Enrique Mejías García

Glitter and be Gay: Reloaded (ed. by Kevin Clarke), Männerschwarm Verlag

17 March, 2025

In the new edition of the book Glitter and be Gay: Reloaded Spanish musicologist Enrique Mejías García writes about the 1923 zarzuela Benamor by Pablo Luna as his “gayest operetta moment.” In the book, this text is printed in a German translation. But because it’s a fascinating read, we give you this short essay in an English version by Christopher Webber, with permission from the author and from the editor of the book.

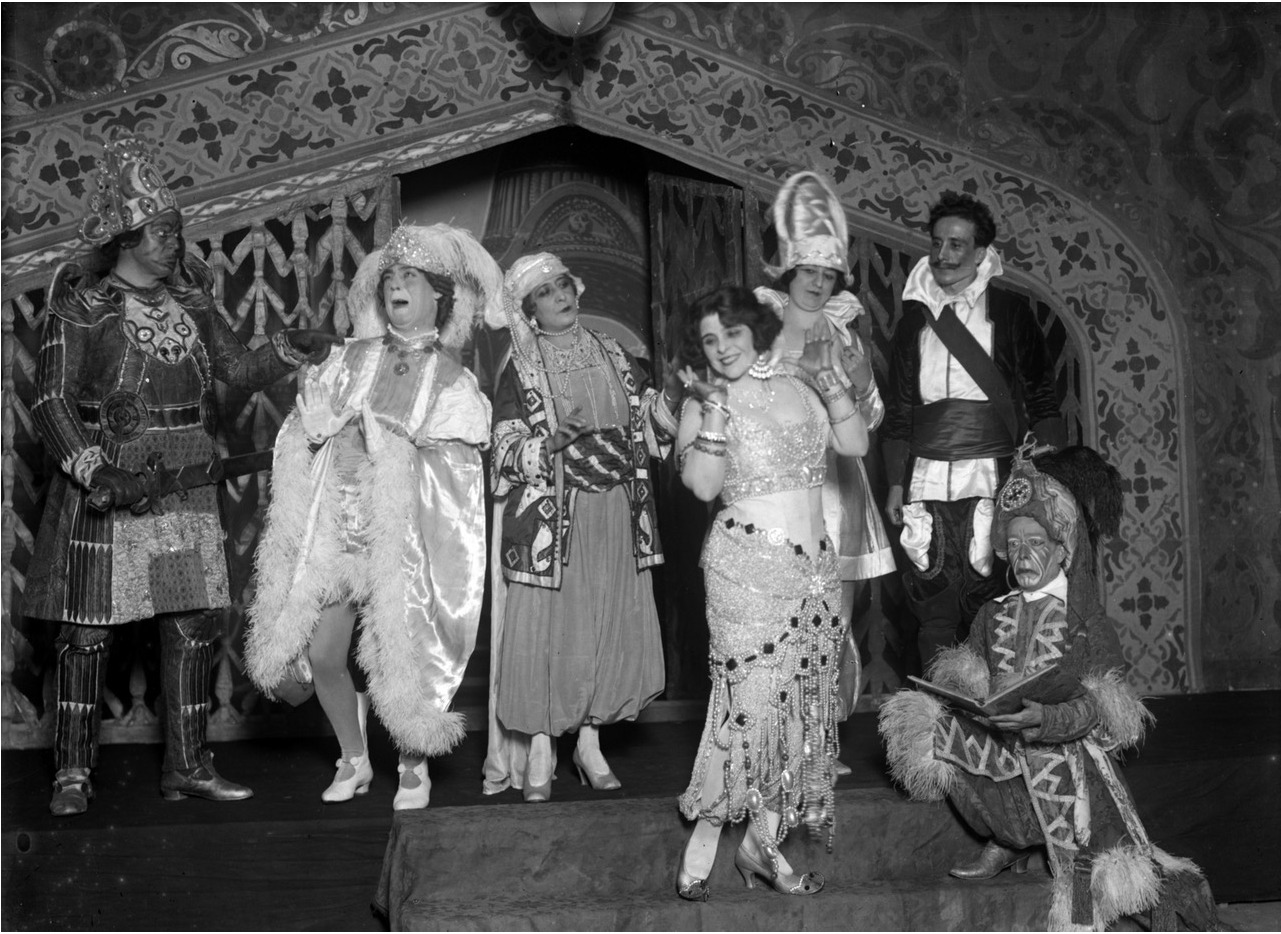

Scene from a “Benamor” production of the Esperanza Iris Company in Mexico City, 1924. (Photo: : Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexiko / Agencia Casasola)

In the popular musical theatre repertoire, we find other works which loudly echo Volker Klotz’s reflection on the ‘happy end’ to Madame Pompadour:

Like most operettas, Madame Pompadour makes its musico-dramatic protest against the historical and social status quo not in the finale, but midway between the beginning and end of stage events. It is only in the middle section that what is represented decisively questions the everyday assumptions of those present in the theatre [...] For the untamed powers of the operetta cannot be measured by the final solution, which only mechanically placates them.

The piece I’ve chosen should be understood as a paradigm case of these ‘happy ends’ which do not fool anyone. Premiered at Madrid’s Teatro de la Zarzuela in 1923 (a few months after the Berlin premiere of Leo Fall’s operetta), Benamor is one of the most characteristic zarzuelas of the Roaring Twenties; a work which, as a whole, can be considered one of the signal queer products of Spanish creativity at the time.

