Michael H. Hardern

Operetta Research Center

16 November, 2014

It is an inventive new approach to an old question: how do we deal with the ideological baggage of operettas written in Nazi times? Can we play these often still popular shows if their subtext transports ideals (women’s rights, race, war, discrimination) that we would normally not support? Are we allowed to pretend these ideals are not there? Or can we “save” some of the shows from their fascist past by reinterpreting them?

The first film version of “Maske in Blau,” 1941/42, starring Clara Tabody and Hans Moser.

For decades, there were two ways of dealing with this situation: either directors did not play particular shows at all, because they were “tainted,” or they pretended they did not know anything about the authors’ (or the shows’) political background. For example: the works of Nazi Germany’s top operetta man, Heinz Hentschke (1895-1970), were not put on stage in Eastern Germany until to 1980s. While theaters and radio stations in the West performed his Maske in Blau as something that is just fluffy operetta nonsense with beautiful tunes attached, never mentioning Hentschke’s political background.

Recently, there has appeared a third way, first successfully applied by the Komische Oper Berlin, and now followed by the Theater der Altmark in Stendal.

In Berlin, after a series of revived jazz operettas of the pre-1933 era, Nico Dostal’s Clivia was presented. It is a show from December 1933 that cleverly incorporates the new operetta ideals of the new political regime – in terms of content and cleaned-up sound. The Komische Oper promoted the show as a “jazz operetta,” putting it in a line with their earlier productions, thus avoiding a political discussion.

To facilitate this, the Dostal score was newly arranged, making it sound more “degenerate” than it was ever intended to sound.

Also, an earlier “Schlager” by Dostal was added, from his pre-1933 career and very “American” in style. This, too, gives the new version a Twenties flair the original show does not habe. With amazing cross-dressed casting of the title role, all other Nazi associations were blown away or ironically turned upside down, and the Komische Oper scored a major triumph. Only on one occasion did the company stage a pre-performance discussion about “Is Clivia a Nazi Operetta?,” demonstrating that the problem did not go unnoticed entirely. It was just not pushed into the spot light, as before with the Paul Abraham revival of Ball im Savoy, where talk of Nazi politics was central. As it surely will be, again, with the Oscar Straus revivals later this season.

The Theater der Altmark in Stendal put on Werner Richard Heymann’s Drei von der Tankstelle last season, in a snappy and stylish production conducted by Jakob Brenner. They followed this work from the canon of “degenerate” jazz titles with Fred Raymond’s Maske in Blau, which originally premiered at the Metropoltheater in 1937 and was co-authored by the afore mentioned Heinz Hentschke. Again, the typically lush late 1930s score was newly arranged to make it sound more bouncy in a Roaring Twenties kind of way (even though the production actually sets the story in the 1960s). And: two Schlager from Raymond’s earlier career were inserted, written with Jewish authors and decidely Dada (and cheeky) in style, were inserted, balancing the later trivial dance numbers supervised by Hentschke. One is “Ich reiß mir eine Wimper aus,” which was turned into a kind of gay anthem back in the Twenties and which certainly is everything the Nazis would have labelled “degenerate.”

Stage director Sarah Kohrs erased all obvious references in the dialogue to Nazi times, and played – again, like the Komische Oper – with the gay element.

In this case not via cross-dressing, but by turning one of the buffos (played by Michael Magel) into a camp fashion designer called Franz Kilian, who ends up in the arms of another buffo (Frank Siebers as major domo Gonzala). It is him, of course, who sings the song of the “Wimper” (an eye-lash pulled out to stab the enemy.)

Michael Magel camping it up as Kilian, in “Maske in Blau” in Stendal.

Stendal’s intendant, Alexander Netschajew, did not want to bow out of any critical questions, however. So he scheduled a pre-premiere discussion about the Nazi past of Fred Raymond, Heinz Hentschke, Maske in Blau etc. with the head dramaturg, Aud Merkel, a representative of publishing house Bloch Erben, Boris Priebe, and a member of the Operetta Research Center, Kevin Clarke.

The surprisingly large audience turn-out demonstrated that there is a lot of interest in the topic.

It also demonstrated that after an in-depth discussion of musical and theater history you can go and simply enjoy a fresh and attractively cast production of one of the most famous operettas from Nazi times. The two stand-out performers were, without doubt, Ricardo Frenzel Baudisch as Armando Cellini and Andreas Müller as Josef Fraunhofer. Both are ready for big careers.

