Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

15 June, 2014

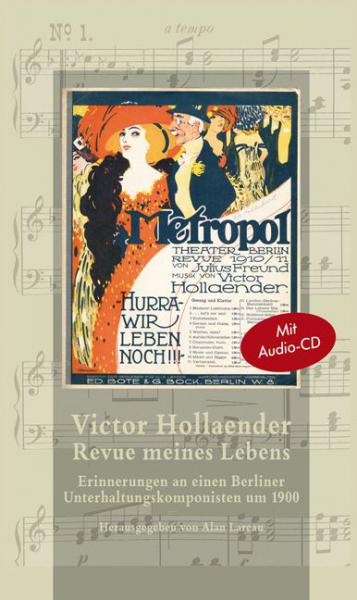

Alan Lareau, Professor of German at the University of Oshkosh and a scholar specialized in the cabaret culture of the Weimar Republic, has just published a wonderful little book on operetta composer Victor Hollaender (1866-1940) entitled Revue meines Lebens: Erinnerungen an einen Berliner Unterhaltungskomponisten um 1900 (272 pp, Hardcover). It examines the cabaret-, operetta- and revue scene in Berlin, London and the USA in the early 20th century. We caught up with Dr. Lareau on a sunny week-end in Oshkosh and quizzed him about his book, and asked him about Victor Hollaender’s famous songs and shows, as well as about his reputation in the Anglo-American world of musical comedy.

Alan Lareau, one of the wolrd’s most famous Hollaender family researchers.

You have just edited a very attractive little book on operetta and revue composer Victor Holländer, father of the überfamous Friedrich Holländer and creator of the Metropol-Theater “Jahresrevuen” which starred Fritzi Massary, among others. What fascinated you about Victor Holländer to devote time and energy into writing and publishing such a book in German?

I first encountered Victor Hollaender when I began collecting German sheet music and was fascinated by the elegant and clever cover illustrations, which conjured up a stylish time long gone. Later, when I began to research Friedrich Hollaender’s work more intensively, it became clear that his father, whose work he described most lovingly, was the inspiration and model for the son’s talent. During that research, my friend Karsten Schilling of Berlin stumbled upon Victor Hollaender’s unknown memoirs in a Berlin newspaper and copied the full text and gave it to me. It was a story that deserved to be preserved. Those memoirs are the heart of the new volume, alongside poems and articles by and about Victor Hollaender. The collection is meant to be a memorial to a figure who was beloved and influential in his day but has since been all but forgotten.

By the way, both Victor and Friedrich always spelled their names “Hollaender,” even though they were often misspelled with an umlaut, even in printed editions of their own works.

Considering how popular many of Hollaender’s pre-WW1 songs were, Victor is almost grotesquely underrepresented in today’s general memory, certainly compared to the likes of Paul Lincke and Walter Kollo. Why do you think that is so?

Simply put, unlike Kollo and Lincke, he was Jewish. His works were banned and discarded in the Third Reich, archives and publishers were destroyed in the war, and his work was for the most part lost. His own papers were lost in the wake of escape from Germany, and he died forgotten in exile. After World War II, nobody worked to revive his music and his memory—there was no Lotte Lenya to champion his work as in the case of Kurt Weill, who had also died in exile and was in danger of slipping into obscurity in Europe. But the music of 1900 also didn’t speak to post-war sensibilities, for it didn’t have the youthful transgressiveness of jazz and pop, and then of course rock and roll. The lyrics were so topical that they were only museum artifacts, though the “Schaukellied” and “Kirschen in Nachbars Garten” lived on as nostalgia pieces. That at least these two songs have remained “classics” is itself an accomplishment.

The cover of Alan Lareau’s new Hollaender book.

Victor Hollaender also fell into obscurity because, as he himself admitted, the stage scripts for the many operettas and comedies he set were often of poor quality. His early works, for which he wrote his own words, were amateur theatricals and comic musical scenes for school and household use—that is a culture that has died out. It could well be, too, that like his son, Victor Hollaender was more a man of the small form, the song, rather than the full-length work, which he perhaps could not sustain.

You write, in your book, that the “Kaiserreich”, i.e. the monarchy before 1918, is a “poor cousin” of cultural history. “Even though that’s where the roots of Modernity are to be found, this supposedly stuffy, authority loving era has always stood in the shadow of the much more popular Golden Twenties and the fatal attraction the Nazi era exudes.” 2014 is the centenary of the beginning of World War 1. Do you see a rekindled interest in the times before 1914 and the entertainment industry that Victor Hollaender was an important part of? What characterizes that entertainment industry, compared with later eras?