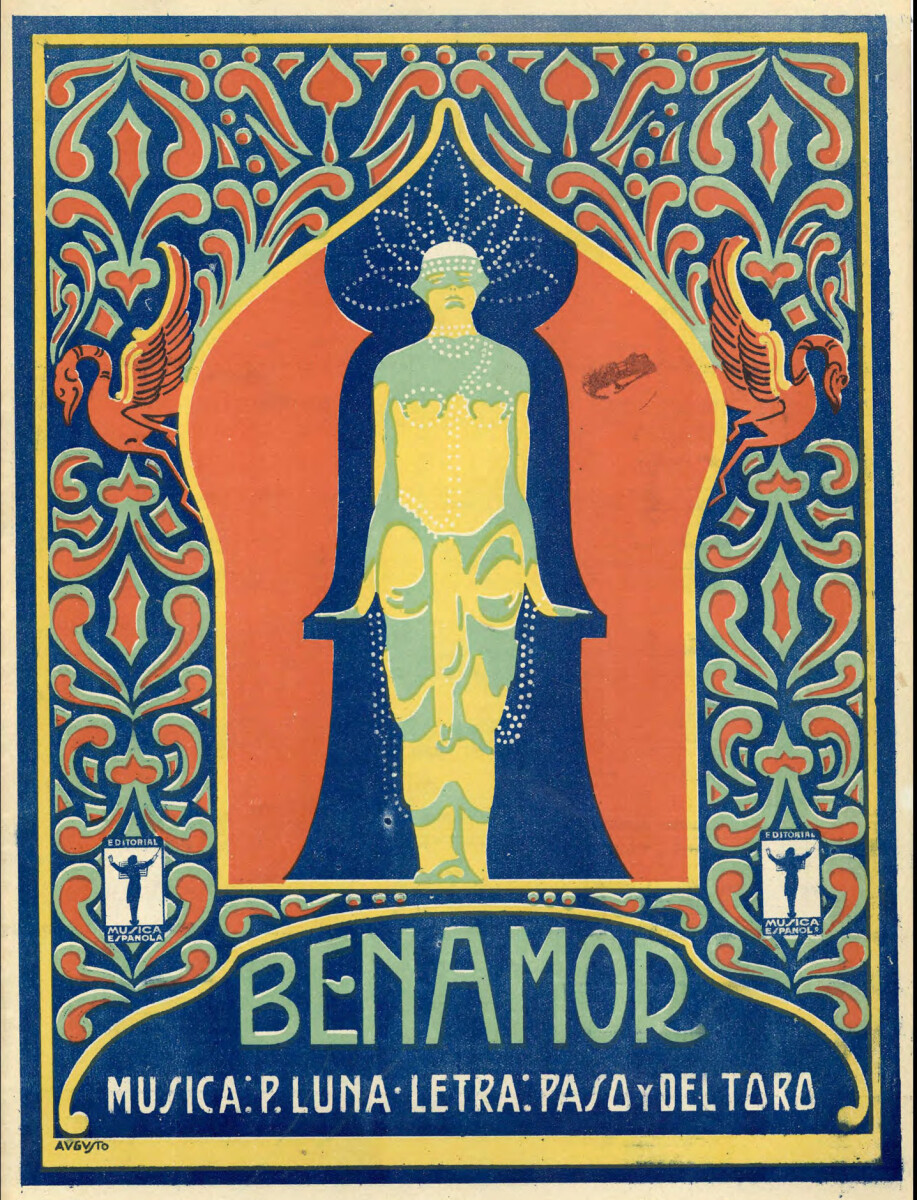

The title page of the “Benamor” piano score. (Photo: Editorial Musica Espana)

Until the denouement in the final scenes of the third act, Benamor’s librettists – Antonio Paso Cano and Ricardo González del Toro – display equivocal sexualities and more-than-diverse gender identities on the stage, in a setting that ultimately harks back to Offenbach’s L’Île de Tulipatan.

In the case of this operetta “inspired by a Persian legend” we find ourselves at the court of Darío, a young sultan who is said to be “too weak to be a man” and who shows no interest in his harem. As for his sister, Princess Benamor, it is whispered of her manners that anyone would “take her for a boy”. Needless to say, neither is aware of their true identity: Darío is female and Benamor is male (although ‘he’ is in fact a trouser role). This quid pro quo is the responsibility of none other than the Queen Mother, who thus avoided the application of a bloody law which required the beheading of the first-born if it was not a boy, and of the second-born if it was not a girl.

The diva Esperanza Iris in “Benamor” in Mexico, 1923. (Photo: Archivo Esperanza Iris, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura. Centro Nacional de Investigación, Documentación e Información Teatral Rodolfo Usigli, México)

