Richard C. Norton

Glitter and be Gay/Operetta Research Center

1 September, 2007

Noël Coward (1899-1973) and Ivor Novello (1893-1951), both English, both homosexual, were the two most enduring proponents of English language operetta in the twentieth century. How their sexuality informed their work, and the extent to which it shaped their careers, is a fascinating area of study today. Both men emerged as “bright young things” in the West End revues of the late 1910s and early 1920s. While Coward and Novello were always privately known to be homosexual within the professional theatre community, the general public and the press respected their personal privacy and accepted their outward pretense of heterosexuality as a plausible fiction. As a professional prerequisite to any career in theatre, both Coward and Novello cultivated their public reputations as elegant, witty or romantic figures, and surrounded themselves with talented men and women. Although often publicly photographed with women, neither man seriously considered marriage, and both engaged in long-term homosexual relationships. As professional peers and amiable rivals, Coward and Novello held one another in high esteem, and there is nothing in their work or private papers to suggest that they were anything but professional peers, creative rivals and good friends.

Actor and author Noël Coward, in the 1930s.

Coward began first as a child actor, and he immersed himself exclusively in the backstage culture of theatrical auditions, rehearsals, greasepaint, chorus girls, spotlights, revue sketches, concert parties, etc. First discovered by Andre Charlot, intimate revue’s greatest exponent, Coward collaborated with Roland Jeans on sketches for Charlot’s revue, LONDON CALLING (4 September 1923, Duke of York’s, 316 performances). Its Music and lyrics were however strictly Coward’s. Its success propelled him to pen sketches, music and lyrics for several archetypal musical revues, ON WITH THE DANCE (30 April 1925, London Pavilion, 229), THIS YEAR OF GRACE (22 March 1928, London Pavilion, 316) and WORDS AND MUSIC (16 September 1932, Adelphi, 164). What was radical about Coward was his unprecedented capacity as sole author, whereas previously revues had typically been collaborative affairs, a collage of songs and sketches by an assortment of two or more writers. Coward also wrote plays that broached social taboos, such as THE VORTEX (1924), which depicted drug addiction and mother fixation, and DESIGN FOR LIVING (1933), which dazzled its audience with an openly sexual ménage á trois.

Having conquered the West End with revue, “slightly daring” drama and light comedy, Coward set himself the daunting task of writing a lavish and romantic operetta with BITTER-SWEET (18 July 1929, His Majesty’s, 728 performances). Whereas musical comedy with its jazz and dance band melodies had largely usurped operetta in London’s West End in the 1920s, BITTER-SWEET was an unabashed return to sentiment, spectacle and sweeping melody. By Coward’s own admission, Johann Strauss’ DIE FLEDERMAUS inspired Coward’s story of a privileged young woman, Sarah Millick, whose love for Carl Linden, her penniless music teacher, leads her to elope with him to Vienna. Forced to earn their living at a second-rate café, Carl dies defending her honor from the amorous entreaties of Captain Lutte. Sarah lives out her days as the world-famous singer, Sari, sustained by the memories of her young love. Now an older woman, Sari’s story is framed by a present-day (1929) prologue and epilogue in which she admonishes a young woman to follow her heart, not her head. The musical score introduced three of Coward’s most enduring songs, “If Love Were All,” “I’ll See You Again” and the faux-Viennese “Zigeuner.” Less known is Coward’s quartet of aesthtes singing of “(We All Wore a) Green Carnation”:

“Pretty boys, witty boys, too, too, too

Lazy to fight stagnation

Haughty boys, naughty boys, all we do

Is to pursue sensation.

The portals of society are always opened wide

The world our eccentricity condones

A note of quaint variety we’re certain to provide

We dress in very decorative tones.

Faded boys, jaded boys, womankind’s

Gift to a bulldog nation

In order to distinguish us from less enlightened minds

We all wear a green carnation.”[1]

“Green Carnations” is both a burlesque of the excess of the dandy and aesthete, but also an unabashed celebration of homosexual style, with for its time, a daring wink and a nod. Although Coward was writing primarily for the general (i.e. heterosexual) theatre-going public, he could mock more aggressively flamboyant homosexual behavior, and thereby stake his claim to the sophisticated, worldly witty center. In this way, Coward perpetuated his own “closet,” his own private homosexual existence forever at odds with his public persona.

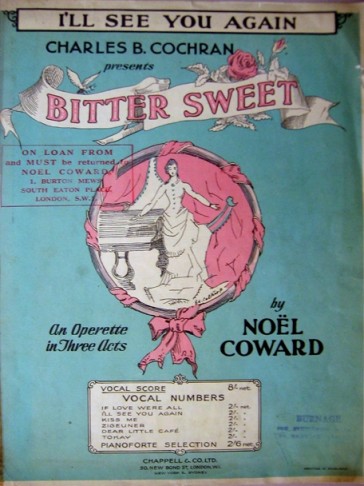

“I’ll See You Again”, the hit song from “Bitter Sweet” in a sheet music version.

Although BITTER-SWEET triumphed in its initial London run of 22 months, it had the misfortune to premiere in New York at the cusp of the Great Depression. Opening one week after the New York stock market crash, its acclaimed New York run (5 November 1929, Ziegfeld, 157) was cut short by the collapse of the Broadway theatre-going economy. Although presented in Budapest as RÉGENE ÉS MOST (6 December 1929) and Paris as TEMPS DES VALSES (2 April 1930), BITTER-SWEET’s enduring reputation stems from its two film versions (UK, 1933, and an American MGM corruption[2] with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, 1940), and its hit songs which have outlasted the popularity of the show itself.

Concurrent with BITTER-SWEET’s triumph, Coward opened and starred in his most famous play, PRIVATE LIVES (24 September 1930, Phoenix, London, 101; 27 January 1931, Selwyn, New York, 256), opposite his frequent muse, Gertrude Lawrence. Although the play contained but one enduring song, “Someday I’ll Find You,” PRIVATE LIVES captured the privileged life of an irreconcilably divorced couple who find themselves in adjoining suites on the improbable occasion of their honeymoon with their new spouses. At a time when divorce was still thought scandalous, Coward once again mocked and then celebrated modern mores, by reuniting the tempestuous couple, and compelling them to abandon their dullish partners. Whereas operetta may not illustrate Coward as the social rebel he dared to be in his plays, its traditional conservative form presented a mainstream heterosexual cover, or “beard,” which afforded him security, privacy and success. Note that the traditional message of BITTER-SWEET, “to follow one’s heart,” suggests that true happiness comes not from an arranged marriage within one’s own social class, but from an independent spirit willing to rebuke the conventions of society. By inference, the independent hero/heroine could choose a homosexual lifestyle, even if it is private and sheltered from public view. As a poor gay boy who created his own public hetero persona of wit and privilege and would in his final years be knighted Sir, Coward would return again and again to his theme of the outsider, or lower class, bumping up against the rules and prejudices of the upper class. Following PRIVATE LIVES and BITTER-SWEET, Coward penned a historical pageant with music, CAVALCADE (13 October 1931, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 405), which cemented his fame as an English patriot, sentimental historian and guardian of the fading British Empire.