The era has indeed received new attention, but in music and popular entertainment, we’re still fascinated by and working through the story of the twenties and thirties. The impudence and explorations of jazz and media culture, the struggles of Germany’s first democracy, and the resistance to authority and the rise of Nazism are the more urgent stories to recover.

Composer Victor Hollaender.

The discrete elegance and stylishness of the Metropol revues are far removed from our experiences and hard to consume as entertainment. All the topical allusions, the carefully packaged double entendres and camouflaged attacks on morality and authority are too indirect for today’s listeners to appreciate. Today’s satire is usually in your face and crass, provoking and taunting rather than flirting and teasing. Thankfully, we don’t face the kind of official censorship Victor Hollaender and his colleagues struggled with. But perhaps we have lost some of the sensitivity and cleverness they needed to succeed.

Victor Hollaender might have been a representative of “stuffy” pre-war operetta and revue in Berlin, but he was an internationally active composer who worked, more than once, in the USA and in England. Is it typical for Berlin operetta composers of that time to be so internationally active—and isn’t that something we associate more easily with the transatlantic composers of the Twenties?

There was a vital German-American theater scene in the United States, especially in Milwaukee, where Hollaender was the first musical director of the Pabst Theater, which still stands today as a cultural hub of the city. These groups performed Victor Hollaender’s works around the country. In New York, of course, international operetta hits were performed in the original languages. Talent scouts went to Europe to hire artists—actors, singers, musicians and writers–to tour America or to write new works for their theaters. That’s how Victor came to visit America twice: He was hired to work in Milwaukee in 1890 (on the ship with him, going on tour across America, were Richard Tauber’s father and a Berlin troupe of Liliputians) and in New York and Chicago in 1912.

All this exchange predates those businessmen who famously lured film industry talent to Hollywood in the twenties.

Victor Hollaender had three extensive stays in the USA. Is there any interest in his life and oeuvre in the United States, by musical theater historians? Is the German language theater scene of the late 19th and early 20th century part of the study programs in the US? And will there be an English language version of your book?

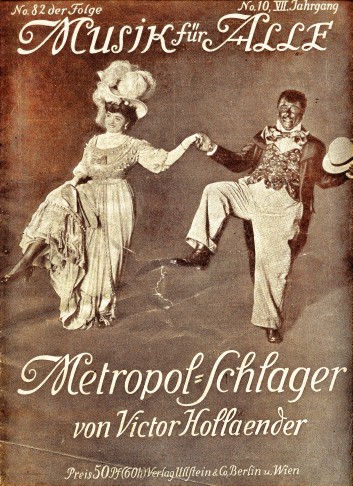

The look of Berlin revues at the Metropol Theater, pre 1914.

Victor Hollaender is barely a footnote to American theatrical history, and his 1912-13 career here was not successful. After opening in Chicago, A Modern Eve (an adaptation of Jean Gilbert’s operetta) toured the country, but by the time it got to Broadway, Hollaender’s new tunes had disappeared, and The Charity Girl was a flop. So he never made a lasting mark in America’s English-language theater scene. Only in the last years has the German-American theater enjoyed some first scholarly interest, as in John Kogel’s study of Music in German Immmigrant Theater of 2009, which focuses on New York City. There is a lot of research yet to be done in this field.

No English-language version of the book is planned; it’s really a story of and for Berlin, I think.

You claim that Victor Hollaender’s music gets its “urgency” from the “provocative mix of modernity and nostalgia.” Can you explain what that means, and how it translates into music in his case? Which songs would serve as a good example here?