Matters become more complicated in time, when suitors for the hand of Princess Benamor arrive at the court. In the wake of a fierce-looking butch warrior with a face full of scars, and a petit prince his reverse in every way (“blond, slender, delicate”, affectionately gay), Juan de León appears – a Spanish adventurer, the prototype of the Iberian macho man, as dashing as he is romantic. He claims to have come from fighting in the Flanders wars (this is the 16th century) and represents the interests of an unknown prince. Surprise! Juan de León quickly attracts the attention of Sultan Darío: “If I were my sister, I would choose this one”.

At this point in the first act comes the trio I’ve selected as an unforgettable moment, precisely because of its disruptive nature. The Sultan asks Juan de León to woo his sister with the words of love that would be used by the prince he claims to represent. The false princess – need I say it? – feels no attraction to the Spaniard, but becomes enthusiastic when she hears him talk of fighting. Darío, frightened by Benamor’s inappropriate reaction, decides to teach his sister how to respond to such gallantries. Juan de Leon, taken aback, at first refuses to play along. The Sultan is triggered: “You don’t dare?… Then I’ll do it”. At that moment, time stands still and Darío, accompanied by a violin and harp, expresses his passion:

Gallant knight you come to my side,

wrapped in mystery

and a joyful smile between your lips,

your adventurous life

I would like to know,

lord of illusion,

who are you, that awakens my hope?