Inspired by the success of his first operetta, Coward wrote four more, none of which ever matched the success of BITTER-SWEET. First among them was CONVERSATION PIECE, a Regency era (circa 1811) vehicle for French actress Yvonne Printemps (16 February 1934, His Majesty’s, 177). Printemps (who spoke virtually no English) played a French singer Melanie in search of a wealthy English husband in Brighton. Coward himself played the impoverished Duc de Chaucigny-Varennes, who wins Melanie’s heart despite the entreaties of many wealthier suitors. By presenting the reigning doyenne of the French musical stage in London in his own custom-built vehicle, Coward was determined to breathe new life into the genre of operetta. More of a comedy with incidental songs, CONVERSATION PIECE suffered from the weight of its social banter, lavish production, few songs, and the language limitations of its star. Indeed Coward assumed the male lead role when Romney Brent proved unsatisfactory in rehearsals. When later during the run, Pierre Fresnay, Printemps’ true-life companion assumed the role of Paul, attendance fell off, and Coward was compelled to resume the role. CONVERSATION PIECE had but a forced seven-week run with its original stars in New York, and has been seldom seen or heard since. The score yielded one enduring gem, “I’ll Follow My Secret Heart,” and the libretto’s romantic theme, of true love transcending class or wealth, is wearily reminiscent of BITTER-SWEET.

The one and only Fritzi Massary.

Coward’s persistent devotion to the operetta form faltered in the face of serious competition from his chief rival, Ivor Novello, whose four consecutive operetta spectacles dominated the West End’s largest stage, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, for five years beginning in 1935. With Coward’s next offering, OPERETTE (16 March 1938, His Majesty’s, 133), he once again imported a famed international star, Fritzi Massary, former darling of Berlin’s operette stage, for London’s delight. Following her last success in Oscar Straus’ EINE FRAU, DIE WEISS, WASS SIE WILL (1932), Massary fled Germany, heralding the end of Berlin’s silver operette era. Coward tailored a romantic story which reiterated the plot themes and devices of his previous two shows. Massary appeared as Vienna stage star Leisl Haren, whose musical counsel prevails when aristocratic youth Nigel Vaynham (played by Griffith Jones) wants to wed former chorus girl Rozanne Grey (Peggy Wood). Rozanne was now starred in “The Model Maid,” OPERETTE’s show-within-a-show, which afforded Coward the opportunity to write an homage to the Edwardian operettas of his youth, FLORODORA and its famous sextet, and the musicals of the Gaiety stage. This production was presented by John C. Wilson, Coward’s romantic and sexual partner at the time. Although its lyrical ballads and soprano solos were charming if swiftly forgotten, the one song to endure is yet another male quartet, “The Stately Homes of England,” which tweaks the idiosyncracies of the upper classes.

Back to Broadway, John C. Wilson presented Beatrice Lillie in an all-Coward revue known as SET TO MUSIC (18 January 1939, Music Box, 129), which included songs and sketches previously seen and heard in London (“Mad About the Boy”) and some new material (“I Went to a Marvelous Party”). Earlier in Bea Lillie’s revue career, this virtuosic and brilliant comedienne often performed “trouser” roles, and her deadpan comic timing made lyrics such as these sparkle:

“I went to a marvelous party,

We didn’t start dinner till ten

And young Bobbie Carr

Did a stunt at the bar

With a lot of extraordinary men;

Dear Baba arrived with a turtle

Which shattered us all to the core,

The Grand Duke was dancing a foxtrot with me

When suddenly Cyril screamed “Fiddldedidee”

And ripped off his trousers and jumped in the sea,

I couldn’t have liked it more.” [3]

Coward penned an additional lyric to “Mad About the Boy” for a conservatively dressed businessman to sing, but it was discarded before production:

“Mad about the boy,

It’s most peculiar but I’m mad about the boy.

No one but Doctor Freud could have enjoyed

The vexing dreams I’ve had about the boy.

When I told my wife

She said she’d never heard such nonsense in her life.

Her lack of sympathy

Embarrassed me

And made me, frankly, glad about the boy!

My doctor can’t advise me,

He’d help me if he could;

Three times he’s tried to pyschoanalyze me

But it’s just no good.

People I employ

Have the impertinence to call me “Myrna Loy”,

I rise about it

Almost love it,

For I’m absolutely mad about the boy!” [4]

Poster for the film version of “Blithe Spirit”, starring Rex Harrison.

Coward’s greatest war-time success was not an operetta but a light comedy of ghosts and marital squabbles, BLITHE SPIRIT (2 July 1941, Piccadilly, 1997). Unable to bear arms in WW2, Coward burnished his patriotic reputation by writing the screenplay to IN WHICH WE SERVE, a potent piece of wartime propaganda, and by touring Africa, Europe and the Far East with ENSA, the British government’s wartime travelling live entertainment agency. When the management of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, planned to re-open after the war, they turned however not to Novello, but to Coward with a commission for PACIFIC 1860. Once again Coward imported a celebrated star, Mary Martin, whose successes in American musical comedy (“My Heart Belongs to Daddy,” in Cole Porter’s LEAVE IT TO ME, 1938, and “Speak Low,” in Kurt Weill’s ONE TOUCH OF VENUS, 1943) made for improbable casting as a visiting opera star, Elena Salvador. Set on the fictional South Pacific island of Samolo, Elena Salvador falls in love with Kerry Stirling (Graham Payn), son of a local ex-patriot family. True love finally triumphs over their disparate social classes, Coward’s indispensable favorite plot. However, the romance of PACIFIC 1860 never compelled excitement, while the male novelty patter songs “His Excellency Regrets” and “Poor Uncle Harry” (a close cousin to “Mad Dogs and Englishmen”) have outlived the score’s now forgotten sentimental ballads. With the demise of Coward’s PACIFIC 1860, the path opened up to the Drury Lane for Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! to take the West End by storm, whereby musical comedy dealt operetta a death blow.

