Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

16 January, 2019

Last week the international operetta research world gathered in Leeds for a conference which was – nothing short of remarkable! Most of all because novel topics where presented that had previously been mostly absent from English language discourses: e.g. about operettas written in Socialist and Communist countries that celebrate the new utopian post-revolution life and the blessings of working class aristocracy, or, on the other hand, the purely capitalist economics that connected the South American operetta market with Italy and how Italian impresarios fed the Latin market in the early 20th century with hit shows from Vienna, London, Paris and Italy, creating a unique mix not found elsewhere.

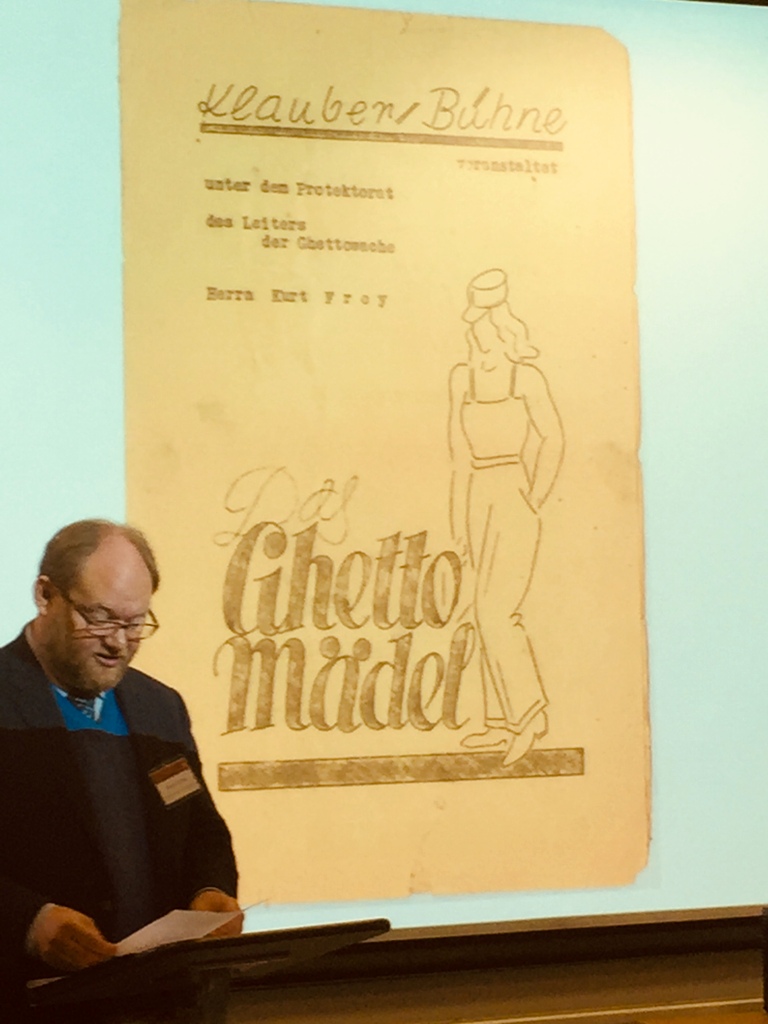

James A. Grymes from the University of North Carolina presenting “Das Ghetto Mädel” which was performed in Theresienstadt. (Photo: Private)

The researcher who presented the latter topic was Matteo Paoletti from the University of Genoa, looking at operetta as a checks-and-balances market and via financial figures, something overdue with regard to Continental European operetta after decades of merely discussing melodic beauty and plot innovations (or the lack thereof). If you read the correspondence between Emmerich Kalman and Hubert Marischka at Theater an der Wien, for example, or Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s correspondence with publishers about Johann Strauss and Leo Fall, you realize quickly that it’s all about money, royalties, contracts, casting ideas, extra fees etc. and very little about so called ‘art,’ let alone music.

