Michael Miller

Operetta Foundation

9 November, 2016

It is seemingly inevitable that a conversation among Broadway aficionados about composer Sigmund Romberg (1887-1951) eventually turns to the question: “He wrote all those masterpieces … how bad can the other works be?” Indeed, it is virtually impossible that the creator of the eternally engaging melodies for Maytime, The Student Prince, The Desert Song, and The New Moon would not have mustered up much of that same creative genius for the remaining 60 shows to which he contributed songs.

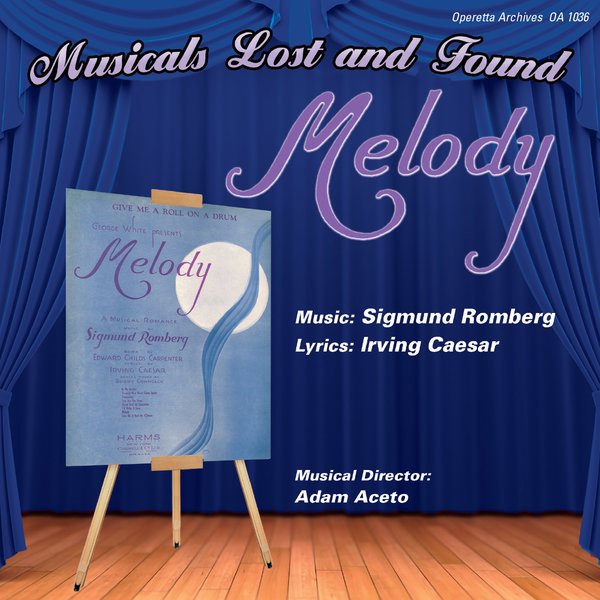

CD cover for the new cast album of Romberg’s “Melody.”

Embarrassingly for our perceived musical theater legacy, even the aficionados would be hard-pressed to name more than a handful of tunes from these other shows: “Auf Wiedersehn” from The Blue Paradise (1915), “Silver Moon” and “Your Land and My Land” from My Maryland (1927), “The Fireman’s Bride” and “Close as Pages in a Book” from Up in Central Park (1945), “Up in an Elevated Railway” from The Girl in Pink Tights (1954), perhaps a few others, as well of course as his adaptations of Franz Schubert melodies for Blossom Time (1921). Yet virtually nothing is remembered from his later shows such as Cherry Blossoms (1927), East Wind (1931), Sunny River (1941), or My Romance (1948), or from his early revues and musical comedies: A World of Pleasure (1915), The Girl from Brazil (1916), My Lady’s Glove (1917), The Melting of Molly (1918), or Annie Dear (1924), to name just a few. During the 1930s, Romberg wrote five Broadway musicals: Nina Rosa, East Wind, Melody, May Wine, and Forbidden Melody, whose combined performance run was less than that achieved solely by Blossom Time, The Student Prince, or The New Moon … or for that matter Up in Central Park, his antepenultimate Broadway show, which very successfully followed the string of six all-but-forgotten shows that succeeded The New Moon.

The 1930s were a miserable time for operetta and old-fashioned romantic musicals on Broadway. The forms were deemed outdated by the critics and by audiences that were newly attuned to sound films, the excesses and modernity of the Roaring Twenties, and a “new” Broadway that was ruled by the likes of George Gershwin, Cole Porter, and Rodgers and Hart.

Romberg was in no better position during the decade than Rudolf Friml, whose two shows (Luana and Music Hath Charms) were both unmitigated failures and closed out his stage career, or Oscar Hammerstein II, who contributed lyrics to six shows, four with runs under 70 performances, and was thought totally washed up. So … do we blame Romberg’s failures during that period on a long-term collapse in creativity, or on the mismatch of his creativity and the rapidly evolving demands of the public?

Time and history work quickly in passing judgment—most shows have only one chance.

If the opening Broadway run is a failure, the work is most often relegated to permanent oblivion. One of the goals in presenting this musically-complete recording of Romberg’s 1933 musical romance Melody, which opened on February 14, 1933 at the Casino Theatre and ran for only 79 performances, is to at least give the listening public an opportunity to form its own opinion. Hardly a note from the score has ever been recorded. Aside from Romberg’s music, Melody features the lyrics of Irving Caesar, who, most famously, did the honors for George Gershwin’s song “Swanee” and Vincent Youmans’ “Tea for Two” and “I Want to Be Happy” from No, No, Nanette.

Sheet music cover for Romberg’s “Melody.”

The book was by established playwright Edward Childs Carpenter, and stage direction was by famed Scandals impresario George White, who also produced the show. Legendary scenic designer Joseph Urban did the sets and musical factotum Al Goodman conducted the pit orchestra. It is a fascinating show, more sophisticated in its musical stylings and use of leitmotifs than presumably anything Romberg had done before. It harkens back to the operetta days of the 20s, but pays tribute to the inescapable musical comedy paradigms of the 30s. And … what would a Romberg show be without an irresistibly rousing chorus number (à la “Stouthearted Men” or “Drink, Drink, Drink”). The song in this case (“Give Me a Roll on a Drum”) — most certainly the take-away tune from the show—is introduced by the character of Paula as she entertains the guests at a Parisian café. No worry … the guests eventually join in.

The complex plot, in its multi-generational structure, is highly reminiscent of that of Maytime. Two young lovers, because of family intervention, cannot get together. In the earlier show, it is their grandchildren who meet by chance decades later and perpetuate the love of their grandparents. In Melody, it is her granddaughter who meets not his grandson, but a relation of a devoted family friend who has long since lost contact with the original couple and their descendants. In this recording, we have not included the dialogue, but have included (via the two pianos) all the musical underscoring that accompanies the dialogue between songs. To provide continuity so that the listener can keep up with the developing action, the CD booklet includes a quite detailed synopsis and complete track references.

The cast includes Nathan Brian as Pierre, Vicomet de Laurier and Natalie Ballenger as Andrée de Nemours. Also part of the team is Stephen Faulk as Tristan Robillard, “a composer”. At the piano: Adam Aceto and Brian O’Halloran.

Operetta crusader Stephen Faulk.

To order the doube CD directly from the Operetta Archives, click here.