Coward first met the boy soprano, juvenile actor Graham Payn (1918-2005), when he auditioned for his West End revue WORDS AND MUSIC (1932), in which he performed minor roles and the busker in the soon-to-be-famous “Mad About the Boy.” Introduced as a quartet by Joyce Barbour, Norah Howard, Steffi Dunn, Doris Hare, “Mad About the Boy” was performed as an homage of unrequited love to the contemporary male movie stars of the day. Those lyrics proved prophetic, when thirteen years later on March 30 1945, at his luncheon table Coward found himself ‘mad about the boy’ Graham Payn:

“Mad about the boy,

It’s pretty funny but I’m mad about the boy,

He has a gay appeal

That makes me feel

There’s maybe something sad about the boy.”

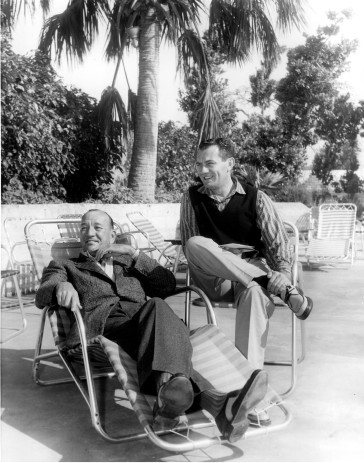

Coward with his life-partner Graham Payn.

A serious romance started, and Payn moved in with Coward two years later. Coward did his utmost to secure stardom for Payn, featuring him in his own revue SIGH NO MORE (1945), for which Coward penned the tender song “Matelot,” a sailor’s call to the sea. Seizing upon the press’ modest praises, Coward unwisely starred Payn in PACIFIC 1860 (1946), a Broadway revival of TONIGHT AT 8:30 opposite Gertrude Lawrence (1948), ACE OF CLUBS (1951), AFTER THE BALL (1954) and WAITING IN THE WINGS (1960). Coward’s unremitting sponsorship of Payn’s career was a transparent declaration of his love to all the world. But that love was blind, for neither the critics nor public thrilled to Payn’s talent, and Coward was finally forced to concede that Payn lacked both star quality and the requisite ambition. Nicknamed Little Lad by Coward, the fiercely loyal Payn joined Cole Lesley and Joyce Carey as part of Coward’s devoted entourage, and survived Coward by 34 years. Late in life Coward was affectionately known to this inner circle as “the Master.”

Some newspaper critics, the Daily Mail’s Michael Thornton among them, claim that Payn’s dependence, alcoholism, promiscuity, and lack of talent, diminished Coward’s later reputation. In a newspaper article one week after Payn’s death, Thornton[5] quotes Sir Ian Fleming’s widow Ann: “Darling, he was, you see—how shall I put this— rather well-endowed. I know because they were forever sunbathing in the nude. I can only suppose that he must have been quite accomplished in bed. He certainly had nothing else to recommend him.” Some friend she was to Coward! An independent reading and critical appraisal of Coward’s plays and musicals (1945-1966) suggests that The Master’s most imaginative work preceeded Graham Payn’s arrival; without Payn in the productions’ cast, it’s doubtful that PACIFIC 1860 or ACE OF CLUBS would have been any more successful. As beneficiary of Coward’s estate and keeper of the flame, Payn may nonetheless be widely credited with keeping Coward’s name and work in the public eye after his death in 1973.

With operetta in eclipse, Coward wrote a brash musical comedy ACE OF CLUBS for his protégé Graham Payn, who starred (again!) as a sailor Harry Hornby in pursuit of a nightclub singer Pinkie Leroy (played by Pat Kirkwood) in London’s sleazy Soho district (7 July 1950, Cambridge, 211). A less than plausible plot about gangsters and stolen jewels attached to an unpersuasive romance delivered Coward yet another flop. Yet the infectious swing of Kirkwood’s “Chase Me, Charlie,” Payn’s pensive ballad “Sail Away” and the irrelevant yet jaunty “I Like America” pleased Coward loyalists, while the author wrote yet another male trio, “Three Juvenile Delinquents,” satirizing indolent youth and lax judges. Coward attempted to bestow upon Graham Payn’s Harry some sex appeal:

“There’s always something about a sailor,

Nobody’s ever able to define,

There’s a gay—salty sort of tang about

His devil may care,

His nautical air

Of brawn and brine.” [6]

Coward’s last operetta, AFTER THE BALL (10 June 1954, Globe, 188), musicalized Oscar Wilde’s celebrated comedy of manners LADY WINDERMERE’S FAN, to generally disparaging reviews. Returning to his favorite Edwardian period, Coward was drawn to Wilde’s story of social outcast Mrs. Erlynne (operetta doyenne Mary Ellis) salvaging the reputation of Lord Windermere’s wife. The combination of Noël Coward and Oscar Wilde’s wit ought to have been sublime and delicate, but instead proved dull and old-fashioned.

If Coward’s play- and song-writing efforts no longer garnered much public or critical enthusiasm, he discovered unexpected success as a solo performer in the early 1950s. At the annual June Theatrical Garden Party charity fundraiser, Coward had modestly performed several half hour sets with Norman Hackforth as his accompanist. This led to a booking at London’s fashionable Café de Paris 29 October 1951, and Noël Coward was re-born as the most witty, elegant and entertaining of cabaret performers. Drawing on his own catalogue of standards (“I’ll Follow My Secret Heart,” “If Love Were All,” “Mad Dogs and Englishmen,” “Someday I’ll Find You,” “I Went to a Marvelous Party”), Coward further popularized other lesser-known patter songs (“(Poor) Uncle Harry” and “Alice is at It Again”) and ballads from his revues and operettas. England’s extortionate post-war income tax rates inspired him to accept a most improbable offer to appear in Las Vegas in June 1955 at the Desert Inn. When Hackforth’s work visa was denied, Marlene Dietrich recommended a young arranger Peter Matz who re-orchestrated Coward’s oeuvre for American tastes. Since Las Vegas was still an exclusive playground for the wealthy and not the mass market vacation venue it has since become, Coward penned new and naughty lyrics to Cole Porter’s standard “Let’s Do It” which were customized to the celebrity audiences which crowded to see and hear him.

“In Texas some of the men do it

Others drill a hole—then do it,

Let’s do it, let’s fall in love.

