N. N.

Jacques Offenbach Jahr 2019

18 December, 2018

For the 2019 Offenbach celebrations the city of Cologne has set up a special committee to organize an “Offenbach Year” – offering opportunities for raising the profile of Cologne’s prodigal son in his own hometown, dispel typical clichés and legends, and offer an encounter with long-forgotten works; among them Esther, Queen of Persia by Isaac Offenbach. The organization conducted an interview with Dr. Ralf-Olivier Schwarz, author of the new book Jacques Offenbach: Ein europäischer Komponist and advisor to the Kölner Offenbach-Gesellschaft. In the interview, Mr. Schwarz talks about the project “Offenbach family album,” about the earliest verified Offenbach composition, and about “A civil defense song with chorus” and lyrics by Sternau. So, there is lots to discover!

Jacques Offenbach surrounded by his wife and children.

Dr. Schwarz, what is the “Offenbach family album” exactly?

Between 1830 and 1840 Isaac Offenbach filled a music notebook with the music that he and his family played – at home, for entertainment and other special family occasions. The collection comprises a total of around one hundred pages.

Which members of the Offenbach family used it to play music back then?

According to information noted in the little book, that would be Isaac with his sons Julius and Jacob. But it is plausible that other family member played music as well, especially mother Marianne and the Offenbach daughters. As a rule, the literature consists of songs with guitar accompaniment – Isaac also gave guitar lessons.

How would you classify a find like this? What is special about it?

The family album gives us an intimate insight into the musical daily life at the Offenbach home in the Glockengasse – at a point in time that was highly significant for the compositional development of the youth who would become Jacques Offenbach, that is, the years leading up to his emigration to Paris in 1833.

It is also intriguing to discover that this musical daily life appears to have been anything but one-sided – that applies to the music itself as well as the influences documented in its pages. Among the songs we find recorded there are liturgical pieces for the synagogue, Schubert lieder, French folk tunes, dances, et al. The family album thus provides important documentation of the everyday musical and cultural exchange between Jews and Christian in the early 19th century.

Not to mention the two songs we find there that, according to the handwritten commentary of the young Jacob Offenbach from the year 1831, just twelve years old, are his own compositions – the earliest verified Jacques Offenbach compositions to date.

How could the family music album have gone missing for so long?

The music in the family album was not destined for public consumption. So it seems that after the death of Isaac Offenbach in 1850 no one outside of the family took any interest in it – especially because at that time Isaac’s son Jacques was not yet as famous as he would go on to become. The Offenbach’s youngest daughter Julie presumably took the album with her when, after her father’s death, she left to resettle in the United States.

It took some real sleuthing to find the album. How did you manage to track down the material?

Several decades ago a description of the album had appeared in an English publication, rare and now very hard to get a hold of, and the text basically just outlined the volume, without any reference to its musical significance. This source also gave scant information as to its whereabouts. At the end of the day, it was targeted relentless research in library catalogues that led me to this hodge-podge of papers at the University of Pennsylvania library in Philadelphia. After ordering a facsimile to confirm my suspicions, it soon became clear that I had located the real thing.

The music contained in the Offenbach family album will be performed in a production of the Kölner Offenbach-Gesellschaft within the framework of the Offenbach Year 2019. Performance dates currently under discussion.

The Jacques Offenbach exhibition in Cologne. (Photo: Urban Media Project)

Let’s turn our attention to the likewise rediscovered Purim singspiel ‘Esther, Queen of Persia’ penned by Isaac Offenbach, the father. What is it all about, and who performed it back in the day?

Purim is a Jewish holiday commemorating the survival of the Jewish people under even the most trying of circumstances. However the holiday is traditionally observed with much levity and good cheer. The Purim story centers on Esther, the Jewish wife of the Persian King Ahasver. She manages to foil the evil plans of the mighty Hamam to massacre the Jews, thus saving her people. It is ancient Jewish custom to sing and dance on Purim – and to dress up in costumes, like for the Cologne carnival. Purim plays have also found their way into world literature, beyond an actual Jewish context, in Goethe’s 1773 Jahrmarktsfest zu Plundersweilern, for example.

Comic plays are still performed for Purim today, often in a familial setting at home. They still feature a satirical take on current events – it’s a chance to enjoy letting off steam about all the ills and injustices that irk you. Jerusalem-based theatre historian Jacobo Kaufmann succinctly describes “the cosy, humorous Purim atmosphere” as “the best opportunity for sitting down with your children and giving them important lessons for life in a relaxed, informal manner.”

Queen Esther, a painting by Edwin Long (1879) from the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

That surely reflects the context in which Isaac Offenbach wrote his play Esther, Queen of Persia. The first and it appears only performance took place on 4 March 1833 – it’s not exactly clear where, but presumably at the Offenbach family home in the Glockengasse. The piece – with a cast of six characters supported by a chorus of Israelites – consists of 18 scenes, plus a prologue and an epilogue.

