Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

16 July, 2018

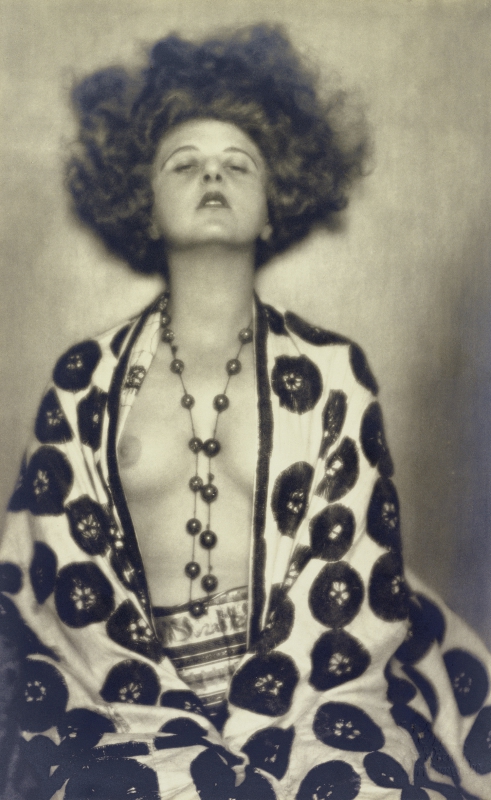

Ah, yes: Madame D‘Ora! She’s been one of my great operetta heroines, ever since I first found her portrait of soubrette Elsie Altmann, a photo taken shortly before Miss Altmann starred as Lisa in the original production of Emmerich Kalman’s Gräfin Mariza at Theater an der Wien in 1924. A Viennese newspaper used this particular photo to advertise the upcoming Kalman show, and remarked that Miss Altmann “rejuvenates” the category of the soubrette. She certainly made it look – with the help of Madame D‘Ora – scandalously modern. And I’ve always marveled at how up-to-date a Kalman soubrette looked back then, especially when compared to the standard operetta soubrettes on offer today. (Think, for example, of the new Gräfin Mariza at the Mörbisch festival. It looks positively Stone Age old fashioned next to Altman/D’Ora.)

MADAME D’ORA (DORA PHILIPPINE KALLMUS), Elsie Altmann-Loos, 1922 ATELIER D’ORA © Photoarchiv Setzer-Tschiedel / IMAGNO / picturedesk.com

Now, the Leopold Museum in Vienna has dedicated an entire exhibition to Madame D‘Ora. It’s entitled Make Me Look Beautiful, Madame D’Ora! The press release states:

“In her studio, d’Ora captured the great names of the 20th century’s world of art and fashion, aristocracy and politics. The first artist photographed by her was Gustav Klimt in 1908, the last Pablo Picasso in 1956. She further immortalized Emperor Charles I of Austria and members of the Rothschild family, Coco Chanel and Josephine Baker as well as Marc Chagall and Maurice Chevalier. In 1907 Dora Kallmus was one of the first women in Vienna to open a photographic studio. Within only a few months, the Atelier d’Ora had established itself as the most elegant and renowned studio for artistic portrait photographs and her images were widely disseminated through numerous newspapers and magazines in Austria and abroad. In 1925 an offer from the fashion magazine L’Officiel brought d’Ora to Paris, which became the center of her personal and professional life. She received countless commissions from fashion- and lifestyle magazines, which only started to abate from the mid-1930s when the political situation across Europe became increasingly precarious. A disenfranchised Jew, d’Ora lost her Paris studio in 1940 and for years had to hide from German occupying forces in France. Having narrowly escaped capture, the portraitist of society focused her at once sharp and empathic gaze after 1945 also on nameless concentration camp survivors as well as on the meat stock of the Parisian abattoirs. D’Ora’s work traces a unique arc from the last Austrian monarch, via the glamour of the Paris fashion world in the 1920s and 30s to a Europe entirely changed after World War II.”

ATELIER D’ORA | Maurice Chevalier | c. 1927 © Photoinstitut Bonartes, Vienna

The exhibition is created in cooperation with the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg as well as the Photoinstitut Bonartes in Vienna and is curated by Monika Faber and Magdalena Vukovic.

There is a catalogue, published by Brandstätter, with wonderful lesbian painter Tamara de Lempicka on the cover.

ATELIER D’ORA | Tamara de Lempicka with a hat of Rose Descat | 1933 © Private collection, Vienna

All of these pictures are a reminder of how contemporary operetta and the people involved in the art form once were, and how in tune with modern times. It’s a great pity that this link between operetta and the avant-garde has been lost in the post-WW2 years and that present day operetta ‘makers’ in Austria are so absolutely not interested in bringing these worlds together again. Just take a look at the Volksoper offerings, not to mention Baden bei Wien, Ischl, and Mörbisch.

Rinnat-Moriah as Lisa and Christoph Filler as Kolomán Zsupán in “Gräfin Mariza” at Seefestspiele Mörbisch, 2018. (Photo: Seefestspiele Mörbisch/Jerzy Bin)

Perhaps the Leopold Museum should send invitations to the artistic directors of all the above mentioned theaters/festivals, and re-introduce them to Elsie Altman and Maurice Chevalier, or Josephine Baker. They all represent ‘operetta’ as it should and could be today, instead of the stuffy ‘traditional’ approach that has nothing to do with any real operetta ‘tradition.’ It’s just tacky. An embarrassment to the genre, plus, in this case, to the memory of Emmerich Kalman.

For more information, click here.