West Point cadets forming fours do it,

People says all those Gabors do it,

Let’s do it, let’s fall in love.” [7]

Most of Coward’s plays of this period, SOUTH SEA BUBBLE, QUADRILLE, NUDE WITH VIOLIN, LOOK AFTER LULU, and WAITING IN THE WINGS all met with disappointingly short runs. Coward’s last two musicals, not operettas, were accorded brief runs in New York: SAIL AWAY!, 3 October 1961, Broadhurst, 167; THE GIRL WHO CAME TO SUPPER, 8 December 1963, Broadway, 113. The latter had the misfortune to arrive shortly after the assassination of President John F Kennedy; indeed, its opening number, a spoof of assassination “Long Live the King if He Can” was quietly replaced. SAIL AWAY! later managed a modest seven-month run in London (21 June 1962, Savoy, 252). Coward had difficulty reconciling the revolutions of the 1960s. He abhorred the rock music of the Beatles, deplored playwright John Osborne’s angry young men, and refused to accept changing social and sexual mores. Then unpredictably, Coward was “rediscovered” in the unlikeliest of quarters: London’s National Theatre revived his play HAY FEVER in 27 October 1964 with a stellar cast of Dame Edith Evans, Maggie Smith, Robert Stephens, Derek Jacobi and Lynn Redgrave. Coward’s reputation rebounded with a new critical regard for his oeuvre. Meanwhile Coward wrote his last dramatic effort, SUITE IN THREE KEYS, a dramatic triptych whose A SONG AT TWILIGHT dramatized a Coward-like writer’s reunion with a past mistress. Its veiled self-portrait[8] illiminated Coward’s private demons, when the writer’s mistress reveals she has his private love letters, saying “You’ve been homosexual all your life, and you know it!” The paranoid threat of public exposure, ridicule and prosecution as a homosexual, such as that suffered by Oscar Wilde in the 1890s, John Gielgud in 1953[9], and journalist and playwright Peter Wildeblood in 1954[10], forever haunted Coward’s imagination. His performance as SONG AT TWILIGHT’s hero Sir Hugo Laytmer was widely admired by some writers and loyalists, and derided as a feeble admission of weakness by other modern critics.

On the occasion of his 70th birthday, the honor of a Knighthood which had so long eluded him, was finally bestowed upon Coward. Although Coward had always been on cordial terms with Britain’s royal family, he imagined the reluctance to grant him a knighthood stemmed from his own homosexuality, or else the long-standing rumors of his dalliance with Prince George, Duke of Kent, in the 1920s[11]. That spring 1970, the Coward renaissance continued to snowball with a wildly popular American revival of PRIVATE LIVES starring Brian Bedford and Tammy Grimes; in spring of 1971 he received an honorary Tony Award for distinguished achievement in the theatre. For the first time without Coward’s active particpation, new revues were assembled to showcase the Master’s lifetime work, the most successful being COWARDY CUSTARD and OH, COWARD! Thus honored and fêted, Coward died at his beloved home in Jamaica, Firefly, on 26 March 1973. Although the first authorized biographer Sheridan Morley lobbied Coward to disclose his sexuality, Coward staunchly declined, and it was left to later biographers to explore its implications. Alone among his operettas, BITTER-SWEET received its only full-scale London revival courtesy of Sadler’s Wells in February 1988; with the original orchestrations now lost, it received its most complete recording from TER/That’s Entertainment Records.

The Romantic Competitor: Ivor Novello

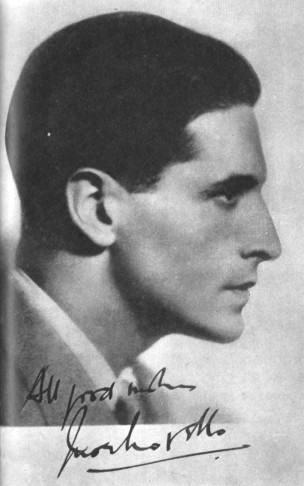

A dashing looking young Ivor Novello in a typical publicity shot.

Six years older than Coward, Ivor Novello was born to greater privilege, and found in his mother Clara Novello Davies, a dynamic proponent of his early musical talents. Beginning in 1910 at the precocious age of 17, Ivor Novello’s first published compositions were concert or parlor songs in a light classical vein. His mother was a tireless advocate and conductor of choral singing; when Ivor’s adolescent voice broke, he abandoned voice and determined above her objections to seek a career for himself composing for and acting in the theatre. Yet no one could have imagined his extraordinary luck four years later in composing WW1’s most famous song, “Keep the Home Fires Burning,”[12] with lyric by poet Lena Guilbert Ford. Its success granted him immediate access to music publishers, theatre producers and performers, who eagerly sought his songs for revues. The stars of West End operettas and musicals, Gertie Millar, Lily Elsie, Phyllis and Zena Dare, became his heroines and then friends, and Novello penned melodies (along with American Jerome Kern) for THEODORE AND CO (14 September 1916, Gaiety, 503), and SEE-SAW (14 December 1916, Comedy, 158). Novello interpolated seven additional songs into a previously French musical comedy ARLETTE (6 September 1917, Shaftesbury, 260), wrote half the score with Howard Talbot for WHO’S HOOPER? (13 September 1919, Adelphi, 349) and the complete score for THE GOLDEN MOTH to mostly P G Wodehouse lyrics (5 October 1921, Adelphi, 281), all hugely successful in their time yet totally forgotten today. For legendary revue producer André Charlot, Novello was the sole composer for the revue TABS (15 May 1918, Vaudeville, 268) which starred Beatrice Lillie, and co-composer with Philip Braham of A TO Z (21 October 1921, Prince of Wales, 428), which yielded arguably his most famous comic song, “And Her Mother Came Too” with lyrics by Dion Titheradge.

If one considers Novello himself as a man famously tethered to his domineering mother, Titheradge’s enduringly funny lyric about a young man’s fiancée’s ubiquitous mother has an unmistakeably gay appeal even today. First introduced in the show by Jack Buchanan, known to be homosexual by theatrical insiders:

“We lunch at Maxim’s,

And her mother comes too!

How large a snack seems

When her mother comes too!

And when they’re visiting me,

We finish afternoon tea,

She loves to sit on my knee—

And her mother does too!

To golf we started, and her mother came too!

Three bags I carted

When her mother came too!

She fainted just off the tee,

My darling whispered to me—

Jack dear, at last we are free!

But her mother came to!”