The sincerity of the moment is beyond doubt. Pablo Luna’s inspiration is fragrant and sophisticated. So much so that our macho man becomes frightened as the game progresses (“I don’t know what strange feeling comes over me”) and chooses to address the Sultan as feminine when asked to do so. The musical intoxication emboldens Juan de León who, in the end, will have no problem declaring himself as he looks into the eyes of another – supposed – man:

Your lips are twin ribbons of fire

that I would like, princess, to kiss.

Let me come close to your lips,

for on your lips I would burn with love.

The whole string section underlines in unison the passionate melody which is finally free of orientalist pentatonics and melismas: that’s what real love is like in Spain. In the midst of so much homoeroticism, Benamor feels that he is left out: “They don’t remember that I’m here”.

This trio, despite its undeniable musical interest and theatrical power, was suppressed after the premiere. There may have been several reasons for the cut. The score itself is very long, and the number extends the presentation of a conflict that has already arisen. Moreover, almost immediately afterwards comes the first-act finale, into which is inserted Juan de León’s spectacular patriotic romanza (“¡País de sol!”), the hit number that ensured Benamor’s permanence in the repertoire. It is plausible that, at some point, the trio was felt to bring forward the baritone-star’s musical entry, and in that sense detract from the spectacular impact of the romanza or unnecessarily fatigue his voice.

A scene from the original 1923 production of “Benamor.” (Photo: Archive of SGAE / Teatro de la Zarzuela)

However, as a musicologist, spectator and fan, I prefer to speculate on less obvious reasons. Benamor’s score has fourteen musical numbers, all based on danceable rhythms and/or organised in strophic structures of undeniable lightness. Alongside the foxtrot, the shimmy, the Boston waltz and a surprising cameltrot full of syncopations, there are the usual military marches, buffo couplets and a lavish Fire Dance, all brought together by Luna’s inexhaustible inspiration and dazzling orchestration. The trio, though, seems to contradict the general, almost revue-like tone, endowing the moment – as I have tried to explain – with real humanity.

Perhaps that is why it might have been suppressed, because it implied that the same adventurer who would later glorify his nation and its beautiful women in his romanza was here declaring himself ‘for real’ on stage to another man [or seeming man]. Homophobic misgivings? Patriotic complexes a few months before General Miguel Primo de Rivera’s coup d’état? Be that as it may, Juan de León resists entering this ‘cabaret’ in three acts and is always very self-conscious, restrained and attired like one of those knights looking into the eyes of the beholder in Velázquez’s The Surrender of Breda.

Diego Velázquez’s “The Surrender of Breda”, 1625. (Photo: Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Only when he learns the humdrum truth, in the operetta’s last number, will he let himself be carried away in the triple-time rhythm of his duet with Darío. However, the memory of that trio makes him shudder, asking in the past tense: “Why, little princess, did you speak to me of love?” The routine waltz, slow and sticky as honey, re-establishes that “historical and social status quo” (in Klotz’s words), although many spectators in 1923 had to return home with that trio in which everything seemed possible resounding in their heads. Benamor himself, on discovering that he is a man, chooses to fall in love only with a slave, whom he warns in his third-act duet, “You will be my slave, I your master”. Before that, however, he has already wandered around the harem rubbing up against the odalisques.

Predictably, from 1939 onwards Benamor ran into problems with Franco’s censors, who considered its subject matter “fundamentally dangerous”. That same sense of danger may have led its creators to cut the trio during the Roaring Twenties. Fortunately, the music survived in the manuscript orchestral parts that we have preserved in Madrid’s SGAE Archive, where I have been working as a music editor since 2009. From them I was able to reconstruct the orchestral score with which Benamor has been recently revived, in the theatre where it was first performed a century ago.

Enrique Mejías García works for the archive of the Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE) in Madrid; he is also the author of a new Spanish language book on Jacques Offenbach (read more about it here).

The 2025 edition of “Glitter and be Gay: Releaded”. (Photo: Männerschwarm / Salzgeber)