Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

26 April, 2017

For many operetta lovers, Austrian tenor and Volksoper star Peter Minich, is an icon. He certainly represents a very particular post-war operetta style that is well documented on record and film, or today on CD and DVD. The Stadtmuseum St. Pölten has dedicated a first full-scale exhibition to Minich who died in 2013. It is curated by the museum’s director Thomas Pulle. Additionally, operetta historian Hans-Dieter Roser has edited a catalogue on the life and archievements of Minich, filled with hundreds of fascinating photographs.

Peter Minich as a chorus boy at the Burgtheater. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

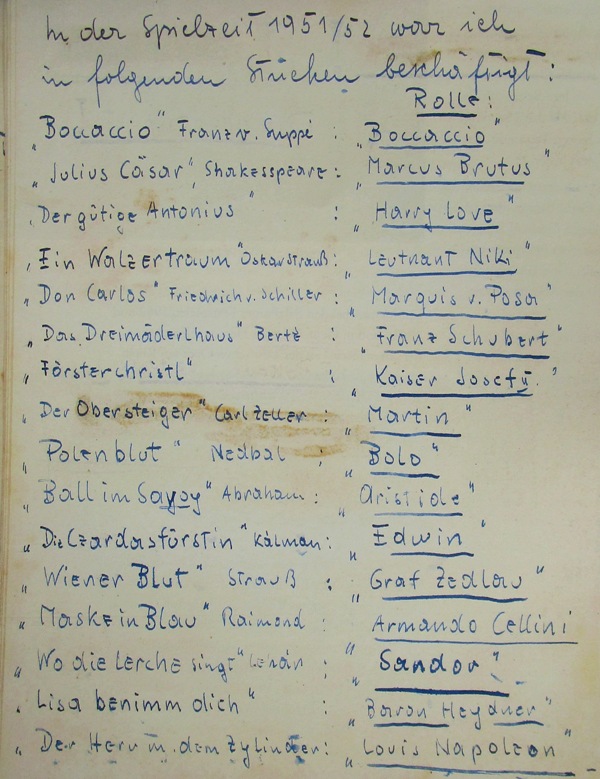

Minich was not your typical opera-singers-turned-operetta-star: he was, first and foremost, an actor. And only later became an actor who could also sing. And sing and act he did, first as a chorus boy at the legendary Burgtheater, then in St. Gallen and St. Pölten, where, at the local Stadttheater, he performed in Boccaccio, Ein Walzertraum, Dreimäderlhaus, Försterchristl, Obersteiger, Polenblut, Ball im Savoy, Csardasfürstin, Wiener Blut, Maske in Blau, Wo die Lerche singt – all in one season, 1951/52. That same season he also performed in Schiller’s Don Carlos as Marquis de Posa and in Shakespeares Julius Caesar as Marcus Brutus. Plus various other roles. We, today, can only marvel at such a multitude of titles that show how popular operetta was back then, and how eager post-war audiences where to rediscover many titles that had been taken off the program by the Nazis because they had been labeled “degenerate.”

A list of Peter Minich’s roles at the St. Pölten Stadttheater in 1951/52. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