Novello’s greatest attribute was his strikingly handsome face and profile combined with instinctive stage skills, which led him to swift stardom in silent film (THE CALL OF THE BLOOD, 1920) and on the West End stage (Sacha Guitry’s DEBURAU, adapted by Harley Granville-Barker, 23 November 1921). Fifteen additional silent film star roles affirmed Novello’s status as screen heart-throb, while he starred in twelve additional plays in the West End, one of which (the disastrous SIROCCO) was written by Noël Coward, and two of which (THE RAT and DOWNHILL) he wrote with Constance Collier under the pen-name David L’Estrange. Set in a Paris cabaret, the White Coffin, Novello was THE RAT, “and six or sixteen or sixty lovely ladies in the cast kiss him with intention at and between the various curtains, and he dances, and laughs, and slays, and makes love, and even goes mad and babbles of green fields, and the audience is swayed by his joys and sorrows, and it is all incredibly humiliating to the intelligence and exciting to the emotions of the crowd. It must be seen to be believed.”[13] Thus was set the dramatic cliché of the romantic hero, which was to be Novello’s life-long mantel. “David L’Estrange’s” next play DOWNHILL starred Novello as a man unjustly accused of fathering a child, driven to destition and near suicide, until his name is cleared at last. Novello’s first solo play produced under the pen-name ‘H. E. S . Davidson”—despite the fearful objections of his friends and Noël Coward—THE TRUTH GAME showed Novello as Max Clement, a handsome yet penniless adventurer, courted by a wealthy widow. A major West End success (5 October 1928, Globe, 162, London; 27 December 1930, Ethel Barrymore, New York, 107), THE TRUTH GAME affirmed Novello’s status as triple threat: not only was he composer, actor and star, but now also playwright.

This melodramatic formula assured popular success for Novello, even though some critics sneered, and he next authored SYMPHONY IN TWO FLATS, (14 October 1929, New Theatre, London, 158; 16 September 1930, Shubert, New York, 47), in which he starred as David Kennard, a struggling classical composer who loses his sight, almost loses his young wife to a rival lover, and must stoop to write popular songs to survive.

Critics carped at its sentimental contrivances, but the (mostly female) public flocked! Novello spent but a brief sojourn in Hollywood writing the tepid fim version of THE TRUTH GAME released as THE FLESH IS WEAK. In the days before Hollywood’s production code, note the salacious title promising more than the film itself delivered. Ivor wrote the screenplay for LOVERS COURAGEOUS, penned a couple of lines for Greta Garbo in MATA HARI, but wrote dialogue for one classic screenplay for MGM, the first talkie of TARZAN, THE APE MAN. Starring bare-chested Olympic athelete Johnny Weissmuller, MGM’s 1932 feature TARZAN must rank among the most celebrated beefcake features ever. Who else but Novello could transform Edgar Rice Burrough’s narrative into the now classic exchange “Tarzan—Jane! Jane—Tarzan! Tarzan—Jane!” This unexpected hit for MGM spawned a whole series of sequels, but Ivor returned to London’s West End which he preferred to the sunny palms of Hollywood.

Novello’s long-term companion was the successful West End dramatic actor Robert Andrews (1895-1976), whose first role in a Novello play was that of Tim Crabbe in FRESH FIELDS (1932), followed by the frustrated lover and murderer Bill Sherry in MURDER IN MAYFAIR (1934). Novello and Andrews first met in 1916-17, and were lovers until Novello’s death. Unlike Coward’s protégé Graham Payn, Andrews had secured steady stage employment for himself since age 11, and need not rely upon Novello for work. James Agate in the [London] Sunday Times offered this appraisal of Andrews’ limitations: “Mr. Andrews is always a much better actor than anybody supposes… But the leopard cannot change his spots, and vice versa! What I mean is that this actor has bounced up and down with a tennis racket on too many of Marie Tempest’s sofas to steep his hand in murder. And perhaps after all it didn’t matter who killed the slut.”[14] Bobby was always with Ivor at his weekend redoubt Redroofs, and despite his lack of musical talent, Ivor featured him as William Fayre and Bill in PERCHANCE TO DREAM (1945) and as Vanescu in KING’S RHAPSODY (1949).

Novello and Mary Ellis in “Glamorous Nights”.

Apart from a steady series of successful West End comedies (I LIVED WITH YOU; PARTY; FLIES IN THE SUN; FRESH FIELDS; PROSCENIUM; THE SUNSHINE SISTERS; MURDER IN MAYFAIR) Ivor Novello turned at last to operetta which was to prove his crowning achievement. GLAMOROUS NIGHT (2 May 1935, Theater Royal, Drury Lane, 243) was “part opera, part melodrama, part operetta, part musical comedy.”[15] Novello devised and wrote the play, composed its melodies, but left the craft of lyrics to Christopher Hassall[16]. Henceforth a “Novello show” meant that Novello himself played a non-singing hero[17], who loved, lost or won many ladies, or who was loved, was lost or was won by many ladies; they did all the singing, amidst ravishingly spectacular sets, a preposterous plot, adorned with sentimental melodies. Note that no male rival could be allowed to sing too well, or dance or act with greater charm than the hero Ivor. Such constraints tailored these Novello shows to the talents of their star, so that without Ivor they were seldom produced professionally afterwards, unless radically revised. No Novello musical was ever produced outside the English-speaking world, and in America only GLAMOROUS NIGHT and THE DANCING YEARS received one week outdoor premieres at the St. Louis Municipal Opera in 1936 and 1947, respectively. A contemporary critic in London’s Daily Mail offers this précis of the plot:

“Anthony Allan [Ivor Novello] is the young inventor of a new TV process who is given £500 by Lord Radio…to keep quiet. The scene shifts to Krasnia, where backwards English is spoken—as we can tell from the notice, ON GNIKOMS, in its opera house. King Stefan of Krasnia loves Melitza, a Gypsy prima donna, whom we see and hear at a grand gala performance, ending in an attempt on her life. Here is Anthony’s chance. He disarms the would-be assassin and is invited to the gypsy’s boudoir. Then he has to return to his ship for the duration of the cruise, plus her checque for £1000. She follows. Gay scenes aboard ship end in a spectacular wreck. Our hero and his prima donna reach the shore where they are married gypsy fashion. But her country is in danger, and to save it she has to agree to become queen. He returns to England and witnesses her coronation by means of the TV he has invented.” This account neglects to include the irrelevant black stowaway Cleo Wellington (played by the timeless Elisabeth Welch) and her two songs, the obligatory show-within-a-show, or the scene in which Anthony prevents the King’s execution by shooting the wicked Baron Lydyeff dead.