Intellectual Rhapsodizing

Accepting and analyzing operettas as financial properties – and overcoming the standard Volker Klotz school of intellectual rhapsodizing (‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’) – seems an obvious next step. Broadway and Hollywood historians have demonstrated the benefits of integrating such discussions into the wider picture long ago.

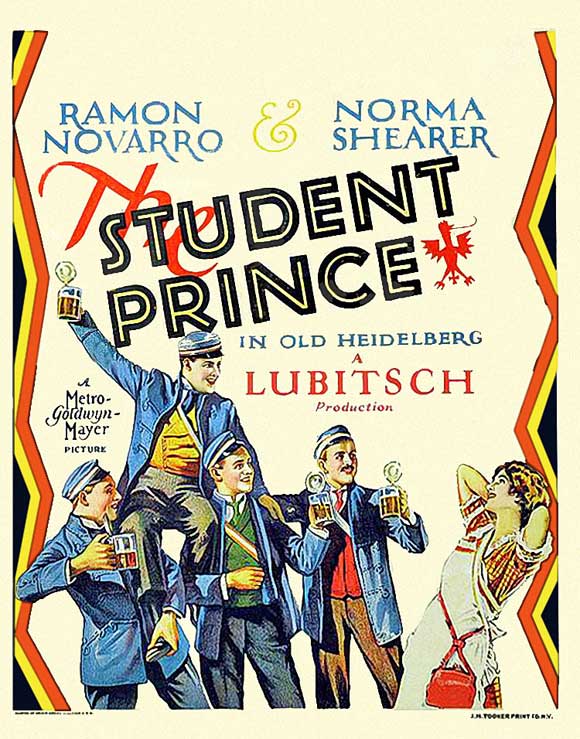

Poster for the first film version of “The Student Prince”, directed by Ernst Lubitsch in 1927.

John Graziano from City University New York showed how such transatlantic transfers worked on Broadway. He looked at original German language operettas and their US adaptations, explaining when the Viennese operetta boom in NYC peaked and when/why it subsided. Most simply because American authors such as Romberg and Friml could write operettas themselves and directly for Broadway. Their Rose-Marie and Student Prince were smash hits, replacing the earlier Merry Widow and Chocolate Soldier craze.

Vojtěc Frank (l.) and Magdolna Jákfalvi discussing “Socialist Realism and Totalitariansim” in operettas from Hungary and Czechoslovakia. (Photo: Private)

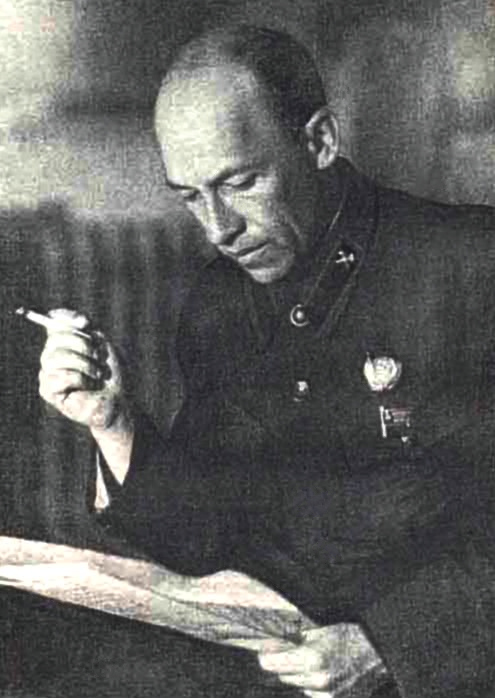

The analysis of operettas in Socialist and Communist countries, e.g. Czechoslovakia, Hungary and former East Germany (DDR/GDR) showed that the related repertoire is not just of local interest anymore but can give fascinating insights into the political mechanisms of show business, and its ideological abuse. Particularly fascinating was Vojtěc Frank’s talk on the Czech situation and how Soviet operettas by Isaak Dunayevsky (1900-1955) were elevated to role model status. By demonstrating how these Russian operettas were performed in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s vs. 80s, Mr. Frank chronicled the changing relationship between both countries. His film example with scenes from the 1955 White Acacia was stunning, and made the demise of Soviet operetta abundantly clear – when you saw the early 70s version.

