Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

15 March, 2020

When the world is under quarantine and everything is shut down because of a new virus – you have lots of free time to listen to music at home. (If you are so lucky.) Because of the recent controversial premiere of Offenbach’s Die Banditen at Staatsoperette Dresden (announced as “Falsacappas megageile Banditenshow”), I took some of my old Les Brigands recordings out of the shelf and listened to them again. While I was hopping from one disc to the next I discovered two German versions that I had heretofore not noticed and that I’d call some of the best Offenbach ever put on disc: one is from Hamburg 1958, the other also from Hamburg 1961. The standout in the first is the conductor Richard Müller-Lampertz, the other has Helge Rosvaenge as Falscappa. Both recordings are in German using the old Viennese translation by Ernst Dohm, and both leave the French competition far behind.

A scene from the 2020 production of “Die Banditen” by Valentin Schwarz at Staatsoperette Dresden. (Photo: Pawel Sosnowski)

If you only know the various Franz Marszalek recordings as examples of post-WW2 German operetta tradition or the EMI series with Rothenberger, Gedda et al, then these two Banditen from Hamburg will come as a surprise. Because they sound entirely different and are cast in a way far removed from the sterile EMI “Spielopern” approach.

Let’s start with the 1958 version. I hadn’t noticed it before because it’s sandwiched into a highlights double disc with Die Kreolin before and La Jolie Parfumeuse/Pariser Parfüm and La belle Lurette/Die schöne Lurette afterwards. I was actually playing Kreolin recently when I sat up listening to the first Banditen track. The orchestra sounds so crisp, the conducting has so many detailed accents and such energy, that I had to check who the conductor was. His name: Richard Müller-Lampertz, who also does Kreolin and Pariser Parfüm.

The Cantus Classics edition of “Die Banditen,” combined with other Offenbach shows. (Photo: Cantus Classics)

His name didn’t ring a bell, but what you get is an Offenbach interpretation that has few equals. Certainly when you compare this kind of conducting with John Eliot Gardiner or Marc Minkowksi’s recent Offenbach efforts. Here, there is a full symphonic sound handled with delicacy and nuance. And with an ability to constantly surprise the listener by following Offenbach’s dynamic markings to the max, and by giving the music a flexibility you won’t find in Gardiner/Minkowski. Especially when it comes to the finali and the ability to shift gears and send the music into (controlled) overdrive.

Add to this a cast of character singers that are not interchangeable but really pin down their roles. Toni Blankenheim as a tenor Fragoletto is probably the best-known name, but Reinhold Barthel as Falsacappa is equally convincing.

The ladies are all noticeably light sopranos and mezzo-sopranos, highly distinguishable. They bounce through their music with ease and joy, and humor. (Erna Maria Duske as the Herzogin von Alca is hilarious, by the way.)

Sadly, there are only seven numbers on this highlights disc. I looked online if Cantus Classics might have released a full recording – of what clearly was a full radio production – elsewhere. But nothing popped up. Which is a real shame. But these seven tracks are must-have! (They sound better on disc than on YouTube, don’t ask me how that is possible; there’s none of that bizarre echo.)

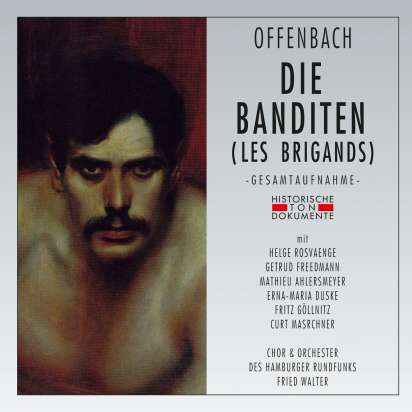

The 1961 recording of “Die Banditen” with Helge Rosvaenge. (Photo: Cantus Classics)

The 1961 version from Hamburg is also a radio broadcast, it spreads out onto two discs. The source material is questionable, especially on disc two (i.e. act 2 and 3) you hear the station falling out of focus and overlapping with a second classical concert. Unless you’re a fan of modern music where such layering is progressive you’ll find it highly irritating.

It’s a pity that Cantus Classics haven’t managed to get the original recording out of the Hamburg radio archive and issue this properly. Probably, they don’t want to pay the charges involved and opted for a shady copyright-free alternative based on someone’s private tape.

A scene from the 2020 “Die Banditen” at Staatsoperette Dresden, with a female Fragoletto. (Photo: Pawel Sosnowski)

That said, the conductor here is Fried Walter. Another name unfamiliar to me, but another musician who knows how to give real life to proceedings. There’s none of the “quaint” and “pseudo-classical” conducting you encounter with Willy Mattes et al, this is full-blooded theater music, not a Wunschkonzert. Mr. Walter is not as overwhelming as Richard Müller-Lampertz, and he is sometimes a bit liberal with Offenbach’s markings, but the results are convincing. With some particularly grandiose moments at the end of the acts and big ensembles.