Although GLAMOROUS NIGHT easily have run for two years, the Drury Lane management forced it to close for a prior booking of its annual Christmas pantomime (JACK AND THE BEANSTALK) in December 1935. Novello’s absurd plot echoed in eerily prescient fashion the British monarch Edward VIII’s abdication of the throne in January 1936 for Wallis Simpson, the American divorcée he loved. The choice of duty vs. love, royalty vs. commoner, or commoner becoming king or queen, was a popular, traditional story for operettas, yet here was a true life story imitating operetta! Women flocked to Novello’s Drury Lane operettas for their sentiment and spectacle, and although overtly heterosexual in their story-line, there was scant audience appeal for the heterosexual male. Note also Novello’s oft-overlooked achievement was his devising of a stage spectacle that rivaled if not surpassed the visual extravagance of film musicals, now that the technical problems of “talkies” had been overcome.

Autograph card, Ivor Novello.

Inexplicably, the Drury Lane management at first declined to produce CARELESS RAPTURE, the new operetta Novello offered them. Much to management’s chagrin and Novello’s delight, JACK AND THE BEANSTALK earned no profits, perhaps due to King Edward’s abdication in January, then Robert Stolz and Robert Gilbert’s RISE AND SHINE collapsed after 44 performances. Suddenly Novello and CARELESS RAPTURE (11 September 1936, 296 performances) were offered the Drury Lane on favorable terms for immediate production. This new “Novello show” adhered to formula with its tale of penniless bastard Michael (Novello) and his wicked brother Sir Rodney Alderney, both in rival pursuit of musical comedy star Penelope Lee (Dorothy Dickson). This tale of deceit, misunderstandings and betrayal took its protagonists from a London beauty parlour, to singing lessons, rehearsals of Penelope’s operetta ‘The Rose Girl,’ a Merry-Go-Round on Hampstead Heath, to China, an earthquake, refuge in the mountains, and capture by Chinese brigands. Novello even disguised himself as a Chinese prince. CARELESS RAPTURE may not have produced any enduring musical hits, but Novello attempted a little ill-advised singing and dancing, and his audiences were thrilled by the romance and the spectacle.

Under the entrepreneurial management of young Tom Arnold, the third and least successful of Novello’s annual Drury Lane musical spectacles was CREST OF THE WAVE (1 September 1937, 203 performances). Novello created for himself simultaneous roles as the poor hero, Don Gantry, Duke of Cheviot, and the villain, Otto Fresch, architect of the year’s requisite theatrical disaster, a train crash! The girl interest this time was Dorothy Dickson as Honey Wortle, a cockney film extra with musical talents. From Gantry Castle, to London film studios of “Fair Maid of France,” the S.S. Queen Anne, the Café del Gracias Señoras in Rio de Janeiro (where our hero Don Gantry is assinated for the Act 1 finale!), then Hollywood, CREST OF THE WAVE offered audiences spectacle but little else. Only one song, “Rose of England,” dimly evocative of Novello’s own “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” endured beyond the run of the show. Perhaps, some wondered, the “Novello show” formula had exhausted Ivor’s inspiration?

Seeking a new challenge beyond that of musical hero, Novello next attempted the title role in Shakespeare’s HENRY V, under the direction of Lewis Casson, a most-experienced and respected interpreter of the bard. But Drury Lane audiences proved unwilling to revise their expectations of Novello from romantic hero to Shakespearean actor and military hero. Despite excellent personal reviews for Novello, the English theatre-going public were wary of the threat of war from the Munich Crisis of 1938, and the production failed. While touring with CREST OF THE WAVE, Novello discovered the inspiration what would prove his most enduring work, THE DANCING YEARS (23 March 1939 Drury Lane, 187; 14 March 1942, Adelphi, 969). “The idea for the piece was apparently suggested to him by the discovery that a friend, trying to buy gramophone records in Vienna, had found that all records by Jewish composers had been suppressed. Novello imagined what his own position under such circumstances might be, and from that beginning, evolved the character of the composer, Rudi Kleber, for himself and THE DANCING YEARS for Drury Lane.”[18] Novello shrewdly gauged English public opinion and his own audience’s expectations, and fused contemporary world politics with operetta to dazzling effect.

Novello and Roma Beaumont in “The Dancing Years”.

Novello played Rudi Kleber, a talented Jewish composer of operettas, whose work is embraced by Viennese prima donna Maria Ziegler (Mary Ellis). Their collaboration evolves into romance, but he is unable to marry her because of a childhood promise to wed Grete. Although Maria is pregnant with their child, she breaks with Rudi to wed an older, wealthy suitor, Prince Metterling. Years later after Rudi’s and Grete’s international success in musical comedy is established, Maria and Rudi meet by chance and arrange a secret rendezvous. Maria arrives with Rudi’s son Otto, but Mari and Rudi are reconciled they must live their lives apart, and she tells him his music “has made the whole world dance.” THE DANCING YEARS introduced three of Novello’s most enduring romantic ballads, “Waltz of My Heart”, “My Dearest Dear, “ and “I Can Give You the Starlight.”

Much to the consternation of the Drury Lane management, Novello’s manuscript opened with a prologue in which Rudi, “now an old man, is condemned to death by the Nazis for his complicity in the escape of Jews from Austria… But Ivor stood his ground and in the version presented at Drury Lane the scene came at the end; but Maria, through the influence of her husband, obtains a reprieve, and in the final moments, assures Rudi that her son by him is free of any taint of Nazism.”[19] This romantic tragedy resonated powerfully for London pre-war audiences, but the 188-performance run was cut short when all West End theatres were closed on 1 September 1939 at the outbreak of war. THE DANCING YEARS re-opened a year later for a national tour of the provinces with Novello starred. Its unprecedented success led to its return to London 14 March 1942 to the Adelphi for an additional 969 performances. Curiously, later revivals and amateur productions have excised the prologue/epilogue, de-fanging the story contrary to the author’s original intent.

Novello as Rudi Kleber, being arrested by the Nazis.

Despite the rigors of starring in THE DANCING YEARS on tour, Novello tailored yet another “Novello show,” ARC DE TRIOMPHE (9 November 1943, Phoenix, 222) as a vehicle for Mary Ellis, sans Novello himself. Mary Ellis was Marie Forêt, a French opera singer, whose career travails and romantic misfortunes culminate in an opera-within-the-play about Joan of Arc, in which she sings her aria “France Will Rise Again.” Far from Novello’s best work, its moderate success was curtailed by enemy bombs in the summer of 1944, and a general feeling that a Novello show without Novello was somehow lacking.