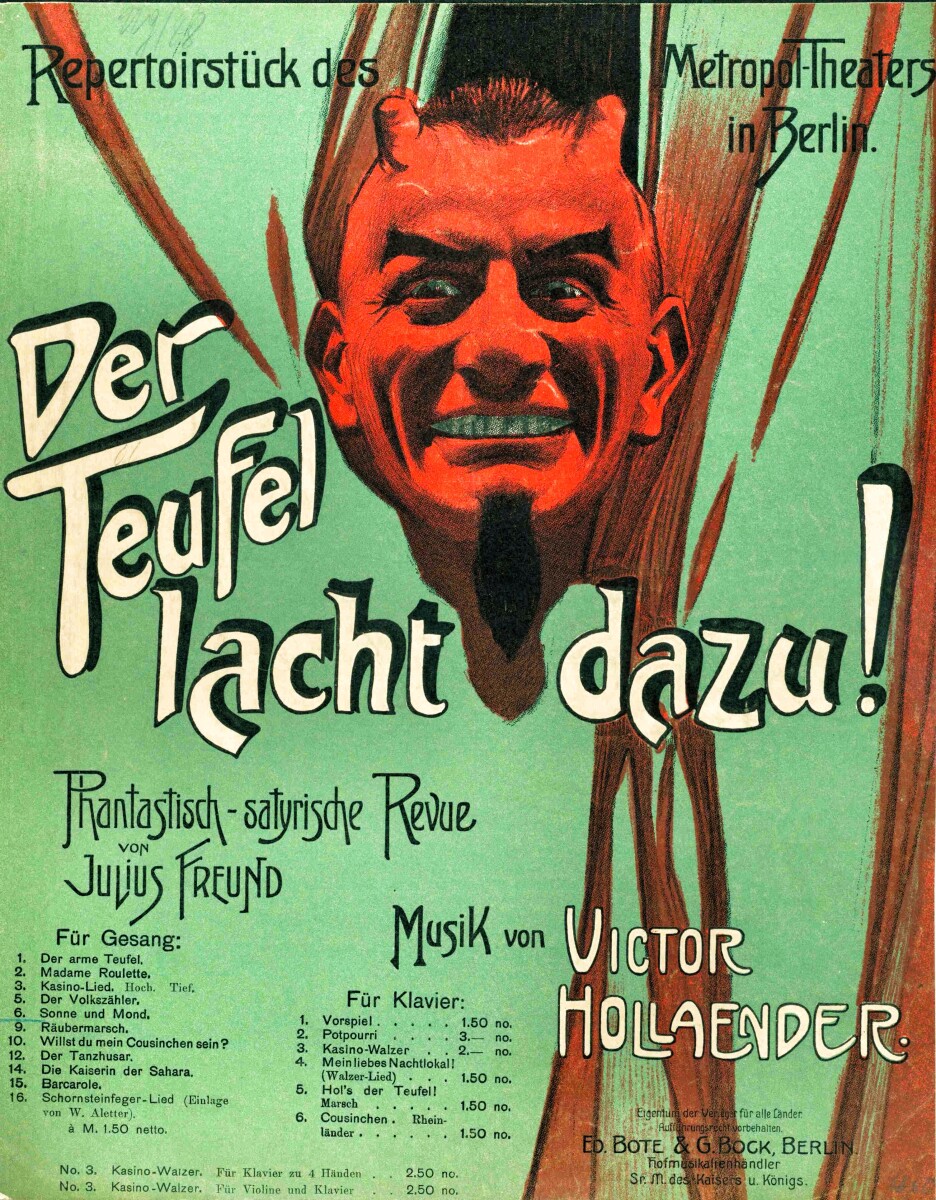

While Julius Freund’s lyrics express pride in Berlin’s rise and celebrate progress, songs like “Du mein altes Berlin” and “Der letzte Taler” also long for bygone, simpler days—and Victor Hollaender’s memoirs devote much time to recalling the joys and adventures of his childhood. I’m struck by the recurrent theme of the passing of time, the advance of old age, and the inevitability of death and decay in these songs. It’s a double-edged characteristic of simultaneous laughter and tears that his son Friedrich Hollaender would come to exemplify with his surprising mixture of “decadence” and sentiment, though even he admitted that those old songs had a level of sophistication and cleverness to which he could not himself aspire. “Die Jahreszeiten der Liebe” relates the life of a man from the spring of his first cigarette and his first kiss through his life of pleasure and love, up to the winter where that love is but a cherished memory; in the popular “Kasino-Lied,” the dandy revels in gambling, booze and women until the angels bear him away to heaven, where he begs to return to the nightclub that always gave him such joy. The songs remind us to enjoy life’s pleasures while we can, for they vanish all too soon. And like the songs of cabaret in all ages, they seize on the changing morals of the day and mock the passing of the old while looking ahead to the new with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Sheet music cover for “Der Teufel lacht dazu”.

While the Kollos and Paul Lincke have fared well in and after Nazi times, composers such as Jean Gilbert – one of the most important colleagues and competitors of Hollaender Sen. – are totally forgotten today, though both had famous sons who are omnipresent still. Why did the son of Victor Hollaender not use his immense influence and wealth to promote his father’s work after 1945?