Soviet composer Isaak Dunayevsky in uniform. (Photo: Wikipedia)

For me, it was also refreshing to meet new researchers busy with GDR operettas, because for the longest time it seemed that this was a single-scholar endeavor. It’s not anymore! There is Katrin Stöck from the University of Halle who seems to be teaming up with the Leipzig University forces to expand this field of research. There is a book coming up about this as well, edited by Wolfgang Jansen. This book will be in English to reach a larger audience.

Various famous operettas from Eastern Germany, as presented on an LP cover in the GDR.

Other talks were by Magdolna Jákfalvi from the Budapest University of Theatre and Film Art (“Socialist-Realist Operetta”) and Daniel Molnár (“Operetta Parodies on Variety Stages in Budapest Between 1931-1968”).

Magdolna Jákfalvi from the Budapest University of Theatre and Film Art and Kevin Clarke from the Operetta Research Center Amsterdam. (Photo: Private)

Gyöngyi Heltai from the University of Alberta in Canada spoke about “Transnational influences in the early period of the Budapest Operetta Theatre, 1922-26.”

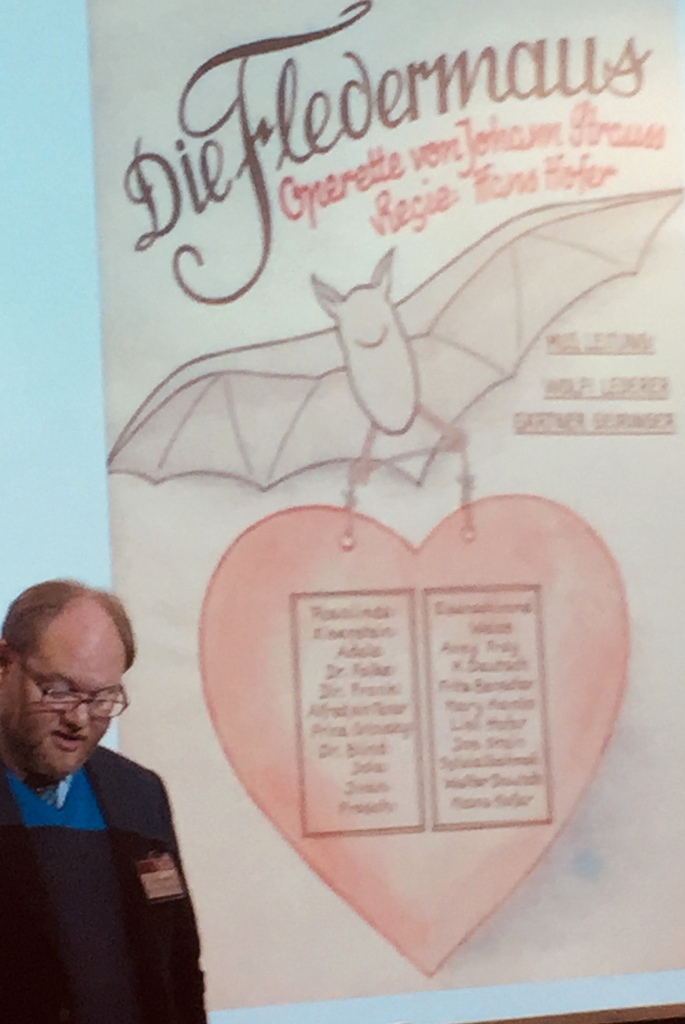

James A. Grymes discussing a “Fledermaus” production in Theresienstadt. (Photo: Private)

Another topic discussed at the conference, which I had not noticed much in English language publications before, was the Nazi influence on operetta history, and how operettas were performed in concentration camps. James A. Grymes from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte gave an amazing talk on “Adaptations of Operetta in the Nazi Camp-Ghetto of Theresienstadt.”

