufen, Ja, ich brauch’ keine Stufen, komm direkt übers Dach.”

The Cologne radio station WDR has cast their Herz über Bord with four young opera singers. And even though they all possess adequate voices, they rarely sound ‘fresh’ and they certainly don’t come across as screwball characters. They sing, and that’s it; there is no attempt at characterization or acting. And that makes the marvelous music somewhat tiresome. It should lift you off your seat, especially when Künneke goes into rhythmic overdrive (as he does in the comedy duets between Gwendolin and Albert). On the other hand, the romantic longing so perfectly captured in duets such as the slow waltz “Wenn das Herz auch bricht”(“Even when the heart breakes”) or Lilli’s song “Einmal kommt die Stunde” (“One day the moment will come…”) needs more sensuousness than Annika Boos as Lilli and Martin Koch as Hans can offer.

I found the other two leads, Julian Schulzki as Albert and Linda Hergarten as Gwendolin more convincing, they certainly have the catchier tunes.

For this production, WDR attempted to reconstruct the (lost) score and restore the original ‘jazz’ qualities. As conducted by Wayne Marshall the sound is not particularly jazzy, more 1950s swing. That unmistakable Künneke flair – which many will know from Vetter aus Dingsda, but in a large orchestral version also from his Tänzerische Suite 1929 – is never fully spot-on. Which is most noticeable in the “Intermezzo” that mixes Gershwin influences with Tänzerische Suite glory. Originally, it was inserted after the 3rd tableau, i.e. after Lilli jumps off the ship to catch up with her lover. On this CD, the intermezzo is presented as a kind of appendix, after the final scene.

The producer – Künneke expert and biographer Sabine Müller – claims this was done for ‘dramaturgical reasons.’ I don’t find this too convincing. She also points out that some numbers in the score – such as “Hallo, hat mich jemand gerufen” and “Bin leider nur ein Piccolo” were written by conductor Franz Marszalek; which doesn’t make them any less effective. (On the contrary.)

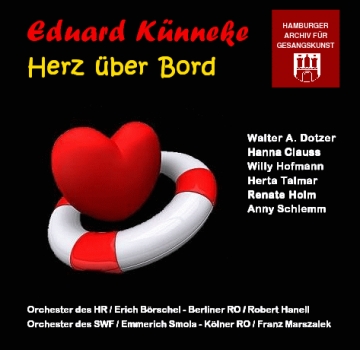

There is a highlight version of Herz über Bord available, conducted by Franz Marszalek, with Anny Schlemm among the lovers and with the Kölner Rundfunkorchester. The Hamburger Archiv für Gesangskunst has (illegally) released it on CD, together with so many other historic goodies.

Hightlights from “Herz über Bord” released by Hambruger Archiv für Gesangskunst.

The ideological undercurrent of the show is fascinating, especially today when the whole question of operetta from Nazi times is being examined more closely. I personally would love to see Herz über Bord in a proper screwball production with four singers/actors who are stronger character types. (Neuköllner Oper did a chamber version in 2002, directed by Heidi Mottl, with a completely re-written libretto which was fun, but not as historically interesting as the original version.)

This new Capriccio CD is a great opportunity to hear the complete (!) score and not just highlights. There is no libretto included in the booklet, but the plot summary and intro by Sabine Müller are translated into English.

And if you want to hear a truly ‘melting’ version of “Wenn das Herz auch spricht” then try Rudi Schuricke with the Operettenorchester Franz Marszalek; it’s wonderful and everything the young WDR singers are not – daring to be kitschy and sentimental. Also, the rubati and sudden stops/accelerandi Marszalek inserts should have been a role model for Wayne Marshall, but they obviously were not.

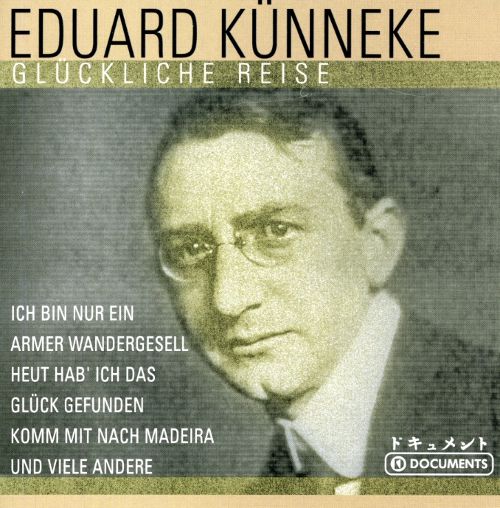

The compilation “Eduard Künneke: Glückliche Reise” by TIM (The International Music Company), 2003.

This Schuricke track is included on the compilation Eduard Künneke: Glückliche Reise. On that disc you also get to hear two sections from Tänzerische Suite conducted by Otto Dobrint who is even more spectacular than Künneke conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. And that’s saying quite a lot. Though Künneke’s own version is pretty outstanding too – pointing the way to what Herz über Bord should sound like, in the best of all possible worlds.

Thank you, this is very helpful.

I have streamed this album today and compared it with the concert version that was broadcasted by the WDR in 2015 and there are some differences:

The Broadcast was recorded live during a concert in Cologne (19.06.2015) and contains dialogue and one or two additional numbers (e.g. a blues in tableau 3). The Intermezzo is performed at the right place between tableau 3 and 4.

The interesting thing is, that the live performance, especially in connection with the dialogue, to me sounds much more inspired and vivid than the (studio?) recordings released by Capriccio.