That sounds almost like a real mini-opera. Is this type of domestic musical theatre typical for the period?

This play illustrates a practice that was previously virtually unknown to us: a “house musical theatre” in which serious topics – in this case the life-threatening perils faced by the Jews – are treated with a light, comedic hand. The parallels to Offenbach’s later musical theatre – the sometimes more sometimes less socially critical opéra bouffe – are obvious.

Embedded in the plotline of the play are several songs and choruses previously believed lost. The text has been known for several years, but without the music it seems more like a torso without the limbs, and couldn’t be performed in that state. Prof. Dr. Klaus Wolfgang Niemöller has been able to find (most of) the musical elements, so that the play can now be presented in its entirety.

That piece, too, as you say, was long considered lost – did you have any luck with that search in the USA?

To the best of current knowledge we can reconstruct events as follows: New York cantor Abraham Wolf Binder brought the relevant bundle of source materials to America when he fled National Socialist Germany in the 1930s. It is now housed in the library of the Hebrew Union College in New York. That the play originally contained accompanying music was previously overlooked or not considered, because the only musical notions in the handwritten manuscript are two barely legible melodies scribbled hastily on two pages at the end of the book. This type of notation is a key piece of the convincing evidence for the fact that the musical accompaniment was more or less improvised, based on conventional musical schemata – which makes it relatively simple to reconstruct the musical elements today.

Esther, Queen of Persia by Isaac Offenbach will be performed at Purim in November 2019 in a singspiel staging by the Kölner Offenbach-Gesellschaft. Exact dates TBA.

The Jacques Offenbach exhibition in Cologne. (Photo: Urban Media Project)

A civil defense song penned by Jacques Offenbach? That sounds like a real departure from his prepretoire.

In the face of the revolutionary upheavals in February, 1848 Jacques Offenbach fled with his young family, his wife Hérminie and three-year-old daughter Berthe, to Cologne. He hadn’t been there since 1843 had felt they’d be safe there. But in March 1848, the political turmoil caught up with him. The March Revolution erupted in the German Confederation and would reach the apex of its patriotic and democratic enthusiasm in St. Paul’s Church, Frankfurt, which became the seat of the first German parliament. At the time, democratic civil defense leagues modeled on the French garde nationale of 1790 were forming throughout Germany – as an alternative to the princely law enforcement troops, seen as an instrument of repression. Such a troop formed on 20 March 1848 in Cologne as well.

Finally, on 15 June 1848 a concert given by the Cologne civil defense music corps included the premiere of “A civil defense song with chorus, lyrics by Sternau [pen name of the bookseller C.O. Inkermann who was also active as a political author], in music composed by our compatriot J. Offenbach of Paris”. The text, full of patriotic zeal, reads: “Godspeed to you citizen, comrade / Godspeed to you on your watch, / You walk the true righteous path, / For a divine cause! / A man is false and lacks honor, / if justice he does not observe / But he who protects law and order / Is a German who doth the name deserve!”

Is Offenbach revealing a new stylistic facet here?

TheBürgerwehrlied, or civil defense song is not only a previously unknown, unanticipated documentary evidence of the 1848 revolution in Cologne, in which the democratic enthusiasm in Germany at the time is clearly reflected. We are also confronted with a completely different Offenbach – far from the opera or operetta stage. It also makes clear: had Offenbach been met with a different set of political circumstances, especially in his hometown, perhaps he would never have gone to Paris and become the “inventor of the operetta”, but would have remained in Cologne and become a composer of Romantic choral music. Offenbach’s talent was obviously any -faceted.

What upheavals led to the loss of these musical notes?

Offenbach tried, in 1848, to establish himself in Cologne. He appears to have also been very well connected there. For example, we know that he played a very significant role in the music for that year’s prestigious annual Domfest celebrations in the famous Cologne Cathedral. But due to the significantly more subdued music world, compared to Paris, Offenbach failed to gain a foothold as a composer– an opera composer at that – in the city of his birth. In early 1849 he returned to Paris. In the meantime, the counterrevolution had led to the dissolution of the short-lived civil defense movement. So there was simply no occasion to sing the ‘Civil Defense Song’, which is why it was never published thereafter. But Offenbach kept the manuscript – as he did with all of his compositional material, hording it for possible future re-use.