Ivor’s personal success in THE DANCING YEARS may have mis-led him into thinking his celebrity entitled him to privileges denied others. Novello became annoyed when his application for exemption from wartime petrol restrictions was turned down in December 1942. Grace Walton, a long-time Novello fan known to her employer, Electrical and General Trusts Ltd., as Dora Constable, secured the use of a private company car which enabled Novello to travel to and from his country estate Redroofs on weekends. By the time the ruse was later exposed, Novello was sentenced to 8 weeks’ inprisonment at Wormwood Scrubs, reduced by half. Super-stardom clouds judgement and corrupts the mind, and some friends and later biographers have speculated the resulting public relations debacle and jail-time led to a decline in his health and his premature death. Although he returned to the cast of THE DANCING YEARS on 20 June 1944 to delirious acclaim, the hero in Novello was no longer invincible as before.

With the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane still conscripted for military use, Novello and Arnold booked the next “Novello show,” PERCHANCE TO DREAM into the Hippodrome (21 April 1945, 1022 performances), located atop Leicester Square. Novello’s dramatic conceit was a musical triptych with three successive generations occupying the same country home Huntersmoon, in the 1820s (Regency era), 1890s (Victorian era) and 1930s (near present). Novello played first a highwayman Sir Graham Rodney who dies, then music teacher Valentine Fayre, and finally their descendant Bay, who happily weds the beautiful quarry Melody (Roma Beaumont). In Acts 1 and 2 respectively, Miss Beaumont was Rodney’s quarry Melinda, then Fayre’s true love Melanie, who commits suicide when she discovers Fayre’s wife is pregnant. For wartime audiences, PERCHANCE TO DREAM boasted a welcome happy ending after two acts of thwarted romance, Novello’s best score aside from THE DANCING YEARS, and a dashing Ivor in not one, but three roles. With a nod to the wartime constraints of a smaller stage and less backstage manpower, there was no onstage disaster spectacle, no “show-within-a-show,” but instead a somewhat coherent narrative. The hit song “We’ll Gather Lilacs” struck a sentimental chord:

“We’ll gather lilacs in the spring again

And walk together down an English lane

Until our hearts have learned to sing again

When you are home once more.

And in the evening by the firelight’s glow

I hold you close and never let you go

Your eyes will tell me all I want to know

When you are home once more.”

Equally enduring was the sweeping waltz, “Love Is My Reason for Living.” PERCHANCE TO DREAM could have run forever, but after two and a half years, Novello and Co. took it to South Africa, then back for a tour of the British Isles.

During that tour, Novello composed what would be his last triumph, KING’S RHAPSODY (15 September 1951, Palace, 881), a conscious return to operetta’s favorite Ruritania setting and its traditional contretemps among the royals. Novello penned his most coherent libretto yet, with himself accurately cast as the aging (he was 56) Prince Nikki of Murania. Summoned home from Paris and the arms of his mistress Marta (Phyllis Dare) upon the death of his father, Nikki accedes to the throne, and with the machinations of his mother Queen Elena (Zena Dare), he weds Princess Cristiane (Vanessa Lee) of neighboring Norseland. Along the way there is a peasant rebellion, a betrothal ball, and an endless Muranian Rhapsody ballet; Nikki mistakes Cristiane for a maid and seduces her. Cristiane bears Nikki a son, and she becomes more popular as Queen than he as King. Wicked Prime Minister Vanescu (Robert Andrews!) kidnaps the infant son, and blackmails Nikki into abdicating the crown for the safe return of his son. Unseen by all, Nikki watches the coronation of his son, then retrieves a white rose left for him as the curtain falls. One of Novello’s stronger scores, it is best remembered for Vanessa Lee’s soaring ballad “Someday My Heart Will Awake.”

Novello eschewed the requisite “show-within-a-show” and disaster spectacle of previous Novello shows, but delivered a sentimental tragedy with sweeping melody which delighted his public, and drew much grudging critical respect. KING’S RHAPSODY was a determinedly British rebuke to the newly dominant form of the American musical play, whose OKLAHOMA!, ANNIE GET YOUR GUN and BRIGADOON had swept the West End.

Not content to rest on these laurels, Ivor Novello wrote his own musical play, really a musical comedy as a vehicle for that enduringly popular star Cicely Courtneidge. GAY’S THE WORD was not at all a modern musical comedy, as it was a return to the ramshackle musical farces of the 1930’s West End. Its title, unproduceable with today’s meaning of the word, was a tribute to the “vitality” and “high spirits” of its well-known star. Miss Courtneidge played Gay Daventry, star of a new Novello-style operetta flop, who decides to open an acting school in suburban Folkstone. Novello deployed several devices his audiences would recognize, a self-parody opening “Ruritania” (Guards on Parade), and two “show(s)-within-a-show.” Otherwise, the backstage contrivances of the plot and its smugglers on the loose, afforded a revue-like structure to showcase its star. With Courtneidge’s husband Jack Hulbert on board as director, and skilled revue-writer Alan Melville as lyricist, Novello found his a-typical GAY’S THE WORD to be a major West End hit, with a 15-month run and extanded national tour.

Eighteen months into the capacity run of KING’S RHAPSODY and a mere month after the opening of GAY’S THE WORD, Ivor Novello collapsed and died at his home on 6 March 1951 following a performance of KING’S RHAPSODY. Producer Tom Arnold had shared a post-performance supper at the actor’s flat above the Aldwych Theatre, then left. Robert Andrews, who shared the flat with Ivor[20], returned and found him unconscious, but Novello died before help arrived. Although profoundly beloved by the English theatre-going public, Novello’s reputation began to fade soon after his death. An inferior film adaptation of KING’S RHAPSODY (1955) directed by Herbert Wilcox, starring Errol Flynn as King Richard (formerly Nikki), Anna Neagle as mistress Marta, and Patrice Wymore as Cristaine, did nothing to propagate Novello’s reputation. The Novello operettas became the exclusive domain of regional amateur light opera societies in the 1950s and 1960s, before fading altogether from view. A brief west End revival of THE DANCING YEARS in 1968 under the auspices of Tom Arnold, and major regional productions of PERCHANCE TO DREAM and KING’S RHAPSODY have offered little reprieve to Novello’s fame. Given the international success of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s romantic operetta THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, perhaps the time is right to re-examine Novello’s finest music and the musicals which begat them.