Gender Ambiguity and the Repression of Sexual Identity

Gender and sexuality were also a big issue in various talks, e.g. in the context of The Geisha (William A. Everett from the University of Missouri) or The Shop Girl , or in relation the breeches roles and early French operettas.

Sonja Jünschke from the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt a. M. speaking on “Places of Commerce in Late Victorian Popular Musical Theatre.” (Photo: Private)

Having Beatrice Beer at the conference for an evening recital in the Clothworkers’ Centenary Concert Hall, with music of her father Joseph Beer, was an experience, even if Miss Beer with her heavy-duty Verdi soprano is not the best-suited interpreter of such light music. After all, Beer’s Polnische Hochzeit (1937) was supposed to be sung by Marta Eggerth, not Maria Callas in the later stages of her career.

Beatrice Beer and her pianist Derek Scott during the recital at Clothworkers’ Centenary Concert Hall. (Photo: Private)

Also, compared with other composer’s children, Beatrice Beer seemed somewhat erratic in her narrative, but also endearing and certainly memorable. She roused interest in Polnische Hochzeit which is currently playing at the Opernhaus Graz.

Part of the gender focus were also John Rigby talking about “Der Zarewitsch: Gender Ambiguity and the Repression of Sexual Identity,” and Matthew Head speaking on “The American Lady Composer as Character Type in Operetta and Musicals in the 1930s” – the famous example being Daisy Darlington in Ball im Savoy (1932).

On a related note, Pierre Degott (Université de Lorraine) spoke about “Sexual Predation and Textual Correction” from Bettelstudent and Zigeunerbaron to Veronique and other shows. This opened up the field of sexuality and gender even wider, and I personally would have loved to discuss all of this at greater length, especially comparing the male protagonist examples with female characters in operetta who are sexual predators, starting with the Grand Duchess of Gerolstein.

The conference organizer Derek Scott and his team (including Anastasia Belina from the Royal College of Music in London) went out of their way to make the conference a pleasant and lively experience. Giving ample time at lunch, coffee and dinner for researchers to discuss in smaller groups and exchange thoughts, material, and email addresses.

The presentation “Operetta as Safe Space” at Clothworkers’ Centenary Concert Hall. (Photo: Private)

Allowing the Operetta Research Center Amsterdam to present a key note lecture at the Clothworkers’ Centenary Concert Hall, on “Operetta as Safe Space,” was a big bonus, especially since I was the one chosen to deliver it. Needless to say, that was a great honor, and the discussion that followed about Lucille Tostée (Offenbach’s first Gerolstein in the United States) and others proved that there already is a lot of research on individual aspects of that key note talk.

Hungarian singer Hanna Honthy as Offenbach’s Grand Duchess of Gerolstein in 1950, Budapest. (Photo: Hungarian Theatre Institute / operett.network.hu)

With a little bit of luck there will be a book with all the papers. (Fingers crossed.) And please pardon me for not listing all speakers here: the other talks were equally thrilling!

Song, Stage and Screen

And since Leeds and its vibrant city center are always worth a visit: there is another conference coming up in June 2019, as part of the Song, Stage and Screen series. The upcoming edition is dedicated to (Re-)Inventions: Adaptations and New Directions in Musicals on and between Stage and Screen.

One of the many historic arcades in Leeds city center. (Photo: Private)

From all of us at the Operetta Research Center Amsterdam I can only say thank you to Derek Scott for having moved operetta research noticeably forward for English language scholarship and for bringing it together with trends from other long-ignored countries. Derek Scott himself has edited the new Cambridge University Press book on operetta, due in September 2019.

Stay tuned!

For more information on the conference, click here. An interview with Derek Scott about the conference can be found here.