When Friedrich returned to Germany in 1955, he was concerned with reviving his own career and fortunes. By no means did Friedrich have “immense influence or wealth”—he always lived over his means and struggled desperately for recognition and work, and on his return to Germany, the sixty-old man found himself a forgotten figure of yesteryear. Friedrich was, alas, not a good businessman or promoter. In the sixties, he transferred the copyrights to his father’s work (presumably sold them, or exchanged them in discharge of his debts) to a Hamburg music publisher who never did anything to promote the music. Friedrich loved his father dearly, but he had no sense of duty to preserve and foster his father’s works after the war.

Why do artists such as Dagmar Manzel, who recently released a whole disc of Friedrich Hollaender music, not touch the songs of Victor?

Nobody knows the name or music of Victor Hollaender, and the work is hard to find nowadays. The sensibility is also very different; one must concentrate carefully on the long-spun lyrics to appreciate their stories and humor, and gallant tales of casinos, champagne and flirtations are so outdated compared to the modern themes of Weimar from jazzbands to drugs, sexual experimentation, and mass media—though by now, they may be distant enough to have some romantic charm once more. I wonder if anyone could even sing these numbers today.

It would take a kind of taste and refinement and a subtle wit that are probably a lost art.

As you rightly point out, the “esthetic of collage” used by Hollaender Sen. in the famous Metropol-Theater revues is very modern, from today’s point of view. Do you see a chance to re-evaluate Hollaender’s shows from a post-post-modern perspective?

It would be difficult to revive the revues historically because the topical allusions, taken from the newspapers and gossip columns of the day, are obscure or entirely lost. Nobody would understand the songs and skits; you’d have to issue a program booklet full of historical footnotes explaining songs like “Willi und Cilli” satirizing the Kronprinz, or “Das Kohlenmädel” about a crisis in the coal industry, or “Willst du mein Cousinchen sein?” spoofing a colonial sex scandal of the day. The shows would have to be completely rewritten to make them comprehensible. Today’s cabaret troupes can do this with contemporary themes, but with literary and musical styles more accessible to their audience. After all, the humor of these revues was that they picked up on the trends and styles of the day—contemporary cabaret uses the same technique, but the gulf between 2014 and 1910 is probably too wide to blend the two effectively.

A typical scene from a Hollaender revue in pre-WW1 Berlin.

He wrote many operettas, which you list in your catalogue of works at the end of the book. Are the manuscripts available for performances if someone would want to put on Striese in Kamerun (1887), The Dwarf’s Wedding (1891), Der Bey von Marocco (1894), Der Jockeyklub (1909), A Modern Eve (1912) or Der Schwan von Siam (1921)?

Sad to say, almost all of this work is lost. I have found a few scripts and many individual songs, as well as the occasional piano score, but only a couple of sets of orchestral parts for operettas. (I think that at least Der Regimentspapa and Die Schöne vom Strande survive.) Nobody has been interested in performing or preserving these works, least of all the publishers—there is no money to be earned here.

Sheet music cover for the Hollaender “Schaukel Lied”.

These are often very exotic titles. Is the exotism reflected in the music?

I’m afraid I can’t address this because I don’t know the music to most of these pieces. This project was devoted to reconstructing and preserving Hollaender’s life story and catalogue; actually reassessing the music itself will be the next task for someone better equipped to do that.

Do you have a personal favorite show you’d like to see, or a favorite song you would especially like to resurrect?

I would love to see König Rhampsinit performed, as it features some funny send-ups of Prussian culture and bizarre dark humor—and also because it was first produced just around the corner from where I live, in Milwaukee, in 1891. This “operatic burlesque” might even make for a good piece of over-the-top camp. However, the script contains comedy that would be objectionable today, including gags about a speech impediment and running racist humor about distaste for Blacks—I’m not sure how one could tackle or adapt that. The Berlin comedy Die Prinzessin vom Nil is amusing and could still be effective; there is already a DVD of a performance by the Millowtsch Theater. Perhaps the most promising work deserving rediscovery, however, is the grotesque pantomime Sumurûn written for Max Reinhardt, which was an international success before World War I and was later filmed by Ernst Lubitsch.

Unfortuntely, the reconstruction recently issued on DVD does not use Hollaender’s score.

Are there any more operetta projects coming from you?

Now that this project is off my desk, I want to return to my English-language book on the life and work of Friedrich Hollaender, which has been on hold while this smaller project grew out of it.

For more info, photos and music, click here.

I would like to register my interest in an English version of this biography. It sounds quite interesting.