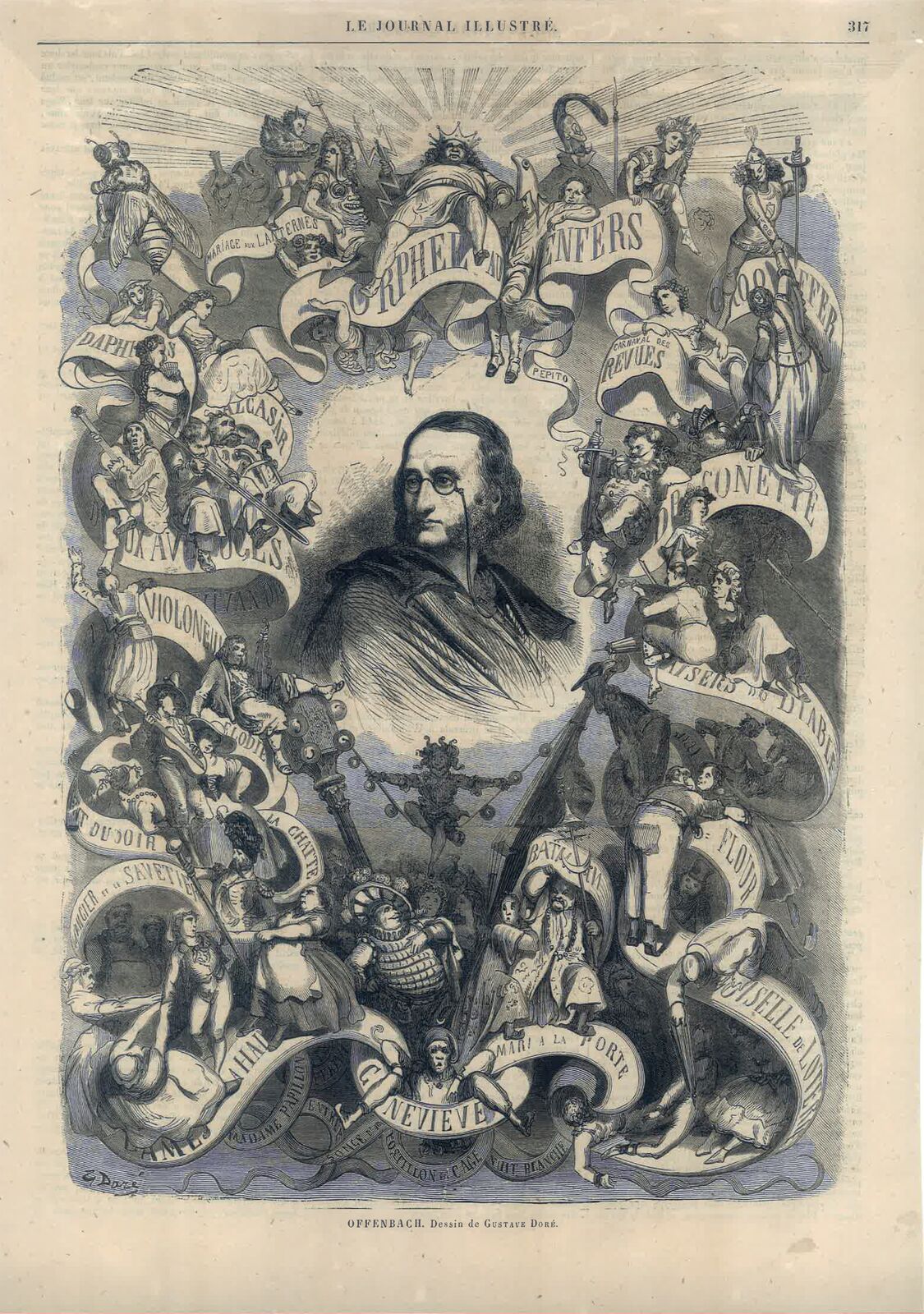

Offenbach as seen by Gustave Doré.

What put you on the trail of the ‘Civil Defense Song’?

The manuscript of the ‘Civil Defense Song’ had been stored along with many other manuscripts from various different collections, in the Offenbach stacks of the historical archives of the city of Cologne. The original went down with the archive building when it tragically collapsed in 2009, but luckily several Offenbach researchers had already made digital copies.

Offenbach’s ‘Civil Defense Song’ will be performed by the Kölner Männer-Gesang-Verein in its annual concert on 22 September 2019 at 11 am in the Kölner Philharmonie.

The Offenbach exhibition (shown on the photos in this article) can be seen from 14 December 2018 to 13 January 2019 at Spanischer Bau, Rathaus Köln; from 26 January to 5 March 2019 at Oper in Staatenhaus, Köln; from 17 May to 31 May 2019 at Salons Aguado, Town Hall 9th Arrondissement, Paris; from 1 June to 15 June 2019 at Oper im Staatenhaus, Köln (in connection with Die Großherzogin von Gerolstein).

For more information on the Offenbach events in Cologne click here.

how fascinating, i had never heard of esther and the tradition of funny purim plays (and in this case by father isaac). danke – most illuminating dr schwarz´explanations about the offenbach family album. gh

How did I miss this? Sounds fascinating!