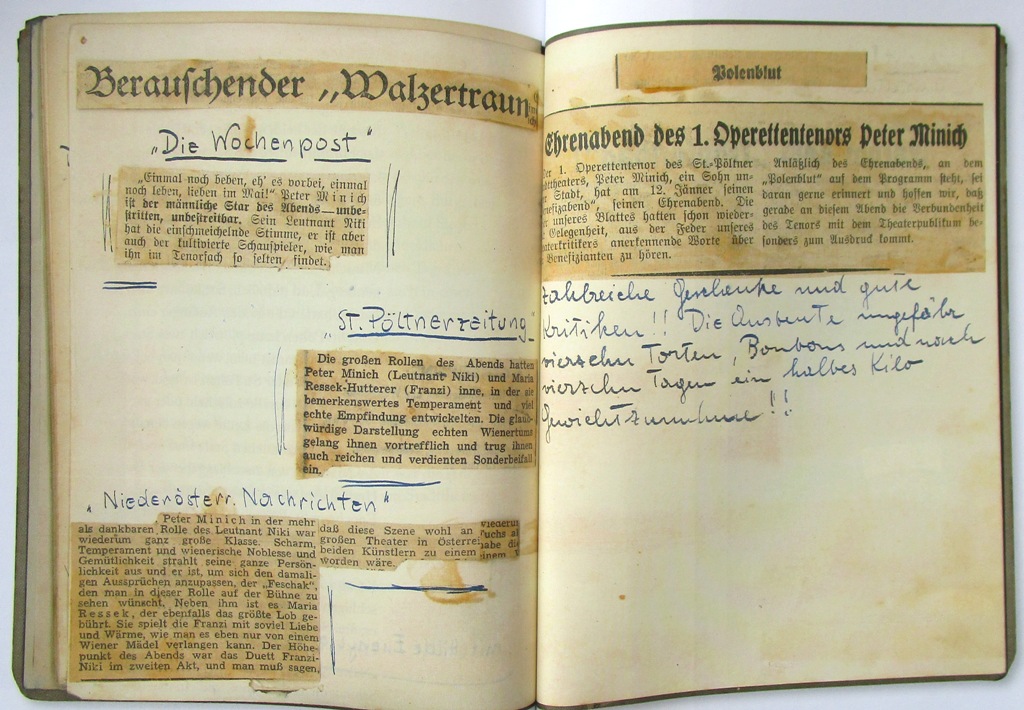

The catalogue chronicles the blossoming career of Minich with many historical photos, taken from the tenor’s private archive. He kept a detailed diary of all his reviews and performances. They document a performance tradition in the 1950s that is not very familiar anymore, overshadowed – even in Minich’s case – by the more glossy later TV images.

Peter Minich and Anneliese Rothenberger performing together on TV. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

Obviously, a star such as Minich appeared on Anneliese Rothenberger’s TV show. But this later form of operetta should not make fans forget that this is just another episode in the performance history of the genre, and in Minich’s life. And just like Minich and the Austrian operetta scene moved quite far ahead from the early 1950s to the 2000s (when Minich played Emperor Franz Joseph in Baden Baden, in Stolz’s Frühjahrparade), we have again moved ahead once more. Even if not everyone in the Austrian operetta world wishes to acknowledge that.

Peter Minich as Juan Damigo in Dostal’s “Clivia,” 1953. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

The 100 page catalogue is an important document, with a full register of all of Minich’s roles. And with a very personal essay by Hans-Dieter Roser who met Minich at the Volksoper and accompanied his career for many years. (The Volksoper is a sponsor of the St. Pölten catalogue.)

A double-page from Peter Minich’s diary, with reviews. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

The exhibition was initiated by Minich’s widow, Guggi Löwinger. As a star in her own right, she originally took the idea for such a show, coinciding with Minich’s 90th birthday, to the Theatermuseum Wien. Which is an obvious choice, considering the status of Mr. Minich in Austrian musical theater history. However, the Theatermuseum Wien turned down the project, claiming their schedule was already filled up. This is when Miss Löwinger contacted St. Pölten, the city where Minich was born, where he grew up, and where his career first took flight. In St. Pölten, the show turned out such a great success that there is talk of prolonging it. It can definitely be seen until May 14.

Peter Minich in “Die gold’ne Meisterin,” at the opera house Graz 1959. (Photo from the catalogue “Peter Minich. Ein Leben für die Musik.” Stadtmuseum St. Pölten 2017)

That the Theatermuseum Wien turned this show down is certainly their loss. Anyone who doesn’t have time to travel to St. Pölten can order the 18 Euro catalogue, sponsored by the Volksoper Wien, via the museum’s website and marvel – again and again – at the endless list of operetta roles, from Schröder’s Hochzeitsnacht im Paradies (1952) to Fred Raymond’s Geliebte Manuela (1954) to Stolz’s Kleiner Schwindel in Paris (1957), Leon Jessel’s Die golden Mühle (1958), Sullivan’s Mikado (1962) Loewe’s Gigi (1987) and Leo Fall’s Der fidele Bauer (2002). It’s a rich life in operetta, without any doubt. A richness sadly completely lost today – killed by performers such as Minich? (That would, indeed, be an interesting discussion: where and when did things go wrong?)