Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

12 February, 2019

Let’s start this review backwards, shall we? The last sentence in Peter Hawig’s new book for the Offenbach bicentenary is: ‘Offenbach makes you happy.’ Ah, yes…. of course he does. What Hawig means is the immediate effect of the music: ‘No musical or discourse analysis – however deep it might be – and no thorough historic, biographical or comparative research can substitute for the enjoyment the music offers, or the immediate joys of a stage experience.’

“Musiktheater als Gesellschaftssatire. Die Offenbachiaden und ihr Kontext” by Peter Hawig and Anatol Stefan Riemer (Musikverlag Burkhard Muth, 2018)

That may be so. But the stage experience, and many purely acoustic Offenbach experiences, heavily depend on how the interpreters understand and present ‘operetta.’ Thus it’s of the greatest relevance what researchers such as Peter Hawig and his many affiliates bring into circulation. In an ideal case, they arouse interest to look at Offenbach and his singular form of musical theater with new eyes and ears, stimulating new forms of performance.

No one believes this to be more necessary than Mr. Hawig himself. He has bemoaned the current state of performance practice many times over, here he writes: ‘It’s like two millstones around Offenbach’s neck that he’s connected to the gemütlich and kitsch-laden Viennese Operettas (especially of the 20th century) on the one hand, on the other to the world of Moulin-Rouge and Montmatre cabarets, the “French Cancan” as Toulouse-Lautrec painted it, and to the “Valse chaloupée” danced by Mistinguette and Max Dearly. Such a way of interpreting Offenbach is wrong ["derlei Rezeptionsmuster gehen fehl"], but they are very persistent.’

Poster depicting can-can dancers by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 1895.

Mr. Hawig advocates a different Offenbach style, and he wants to put a different type of Offenbach image into our heads. Because Offenbach should never be: ‘vulgar.’ He writes in his new book that ‘one thing was definitely frowned upon ["verpönt"] in performances – vulgarity. Hortense Schneider experienced this when she sang the couplet from Périchole in the act 2 finale, about the stupid men, with a “timbre [...] extrêmement populacier” and infuriated ["gegen sich aufbringen"] the auditorium.’ [Never mind that we have very different reports on La Snédèr from London where The Era reports on her vulgarity and the appreciative reaction of the upper class audience, quoted at length in Kurt Gänzl’s Emily Soldene – In Search of a Singer.]

Emily Soldene as Offenbach’s Helena.

Ten years ago Hawig translated and edited the essays of Robert Pourvoyeur ‘to rehalilitate the composer.’ They came out at Musikverlag Burkhard Muth. There, too, many books by Hawig’s followers appeared, all driven by the same goal of rehabilitating Offenbach. Hawig’s own book Die Offenbach-Renaissance findet nicht statt from 2014 points in the same direction. And now Musiktheater als Gesellschaftssatire. Die Offenbachiaden und ihr Kontext states: ‘The true time of the Offenbachiade seems not to have arrived yet.’ (“Die eigentliche Zeit der Offenbachiade scheint noch immer nicht gekommen zu sein.”)

It’s as if we are waiting for that day like others await the Messiah or Judgment Day, the day on which the faithful will be separated from the sinners, which in Hawig’s view of the world means: the terribly kitschy 20th century Vienna style operettas will sink into the abyss and Offenbach rises like phoenix once more and reigns supreme. He will not only do so with his satirical and parodist Offenbachiades, but also with his ‘real’ and ‘worthy’ operas. Because it’s obviously the aim of Mr. Hawig to elevate all of Offenbach’s musical theater to the higher regions of opéra comique and make Offenbach the father of true comic opera. That’s what drives the author to examine the ‘Erinnerungsmotive’ (a kind of Leitmotiv or memory motive technique) and the harmonic structures of the 13 works he classifies as ‘Offenbachiade.’