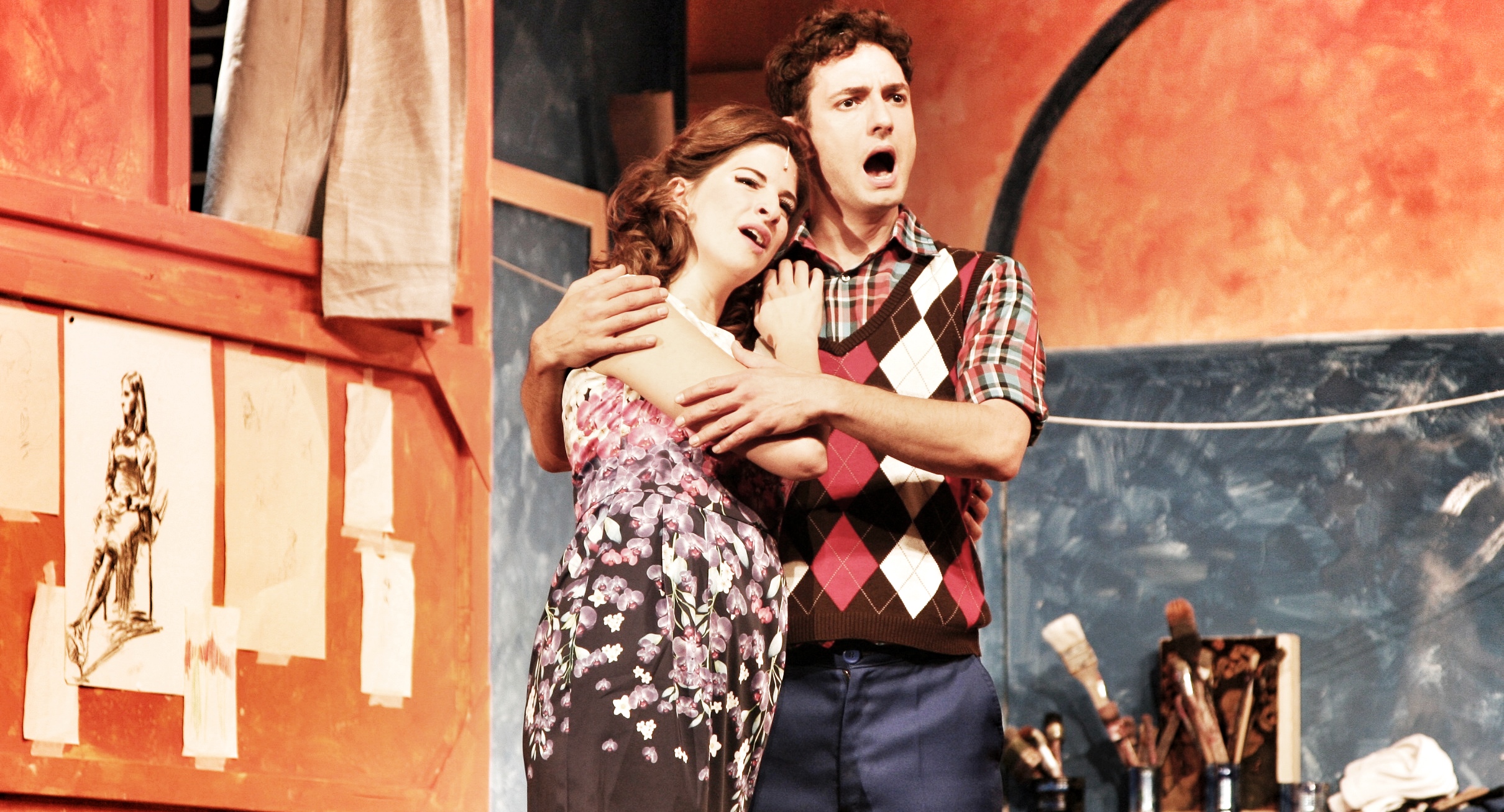

Ricardo Frenzel Baudisch as Armando Cellini and Larissa Neudert as his love-interest Evelyne Valera.

It will be interesting to see how other theaters will present more titles from the 1933/45 repertoire in the future. The Komische Oper and the Theater der Altmark have demonstrated that the right casting, ironic staging and new orchestrations can give some of these problematic shows a new life that they absolutely deserve. Because they represent one of the most fascinating and interesting aspects of operetta history that deserves discussion and attention, instead of silence and ignorance. Which has been the case for too many decades.

Pre-performance discussion in Stendal, with Aud Merkel (middle), Boris Priebe (right) and ORCA’S Kevin Clarke.