He has a superstar cast at his disposal. Again, there’s a tenor Fragoletto. (It seems post-WW2 Germans were afraid of breeches roles – maybe because that would have made operetta too lesbian?) Here the young Peter Minich gives an outstanding performance that is equal to the other famous German version on RCA where Jean van Ree is Fragoletto in 1981.

In his Musical Theatre on Record Kurt Gänzl writes about Mr. van Ree: “He has an easy, light tenor voice with an almost feminine (but not effeminate) sweetness to it which is ideally suited to Offenbach’s mezzo-soprano music; he flips trippingly through his delicious saltarello in a way that usually only the most mobile of feminine voices can, and takes part very effectively in the many delightfully accurate and pointedly performed ensemble portions of the show.” You can apply this 1:1 to Peter Minich, only that the conducting is better here. Alas, the sound quality is not.

Again, the ladies are on the light side, representing a lost German soubrette tradition that enchanted audiences for years and that has fallen completely out of fashion today.

The tenor Helge Rosvaenge in a early fan postcard.

The stand-out performance comes from Helge Rosvaenge, very late in his career. It really is a one-of-its-kind interpretation because I know of no other Falsacappa on disc who plays with the music in such a way and acts through the music like Mr. Rosvaenge. He, too, represents a lost tradition of delivering crystal clear lyrics with great dramatic oomph, and employing everything in his power to create a memorable character. That’s obvious from the start. As Falsacappa comes in with two (deliciously stupid sounding) soubrettes complaining about the “difficult road of virtue,” Rosvaenge replies in a winy mezza-voce voice, only to pull all his Heldentenor stops out as he unmasks himself. When Rosvaenge hits those notes-of-revelation, there is no competition.

In this opening scene he has Mathieu Ahlersmeyer by his side as one of the bandits. Mr. Ahlersmeyer also started his operatic career in Nazi times and made many recordings for the radio before 1945. He, too, knows how to create a character with only two lines to sing. It’s astonishing and wonderful to hear him!

There are moments you won’t find like this anywhere else. The big canon in act two (“Give us bread/Date panem”) is sung in such a grotesque way that you almost fall off your seat laughing.

And the police officer with his troops (a performer not listed on the sleeve of the recording) give another one of those once-in-a-lifetime renditions.

Another scene from the controversial Staatsoperette Dresden production of Offenbachs “Die Banditen.” (Photo: Pawel Sosnowski)

Considering the political climate in Germany in the early 1960s – ultra-conservative and with a forced silence about everyone’s Nazi past, right up to the highest political and social ranks, such as the police and government – makes the tone this head of police employs spooky. In a way that’s probably lost on a younger generation of listeners not familiar with German social life that erupted in the 1968 revolts, because of exactly this kind of stilted self-righteousness by the police.

All of these things are aspects you won’t find on later recordings. Certainly not on any of the French versions. Unless you count the seven historical tracks that have been included in the Offenbach Anthology, volume 3. A particular favorite of mine on that anthology is Dranem singing “O mes amours, ô mes meîtresses”, with an orchestra conducted by Gustave Cloéz. It’s superb!

Talking of which: On the better- known 1981 German version conducted by Pinchas Steinberg with the forces of WDR radio chorus and orchestra (with Jean van Ree singing Fragoletto) you get two unusual performances that set this version apart. First, and most obviously, there’s a female Antonio, the wicked treasurer. It’s sung by Evelyn Künneke (yes, daughter of Eduard). Her version of “Sagt mir ein Weib, dass ich es liebe” can stand up to Dranem and is a ideal example of a husky cabaret singer delivering lines. Kurt Gänzl calls it “a spendidly comical diseuse portrayal” that sounds “suitably mannish.” Indeed, it does.

The other unusual portrayal comes from Gerd Vespermann as the Prince of Braganza. He delivers an ultra-camp version of the prince’s 3rd act song (“Einst herrscht in fernen Landen”) about the amorous infidelities at court. And he’s got Martha Mödl and Marita Knobel as his ladies in waiting. In other words: it’s uproarious. With each verse building up the fun and final punch line. And it shows just how effective a non-operatic voice is when it comes to transporting subtext and getting the (sexual) jokes across.

All in all that Steinberg version on RCA (Capriccio on CD) is technically the best. If you want a female Fragoletto there’s no way around the Gardiner version (with Colette Alliot-Lugaz singing the part).

But surprisingly the older German conductors deliver the more energy driven and artistically interesting interpretations, even if they don’t have the advantages of digital stereo sound.

In an ideal world you’d combine all of the above into one single performance – or have a record company that secures a proper original tape and restores it with loving care. Cantus Classics is not that company. But still, their releases are worth having and well worth listening to, again and again.

I, for one, have had enormous fun with all these historic Banditen galloping through my living room. Probably more fun than I would have had with the live Banditen at Staatsoperette – which now are under quarantine. (All theater performances in Germany have been cancelled till after Easter, at the very least.)

For more information on the Dresden production and (possible) future performance dates, click here.