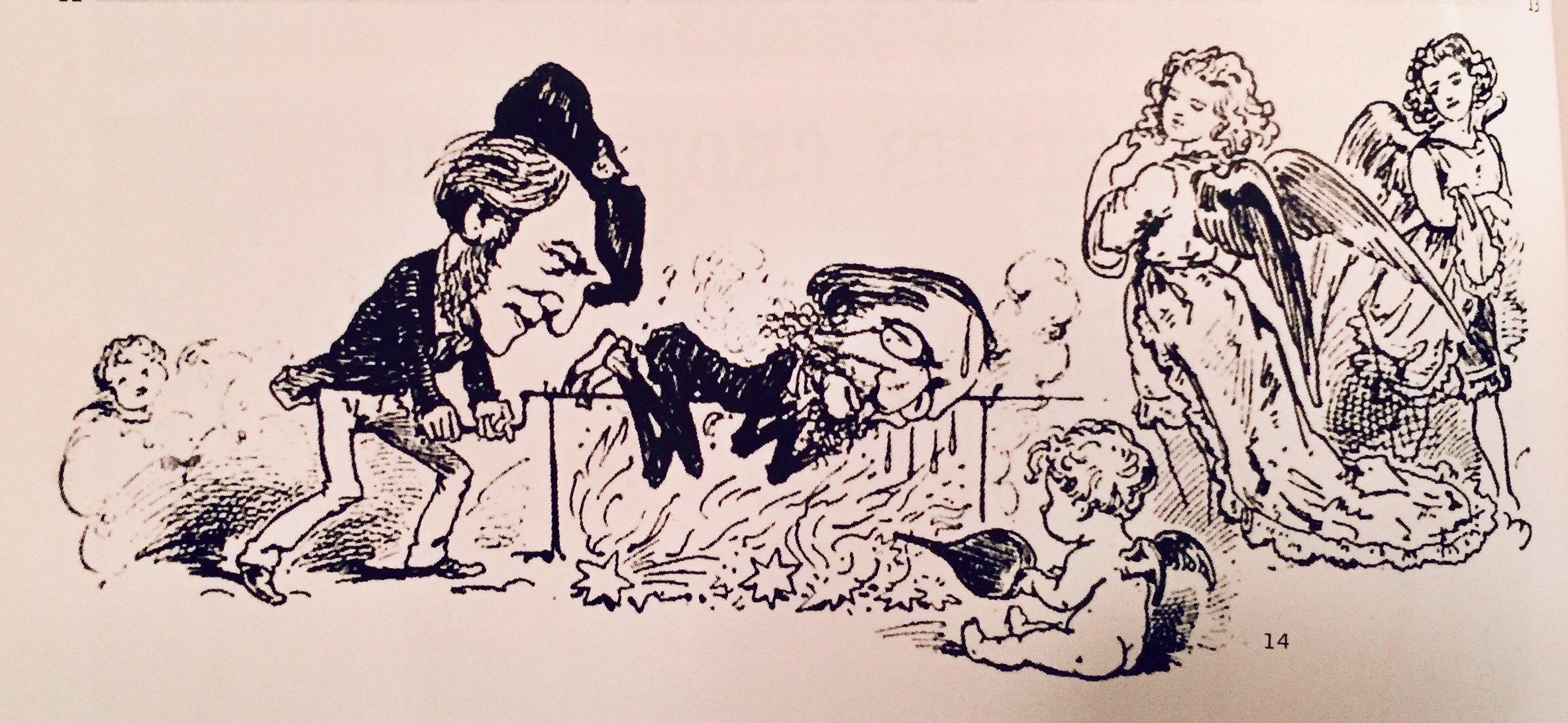

Richard Wagner finishing off his competitor Jacques Offenbach, a charicature from the 1870s, after the Prussian-French war.

These are, in case you are wondering: Ba-Ta-Clan, Orphée aux Enfers, Geneviève de Brabant, Le Pont des Soupirs, La Belle Hélène, Barbe-Bleue, La Vie parisienne, La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein, Le Château à Toto, L’Île de Tulipatan, La Périchole, La Princesse de Trébizonde and Les Brigands.

The protagonists of Offenbach’s “Ba-ta-clan” awaiting their execution; original 1855 production.

By examining the harmonies and memory motives in these works it becomes clear – in the gospel according to Hawig at least – that they are not mere ‘operettas’ but close in style and construction to the operas the composer wrote – culminating in the Tales of Hoffmann.

I could say a lot about the attempts of the author to define ‘Offenbachiade,’ often in excruciatingly banal ways. (For example: there must be ‘a recognizable relation of the plot to current social happenings’ or ‘a satire of the imperial system,’ and ‘an ecstatic invocation of wine, dance and eros.’)

Gustave Doré’s vision of the „Galop infernal“, as seen 1858 in Paris.

It’s especially ‘eros’ as a central component of all Offenbach’s musical theater that Mr. Hawig has difficulty with. The fact that nearly each and every contemporary review talks about the moral questionability of Offenbach’s works, their indecency, their groveling in a low depth even below decency, their hurtfulness to the modesty of the audience etc. is not discussed here. Nowhere. Even though Laurence Senelick recently remarked in his brilliant Offenbach study: ‘Like “French,” “Offenbach” could be applied as shorthand for a range of eroticized performances.’

Mr. Hawig circumnavigates these aspects as widely as possible.

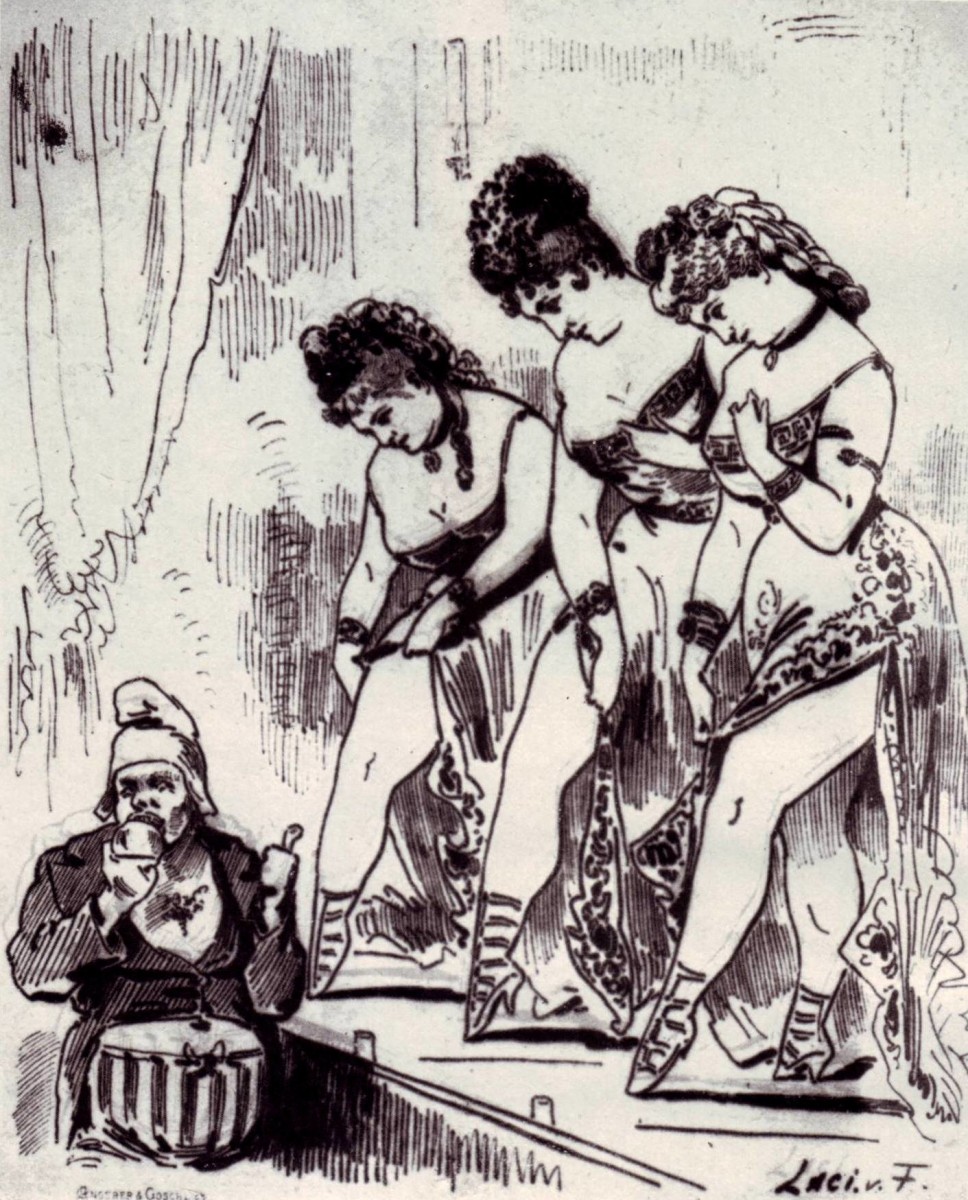

Three Helenas in Vienna, showing off their legs to the theater director in the 1860s.

This becomes strikingly evident in the chapter on Offenbach popping up in novels (“Belletristik”). Hawig lists an impressive number of works, from Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks and Zauberberg to Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, he also mentions the Portuguese novel Os Maias, O Primo Basilio, O Mandarim, A Tragédia de Rua das Flores by José Maria Eça de Queiroz. Karl Kraus’ Die letzten Tage der Menschheit is included in the list, as is Wolfgang Quetes’ Frère Jacques about Offenbach‘s brother Jules.

The one title you’ll search for in vain is Émile Zola’s Nana – which is a novel Hawig’s disciple Ralf-Olivier Schwarz quotes, at length, in his brand new Jacques Offenbach. Ein europäisches Porträt.

Ralf-Olivier Schwarz’ “Jacques Offenbach. Ein europäisches Porträt.” (Böhlau Verlag, 2018)

He does so in the context of performance practices in Paris in the 1860s. And while Mr. Schwarz quotes almost a full page from the novel, to describe the atmosphere and audience in the Théâtre des Variétés, he stops just before we get to the notorious scene in chapter 1 in which Nana appears on stage as a blonde Venus, reminiscent of Hortense Schneider as the blonde daughter of Venus, Helen of Troy:

‘A shiver went round the house. Nana was naked, flaunting her nakedness with a cool audacity, sure of the sovereign power of her flesh. […] Her Amazon breasts, the rosy points of which stood up as stiff and straight as spears, could be […] clearly discerned […] beneath the filmy fabric. […] And when Nana raised her arms, the golden hairs in her arm-pits could be seen in the glare of the footlights. […] The men’s faces were tense and serious, their nostrils narrowed […]. All of a sudden, […] the woman stood revealed, a disturbing woman with all the impulsive madness of her sex, opening the gates of the unknown world of desire.’

Mr. Schwarz also leaves out the comment of the director of the Théâtre des Variétés claiming his venue is a brothel. Zola later describes in detail what that means when Nana meets the Prince of Wales, just like Hortense Schneider did in real life.

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Painting by Edmond Morin.

It’s astonishing that Ralf-Olivier Schwarz should think these aspects unimportant and not worthy of mentioning. Mr. Hawig goes one step further and doesn’t mention the book at all.

Probably because such themes don’t fit with his efforts to ennoble Offenbach. And maybe because Offenbach is not explicitly mentioned by Zola, even though Laurence Selenick points out that of course it’s all about Offenbach in the Zola novel. And Mr. Senelick includes the nudity and the opening of the gates of the world of desire. (Perhaps German researchers at music schools are too timid for this kind of discourse, fearing what their young students might think – of them?)

President Grant and Jim Fisk watch “La Périchole” at the Fifth Avenue Theater in New York, 1869. As shown in the “Illustrated Police Gazette.” (From: Laurence Senelick, “Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture,” 2018)

To brush aside any discussion of such a ‘vulgar’ side of Offenbach, and the audience appreciation of it, Mr. Hawig inserts a chapter called ‘Audience and Marketing’ [“Publikum und Vermarktung”]. There, he claims there ‘is no sociological research about Offenbach’s audience,’ and that here – in this book – he ‘cannot make up for that.’ As a result, all statements about the original Offenbach audience have ‘something vague about them’ [“haben etwas Ungefähres an sich”].

He admits that we know about ticket prices for the Bouffes Parisiens, which were high, but a ‘little burgher’ [“kleiner Bürger”] could visit the cheaper seats which existed in the upper region of the house. However, an ‘untrained blue-collar worker could not afford to do this,’ as he earned 750 Francs a year and a ticket at the Variétés cost up to 6 Francs. That’s where Belle Hélène and Gerolstein played, that’s also where the Prince of Wales met Miss Schneider.

Mr. Hawig goes on to quote quite a few sources describing the theater situation, how the air in the auditorium ‘was pregnant with perfume and sensual women,’ as journalist Friedrich Uhl writes about his visit to the Bouffes Parisiens to see Orphée aux Enferns. ‘Many men were also wearing make-up in Paris back then. […] It was a delectation for Parisians of the Third [sic] Empire to go there after dinner and sit in the small space with the deafening noise of the music erupting into the cancan, with the skyrocketing limbs of the maenads, the hoarse laughing [“Wiehern”] of the audience, a cross-fire of looks up to the stage and back down to the stalls.’

The ladies at Offenbach’s new theatre Bouffes-Parisiens.

But even his own sources don’t offer ‘valid data.’ Thank God there are some that claim Offenbach wasn’t just for the ‘happy few’ [“besseres Publikum”], but also for people from the ‘middle classes,’ such as Offenbach’s collaborators Halévy and Meilhac, Crémieux et al. Also, there was a ‘young spirited and witty audience looking for amusement that valued references, piquancy, and ecstasy.’

In the end it probably boils down to this: Mr. Hawig wants to be a potential member of that original audience. But not by elevating his own social status, but by downgrading that of 19th century visitors as described by himself and others. (Mr. Hawig is an ‘Oberstudienrat’ at the Bischöfliches Fürstenberg-Gymnasium in Recke/Westphalia, certainly not a blue-collar worker.)

Cover of “L’Eclipse” 1868 with cartoon by Gill of Dupuis and Hortense Schneider in Offenbach’s “Barbe bleue” at the Variétés theater.

While I was greatly irritated by the lack of inspiration in the analysis of the various works (Volker Klotz, by comparison, is on an entirely different intellectual level), there is one real knock-out moment on page 489. After Mr. Hawig has brushed aside all attempts by Johann Strauss to write an ‘Offenbachiade’ (Der lustige Krieg and Fledermaus), Hawig proclaims: ‘In a few important works Viennese operetta can claim to be a worthy successor of comic opera composers such as Lortzing and Nicolai.’ ["In einigen bedeutenden Hervorbringungen aber kann die Wiener Operette den Anspruch als Nachfolgerin der komischen Oper Lortzings oder Nicolais durchaus einlösen."]

Mr. Hawig explicitly mentions Suppé’s Boccaccio in this context, as well as Millöcker’s Bettelstudent and Genée’s Nanon, die Wirtin vom Goldenen Lamm.

A German postal stamp from 1951 with Albert Lortzing’s portrait.

The fact that Mr. Hawig quotes Nazi ideology/ideals here, almost word for word, is deeply disturbing. As a reminder: Hans Severus Ziegler, the man who initiated the exhibition Entartete Musik/Degenerate Music, wrote in the 1939 Reclams Operettenführer that the ‘tasteful and musically cultivated operettas of older and modern times’ should be combined with the ‘comic Spielopern’ of Lortzing, because their ‘lightness and true humor’ [“Leichtigkeit und wirklich[e] Humorigkeit”] will have an ‘educational effect on the tastes of the audience’ whose ‘sense of style and entertainment should not degenerate further.’ Alongside Ziegler’s “Zum Geleit!” is Walter Mnilk’s essay “Die geschichtliche Entwicklung.” Mr. Mnilk singles out – coincidentally? – the exact same ‘Viennese’ titles that Mr. Hawig describes as ‘worthy’ Spielopern successors.

So is Lortzing what all ‘real’ comic opera – and Offenbach performances today – should strive for?

Let’s not forget that the Nazis claimed ‘true’ operetta was a Viennese invention by Suppé and Strauss, and that Offenbach and his ‘degenerate’ music was just an unimportant prelude. Are we making up for that, today, by putting Offenbach back into the picture and into the Lortzing/Nicolai tradition? (You could add Flotow here, if you wish.)

Lortzing’s “Undine” with Anneliese Rothenberger on EMI.

It’s been done before. After WW2 EMI recorded a full Lortzing series in the 1960s and 70s with the same ensemble that they produced a classic operetta series with, first Strauss and Millöcker, later also Offenbach.

Millöcker’s “Bettelstudent” in the EMI series, labeled “Weltstar Operette” with singers from the Spieloper ensemble.

These recordings are still in circulation and cement Mr. Ziegler’s ‘Operetta as Spieloper’ ideal long after the Nazis have disappeared. EMI also recorded French operettas with the same ensemble they recorded an opéra comique series with, more or less applying the same principles as with Lortzing.

The EMI recording of Offenbach’s “Orpheus in der Unterwelt” with Anneliese Rothenberger.

Where does that leave things? This latest release in the series ‘Jacques-Offenbach-Studien’ by publisher Burkhard Muth is a rather unattractively packaged book that will probably land on the shelves of various German university libraries. Whether students there will be inspired to look at Offenbach in a novel way after reading these pages is doubtable. Mildly put.

“Jacues Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture” (2018) by Laurence Senelick, together with the ground breaking “Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters” (1999).

I can only hope that these libraries also have Laurence Senelick’s expensive Cambridge University Press publication on Offenbach. It offers more insight, it’s better written, and it has better pictures.

German language operetta and Offenbach research should take that as a role model, instead of constantly going around in circles with their ennoblement crusade. Since when is Lortzing such a hot ticket, I cannot stop wondering? Here’s his famous wooden shoe dance from the Dutch themed Zar und Zimmermann:

Straight ahead to new horizons would be a more worthwhile route, in my opinion, the necessary cues for new paths are there in front of everyone’s eyes, in Senelick’s book, in Offenbach und die Schauplätze seines Musiktheaters, and in the Yon biography. All you have to do is grab them by the balls. (Metaphorically speaking.)

Josefine Gallmeyer in “Die Prinzessin von Trapezunt,” Vienna. (Photo: Fritz Luckhardt / Sammlung Theatermuseum Wien)

Some conductors and stage directors have already done so, e.g. Adam Benzwi who is in the midst of preparing a new Princesse de Trébizonde together with Max Hopp, completely without Albert Lortzing and Otto Nicolai associations. Instead, they have hunky musical star Jan Rekeszus who could easily open ‘the gates of unknown desires,’ undressed on stage or not.

Barihunk Jan Rekeszus. (Photo: Dennis König Photographie)

Let’s see how his Princess and the audience react!