Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 July, 2018

It started out as a small concert performance at Schwules Museum in Berlin in the context of a Siegfried Wagner exhibition – and immediately attracted 200+ prominent guests. But that wasn’t the end of Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre, or An Operetta for Two Gay Tenors, a song cycle (and story) about two men in a relationship crisis that they solve in their own amusing way. This ‘operetta’ was written by award winning author Johannes Kram, who runs the highly political Nollendorf Blog and analyzes the LGBT situation in Germany, the music was written by Florian Ludewig. After the Berlin premiere they returned to Schwules Museum for the Lange Nacht der Museen in 2017 with two new tenors, performing in the context of the celebrated Winckelmann exhibition The Divine Sex, then went onto Stuttgart for a museum performance in the context a Patrick Angus exhibition. And from there the songs took on a life of their own. They were heard in many political talk shows, among them at Tipi am Kanzleramt (where Frau Luna was recently seen). The next outing will be at a discussion in Trier with current justice minister Katarina Barley. We spoke with Mr. Kram about his motives to create a modern day operetta instead of a musical comedy or something entirely different.

Blogger Johannes Kram (r.) and composer/pianist Florian Ludewig. (Photo: Dirk Lang)

You are a political activist and award winning political blogger. What on earth made you decide to write something as ‘old fashioned’ and out-of-date as an ‘operetta’ (for two gay tenors)?

A void is not necessarily political. But it is political to fill empty spaces. Storytelling advances emancipation. Hearing gay stories when and where we least expect them challenges us and the world around us. We know about gay literature, art and cinema and even gay perspectives in modern opera. But, how do we approach a genre like operetta, which more or less ended before ‘we’ as an LGBT+ community became visible? By creating a ‘normality’ that never existed at the time this genre was contemporary and often ahead of its time we can observe how this affects us and the environment we live in. We enter a space where we are still not officially ‘there,’ and we occupy that space. Sometimes you have to go back in order to move forward.That’s what I’m doing with Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre. And judging from the reactions so far, it works.

Poster for the “Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre” by Florian Ludewig and Johanns Kram.

Homosexuality has been part of operetta history from the mid-19th century. The first same sex marriage was discussed on Offenbach’s Island of Tulipatan, back in the 1860s, the first ‘gay’ character appears in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience in the 1880s. There are many gender bending and non-heteronormative stories in operetta. Yet homosexuality was never really addressed as a topic in operetta – because homosexuality was criminalized in many countries until the late 1960s. So the subject had to be ‘masked’. Today we can address it more openly, as was done by the authors of The Beastly Bombing in 2006. How do you present homosexuality in your operetta?

Actually, homosexuality is not really addressed. At least it is not the central point. It’s just there, without being a problem or special issue. This is the difference between many contemporary gay operas, which are produced in opera houses: opera always exhibits great suffering, and these works often present homosexuality as a challenge in itself. In contrast, operetta is about lightness, lust and love. It is also very funny and bouncy, it makes the audience feel like dancing. In opera, sex often leads to death, whereas in operetta you have sex-for-fun. There are problems, but the audience knows from the beginning that all problems will be solved by the end of the evening (unless it’s a Lehár operetta). Yes, this might be called ‘naive.’ But this naiveté is important. Straight audiences have always had all these good old love songs, those good old love stories. Our operetta shows the power of such a good old story, the power of old fashioned and familiar sounding songs that appeal to and resonate with us anew when we suddenly realize that we are the target group for many homophobic elements in society. In that sense, our show offers reconciliation: this is what could have been in the past, and it is an invitation to how it can be in the future.

Johannes Kram being interviewed by Rosa von Praunheim in front of the Brandenburg Gate, 2018, about the LGBT+ situation in Germany. (Photo: Dirk Lang)

Operetta music has always been popular music, mirroring the latest trends in pop culture. At least this was so while operetta was an alive and kicking art form, which it isn’t anymore. The authors of Beastly Bombing chose Gilbert & Sullivan as their stylistic role model. What is the music like your composer Florian Ludewig wrote?

Florian has written music that could be from the golden time of operetta. However, his music is progressive, just as the operetta genre in general has integrated new styles. His music allows you to be consumed by the world of operetta where, for a short period of time, you forget the world and everyday life. Florian has written new music, but it seems as if at its core his music is already present in our memory. We relate to it like we relate to pop music. It is what operetta music symbolized in its time: popular hit songs. Now, the story does not seem artificial, it suddenly seems quite normal that a contemporary story is linked to this kind of music.

The action is set in contemporary Berlin. Isn’t the party and club culture there dominated by other forms of music? And why set it in Berlin and not London, New York or anywhere else?

We deliberately placed the story in the tradition of Berlin’s operetta. Musically, because unlike the Viennese operetta it is not all about waltzes. It has waltzes but it also shows an exciting mix of other music styles. As for the subject there are, of course, amazing parallels between what happened here a hundred years ago and what Berlin stands for today: the colorful mix of minorities and walks of life. Through the Third Reich the free spirit of Berlin operetta was abruptly ended and with it the imagination of new forms of living together. Many of the Jewish or gay authors/composers had to leave the country. Some have successfully worked on Broadway or in Hollywood. But many lives were destroyed or lost. Many of these artists have at that time dared to do things that, from today’s point of view, seem brave and innovative. We want to remember that, too. Besides: We live here. We describe a city, we describe people that we know.

The world-premiere of “Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre” at Schwules Museum in Berlin, in the context of a Siegfried Wagner exhibition. (Photo: Schwules Museum)

The world-premiere of the concert version of the operetta happened at the Schwules Museum in Berlin. In the rooms of a Siegfried Wagner exhibition (a composer who could never express him homosexuality in his musical works). Why do you think such a museum is a fitting location for the premiere of your show? What were the reactions like (also towards such a genre as operetta)?

It had something magical, as there is actually no such kind of music with such kind of lyrics in modern musical plays. It triggered a lot of conversations about how gay life would be different, more self-conscious if we as gays were able to link our cultural childhood memories to gay stories like straights relate to straight stories. For many men of my generation, operetta is something we know from black-and-white or early color TV. Since that time, there are no well known new operettas, and therefore our operetta is linked directly to these childhood memories. Besides, the operetta is corny, there is no discourse, it shows, it captivates, it allows you to be carried away while connecting people and breaking down barriers. No education is needed. For a new German cultural project, in which heroic opera voices are performing, this is quite unusual.

Felix Heller sings the “Liebeslied von Mann zu Mann” in front of Brandenburg Gate at a LGBT+ demonstration, 2018. (Photo: Private)

How did you choose your singers, why did you choose them?

We were looking for artists who simply love the operetta, were interested in adding a new dimension to their performance and generally having fun doing it, who were interested in the emancipation aspect: what does it mean to be a ‘gay tenor’? Does the singer have to be gay? What makes the difference?

Tenors Matti Reiser and Ricardo Frenzel Baudisch rehearsing for the performance at Long Night of Museums in Berlin, 2017. (Photo: Private)

This is a unique situation, as there is no gay operetta, there are no role models; each artist creates something entirely new, different, plays with stereotypes, meets and destroys expectations. We have been looking for singers whose style and education are distinctive. But there is no formula. The most important thing is that the two performers create a contrast as well as harmonize. We are proud to have found great artists who have embarked on this endeavor. The viewers identified themselves very much with two roles, they love them. This may be because their own story is playing today. But, I think it’s mainly due to the fact that something on a very personal level.

The authors and singers at a performance of “Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre” at Kunstmuseum Stuttgart. (Photo: Private)

Will there be a lesbian or trans* version of your operetta too, one day, or is operetta exclusively linked to gay men and tenors?

Our project is about two tenors and the highlight of course is a tenor love song from man to man, something which does not exist in operetta history yet. I think there should not be a trans* or lesbian “version”. There should be new, unique pieces which reflect trans* and lesbian stories.

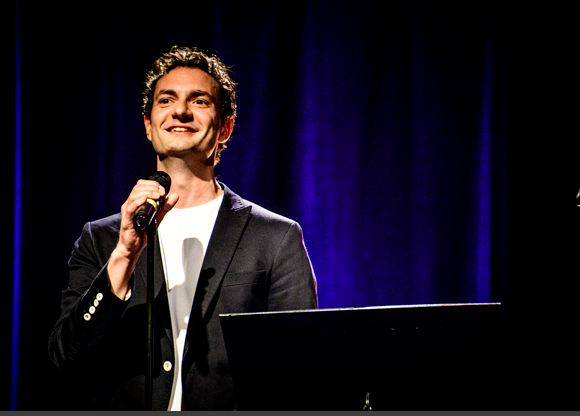

Ricardo Frenzel Baudisch performing “Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre” at Tipi am Kanzleramt in Berlin, 2018. (Photo: J. Jackie Baier)

I hope that future of operetta will be more inclusive and that more authors and composers will fall in love with operetta.

The singers of the world-premiere of “Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre” at Schwules Museum, 2017: Daniel Philipp Witte (l.) and Eric Rentmeister. (Photo: Private)

How interesting-bravo!