Conversely, Noël Coward, who survived Novello by 22 years, lived to see himself knighted, transformed into an international cabaret star, sometime film character actor. His plays were rediscovered in the 1960s and 1970s, and through the efforts of Sheridan Morley, Graham Payn, Cole Lesley, Barry Day among others, have assumed the status of modern classics. At a charity memorial performance honoring Ivor Novello at the London Coliseum on 7 October 1951, Noël Coward wrote and spoke the following, which eloquently expressed his respect, esteem and friendship for Novello, but also offers uncanny insight into just how he hoped he too would someday be remembered:

“Dear Ivor: Here we are, your world of friends

The theatre world, the world you so adored,

Each of us in our hearts remembering

Some aspect of you, something we can hold

Untarnished and inviolate until

For us as well the final curtain falls.

For some of us your talent, charm and fame

The outward trappings of your brilliant life,

Were all we knew of you and all we’ll miss.

But others, like myself, who loved you well

And knew you intimately, here we stand

Strangely bewildered, lost, incredulous

That you, so suddenly, should go away.

Those of us here to-night who have performed

And sung your melodies and said your words

Professionally, carefully rehearsed,

Have felt, I know, behind their actor’s pride

In acting, a deep, personal dismay —

A heartache underlying every phrase.

The heartache will eventually fade,

he passing years will be considerate,

But one thing Time will never quite erase

Is memory. None of us will forget,

However long we live, your quality;

Your warm and loving heart; your prodigal,

Unfailing generosity, and all

Your numberless, uncounted kindnesses.

I hope, my dear, that after a short while

There’ll be no further sorrow, no more tears.

We must remember only all the years

Of fun and laughter that we owe to you.

Mournfulness would be sorry recompense

For all the joy you gave us, all the jokes

Yoru lovely sense of humour let us share.

Gay is the word for all our memories,

Gay they shall be for ever and a day,

And there’s no greater tribute we can pay.” [21]

Bibliography:

Clum, John. Something for the Boys: Musical Theater and Gay Culture. New York: St. Martins’ Press, 1999.

Coward, Noël: The Complete Lyrics. Edited and annotated by Barry Day. Woodstock and New York: Overlook Press, 1999.

Coward, Noël. Future Indefinite. A Second Volume of Autobiography. London: William Heinemann, Ltd., 1954.

Coward, Noël. Present Indicative. London: William Heinemann, Ltd., 1937.

Fisher, Clive. Noël Coward. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1992.

Harding, James. Ivor Novello. London: W H Allen, 1987.

Hoare, Philip. Noël Coward. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Huggett, Richard. Binkie Beamount: Eminence Grise of the West End Theatre 1933-1973. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989.

Koestenbaum, Wayne. The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire. New York: DaCapo Press, 2001.

Lesley, Cole, Graham Payn and Sheridan Morley. Noël Coward and Friends. New York: William Morrow, 1979.

MacQueen-Pope, Walter James. Ivor: The Story of an Achievement: A Biography of Ivor Novello. London, W. H. Allen, 1951.

Morella, Joseph, and George Mazzei. Genius & Lust: The Creative and Sexual Lives of Cole Porter and Noël Coward. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1995.

Morley, Sheridan. A Talent to Amuse: A Biography of Noël Coward. London: William Heinemann, 1969.

Noble, Peter. Ivor Novello: Man of the Theatre. London: Falcon Press, 1951.

Payn, Graham, with Barry Day. My Life with Noël Coward. New York and London: Applause Books, 1994.

Rose, Richard. Perchance to Dream. The World of Ivor Novello. London: Leslie Frewin, 1974.

Wildeblood, Peter. Against the Law. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1955.

Wilson, Sandy. Ivor Novello. London: Michael Joseph, 1975.

Select discography on compact disc:

Noël Coward: His HMV Recordings 1928-1953. EMI 0777 7 80580 2 1. (4 compact disc boxed set issued 1992, Coward vocals)

Noël Coward: The Great Shows EMI 7243 5 21808 2 0

Noël Coward – The Revues EMI 7243 5 20729 2 7

Ivor Novello: The Classic Shows. EMI CDP 7943682

[1]Coward, Noë; Coward, The Complete Lyrics, Edietd and annotated by Barry Day. Woodstock and New York: The Overlook Press, 1998, p. 114.

[2]The MGM film version dispensed with much of Coward’s plot, and all but 6 Coward songs, many of whose lyrics were altered by Gus Kahn.

[3]Coward, Complete Lyrics, p. 195.

[4]Coward, Complete Lyrics, p. 197.

[5]Thornton, Michael, “Mad About the Boy,” Daily Mail, 14 November 2005, pp. 34-5.

[6]Coward, Complete Lyrics, p. 261.

[7]Coward, Complete Lyrics, p. 295.

[8]Many observers thought Sir Hugo Laytmer resembled Coward’s good friend, author and playwright Somerset Maugham.

[9]Huggett, Richard. Binkie Beamount: Eminence Grise of the West End Theatre 1933-1973. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989, p. 429-32.

[10]Wildeblood, Peter. Against the Law. London, 1955.

[11]Hoare, Philip, Noël Coward: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 122.

[12]Also known as “’Till the Boys Come Home,” published by Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew, Ltd. in London, and Leo Feist, Inc. in New York.

[13]The Queen, June 1924, quoted in Ivor, by Sandy Wilson (Michael Joseph Ltd., London, 1975), p. 120.

[14]Agate, James, London Sunday Times, September 1934.

[15]Wilson, Sandy. Ivor. p. 188.

[16]Seldom if ever in the musical theatre has the composer been the librettist without writing his own lyrics. Since Hassall was unavailable at the time, Novello wrote his own lyrics for PERCHANCE TO DREAM.

[17]In stark contrast to operetta convention and the works of Franz Lehàr and Richard Tauber.

[18]Gänzl, Kurt. The British Musical Theatre, Volume II, 1915-1984. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, p. 498.

[19]Wilson, Sandy. Ivor, p. 226.

[20]The Star, 6 March 1951, “Ivor Novello dies 4 hours after show,” p. 2. Also quoted in Wilson, Sandy: Ivor, p.264.

[21]Coward, Noël. Quoted in Theatrical Companion to Coward, by Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson. London: Rockliff, 1957, p. 30.

wunderbar – was für ein schöner und lesenswerter artikel. und die details sind nicht nur für fans der beiden (wie ich) bereichernd – danke gh

Ivor Novello was born in Cardiff to Welsh parents and was NOT English.

This is a scrupulously compiled tribute. Well done! For younger generations would a compact, two-paragraph version be in order to whet green appetites?

<I have read some not so endearing quotes from Coward about dear Ivor: