Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 January, 2001

Franz von Suppé followed up his first great success with a full-length Operette, Fatinitza, with a second, three years later. Boccaccio‘s neatly constructed text by F Zell and Richard Genée was allegedly borrowed from an unspecified theatre piece by Bayard, de Leuwen and de Beauplan, but, whether it was or not, it certainly helped itself to some plot motifs from one of the chapters of the real Boccaccio’s famous work, the collection of often ribald tales known as The Decameron. It had, otherwise, little enough to do with the historical Italian author, Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), for whom it was named — a trend which would long persist in the musical theatre — but at least his name supplied a nicely recognizable and slightly suggestive title. The show premiered at the Carltheater, Vienna, on 1 February 1879.

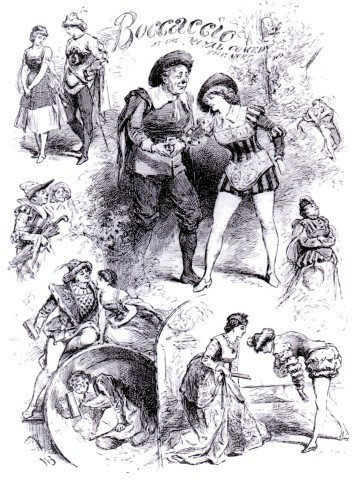

Poster for a “Boccaccio” production in London, 1882.

Giovanni Boccaccio (Antonie Link) is a poet and novelist who takes the plots for his tales of duped husbands and faithless women from life and from his experience of it. This excuse of ‘research’ is, of course, an excellent one for making off with any available 14th-century Florentine wives (other people’s) he can. The latest of these is Beatrice (Frln Bisca), wife of Scalza (Hildebrandt), the barber. However, Beatrice is put in the shade and Boccaccio all swept away when he sees the unmarried Fiametta (Rosa Streitmann), the foster-daughter of the grocer Lambertuccio (Karl Blasel) and his wife, Peronella (Therese Schäfer). What he does not now is that Fiametta is no groicery miss, but the farmed-out daughter of the Duke of Tuscany. Pietro, Prince of Palermo (Franz Tewele), a royal with an itch to be an author on Boccaccio’s lines and principles, comes to Florence incognito in search of some `real life’, and the writer and his friends take him on a jaunt with Isabella (Regine Klein), the wife of the cooper, Lotteringhi (Franz Eppich), which ends up with the Prince hidden in a barrel to escape the jealous husband. Boccaccio himself, caught kissing Fiametta, persuades the foolish grocer that his olive tree has hallucinatory powers. Finally Fiametta is summoned home, to marry a royal husband.. Fortunately, the royal in question is none other than Pietro, who is willing and able to hand her over to her slightly reformed Boccaccio. The final act, set in the Tuscan court, justified the poet’s presence by positing that he had been hired to write and stage an entertainment for the royal betrothal. That entertainment, when given, took the form of a moral commedia dell’arte piece in which the principal comedians took part: Blasel as Pantalone, Eppich as Brighella, Hildebrandt as Narcissino, with the young Carl Streitmann as Arlecchino and Frln Poth as Colombina.

Suppé’s score was a worthy successor to that for Fatinitza, featuring such winning romantic numbers as Boccaccio and Fiametta’s waltzing third-act `Florenz hat schöne Frauen’, their second-act duo `Nur ein Wort’ and the serenade `Ein Stern zu sein’, alongside a tunefully winsome yet amusing trio (`Wonnevolle Kunde, neu belebend’) in which Fiametta, Isabella and Peronella read the love/sex-notes wrapped around stones and hurled at their feet by Boccaccio, Pietro and Leonetto, the march septet (`Ihr Toren, ihr wollt hassen mich’) leading up to the conclusion of the show, and some substantial and substantially written finales. The comical highlight of the piece was the song of the cooper, banging away at his barrel-making to drown out his wife’s nagging (`Tagtäglich zankt mein Weib’), whilst the other cuckolded husbands also had their moments of fun, as in the opening act when Scalza and his friends serenade his wife to the plunking of his umbrella (`Holde Schöne’). The quality of the score for the second and, particularly, the third act — an act often used in Operette simply to briefly tie up the ends — helped to give Boccaccio an additional shapely strength.

Boccaccio was a splendid success at the Carltheater. It was played 32 times en suite before Antonie Link went into retirement and left her rôle to Regine Klein, and no fewer than 80 times by the end of the year.

The 115th performance was played on 3 October 1881, by which time Boccaccio had become established as an international hit of some scope, but the Carltheater then curiously let the piece drop from its repertoire and thereafter it appeared there only intermittently (matinées in 1906 and 1922, 16 October 1923 w Erika Wagner and Christl Mardayn). The other Viennese theatres, however, snapped the show up and Boccaccio was mounted at the Theater an der Wien in 1882 (16 September) with Karoline Finaly in the title rôle, Alexander Girardi as Pietro, Carl Adolf Friese (Scalza), Josef Joseffy (Lotteringhi), Felix Schweighofer (Lambertuccio), Marie-Therese Massa (Beatrice) and with Fr Schäfer and Frln Streitmann in their original rôles. A new production was staged there in 1885, Julie Kronthal was Boccaccio in 1891 and the piece reappeared in 1901 and 1907. It also appeared at the Venedig in Wien summer theatre in 1899 (5 July), entered the Volksoper in 1908 (10 November), played at the Johann Strauss-Theater in 1911, and Paula Zulka starred as Boccaccio at the Raimundtheater in 1915 (2 January).

Marie Geistinger as Boccaccio, in Vienna.

Subsequent to this merry run of performances, Boccaccio began to suffer under the hands of the `improvers’ and, for a show which won such success on its initial productions and has ever since been quoted as one of the classic comic operas of its period, it has since been chopped-up, deconstructed and musically maltreated more often that would have been expected. A version which aimed to operaticize a show which was very far from being an opera, replacing dialogue with recitative and tacking in extraneous bits of Suppé music, was done by Artur Bodanzky and, after being seen at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in 1931, was staged at the Vienna Staatsoper, in each case with Maria Jeritza as Boccaccio. Another heavily remade version (ad Adolf Rott, Friedrich Shreyvogel, mus ad Anton Paulik, Rudolf Kattnigg) also gained currency and royalties for its remakers and publishers for a while, and the trend has continued in Vienna to the present day, where the most recent Volksoper production, whilst eschewing recitative, turned what remained of the piece (ad Torsten Fischer) from a comic opera into shapeless black-and-scowling melodrama, simply altering or cutting any portion of text or score which did not fit into the unimaginative 1960s-style `concept’ imposed by its director/adapter. Amongst the other unnecessary (although not unprecedented) alterations made, Boje Skovhus, who played the mangled rôle of Boccaccio, was not a mezzo-soprano.

A typical post-WW2 LP version of “Boccaccio” from the Voilksoper Wien, conducted by Anton Paulik.

Boccaccio followed up its original success in Vienna with another in Germany and a huge one in Budapest (ad Lajos Evva). Produced at the Népszinház with Lujza Blaha in the title rôle, and Elek Solymossy (Pietro), Mariska Komáromi (Fiametta), János Kápolnai (Lotteringhi), Zsófi Csatay (Isabella) and Emilia Sziklai (Beatrice) amongst the cast, it raced to its 50th performance (30 October 1880), was revived in 1882 (11 October), 1883 (11 September), 1887 (14 January) and 1889 (2 May w Aranka Hegyi), passed its hundredth performance on 9 May 1890, and was reprised again on 1 October 1904, running up a record which only Les Cloches de Corneville, Der Zigeunerbaron and Rip van Winkle amongst early musical plays equalled in the Hungarian capital. It found its way also into other houses, and in 1922 Juci Lábass starred in a revival at the Városi Színház.

Following its first German production, in Frankfurt, the original version was quickly seen in Prague (23 March 1880), Nuremberg (4 April 1880), Berlin and at New York’s Thalia Theater where Mathilde Cottrelly donned the poet’s breeches. The first English version, which had premièred in Philadelpha in early April, arrived on Broadway only weeks after this, when Jeannie Winston appeared as Boccaccio at the Union Square Theater with Mahn’s English Opera Company. W A Morgan (Pietro), A H Bell (Lambertuccio), Marie Somerville (Isabella), Hattie Richardson (Beatrice) and Fred Dixon (Lotteringhi) supported. This staunchly touring company brought the show back to New York the following year (Niblo’s Garden 17 November 1881), by which time the Boston Ideal Company had another version, entitled The Prince of Palermo, or the Students of Florence (ad William Dexter Smith, Boston Theatre 10 May 1880), prominently displayed in their repertoire, Emilie Melville had appeared with great success at San Francisco’s Bush Theater (7 June 1880) and on the road in an Oscar Weil/G Heinrichs adaptation, and Boccaccio had become a nation-wide favourite. In 1888 (Wallack’s Theater 11 March) the piece got a high-class revival from the De Wolf Hopper company with the star as Lambertuccio to the Boccaccio of Marion Manola, the Scalza of Jeff de Angelis, the Lotteringhi of Digby Bell and the Peronella of Laura Joyce Bell. Broadway saw Boccaccio again (ad H B Smith) when Fritzi Scheff took on the rôle at the Broadway Theatre in 1905 (27 February) before Bodanzky and the Metropolitan Opera brought their operaticky version to the New York stage. Another heavily rewritten Boccaccio was seen in 1932 with filmstar-to-be Allan Jones featured in the title-rôle.

It was 1882 before London saw its first Boccaccio (ad H B Farnie, Robert Reece) at the Comedy Theatre with Violet Cameron starred in the title-rôle alongside Alice Burville (Fiametta), James G Taylor (Pietro), Lionel Brough (Lambertuccio), Will S Rising (Leonetto), Louis Kelleher (Lotteringhi), Kate Munroe (Isabella) and Rosa Carlingford (Peronella). It had, of course, been previously pillaged by the pasticcio-makers of London, and the Alhambra production of Babil and Bijou, which was running concurrently with Alexander Henderson’s Boccaccio production, was using no less than five numbers lifted from Suppé’s score. This preview didn’t seem to harm the show’s prospects, for the Comedy Theatre production ran for an excellent 129 straight performances before the theatre was shut for repairs, and it returned thereafter to carry on for nearly another month until the new Rip van Winkle was ready. It was brought back to the same house in 1885 (30 May) when Miss Cameron repeated her rôle opposite the young Marie Tempest (Fiametta) and Arthur Roberts (Lambertuccio) for a brief season.

Australia welcomed Emilie Melville and her version `as sung more than 300 times by her in America’ with Armes Beaumont (Pietro), Annie Leaf (Fiametta) and Mrs J H Fox (Isabella) in support, and this was followed into town by the Reece and Farnie version, played by Alfred Dunning’s London Comic Opera Company with Kate Chard, and advertised as being `in no way similar’ to the American Boccaccio! Australia thereafter saw the piece regularly for a number of years, played in various comic opera companies’ repertoires.

As was so often the case, Boccace (ad Henri Chivot, Alfred Duru) reached Brussels in its French version (Galeries Saint-Hubert 3 February 1882) before moving into Paris. In the Folies-Dramatiques production Mlle Montbazon starred in the title-rôle to the Orlando (ex-Pietro) of Desiré, with Luco, Lepers and Maugé in the other male rôles and Berthe Thibault as Béatrice (ex-Fiametta) as the show added one more success to its international list. It was revived in Paris in 1896 with Anna Tariol-Baugé, at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique in 1914 with Jane Alstein and again in 1921 with Marthe Chenal starred.

Boccaccio has continued to win revivals, if all too frequently in botched versions, in both opera and operetta houses in Europe, as well as being the subject of a justifiable quota of recordings.

A film version which was produced in 1936 with Willi Fritsch playing Boccaccio seems, on the evidence of that casting, as if it probably didn’t stick very close to the original. A 1940 Italian one junked the book but used some of the music and at least had a female lead.

An issue of the “Filmillustrierte” with a cover dedicated to the “Boccaccio” film starring Willy Fritsch.

The title was re-used for an American musical (Richard Peaslee/Kenneth Cavander) based on tales from The Decameron and played for seven performances at the Edison Theater in 1975 (24 November), whilst a number of other musical shows have been announced over the years as being `based on a tale by Boccaccio’. At some periods, such an announcement would seem to have been nothing but a way of adding the respectability of a dead, foreign, classic author to a libretto which got closer to other parts of the body than to the knuckle. Others merely used a pale and proper outline of Boccacio’s tales.. The poet is credited, amongst others, as source on the highly successful French comic opera Le Coeur et la main (Lecocq/Charles Nuitter, Alexandre Beaumont, Théâtre des Nouveautés 19 October 1882), Lecocq’s little Gandolfo, in tandem with Shakespeare as the bases of the libretto to Audran’s Gillette de Narbonne, on a Malbruck, written by Angelo Nessi and composed by Ruggiero Leoncavallo (Teatro Nazionale, Rome 19 January 1910), and Harry and Robert Smith’s flop musical The Masked Model (National Theatre, Washington 7 February 1916, which was later revamped as Molly O (Cort Theater 20 May 1916).

In France, a fictional opéra-bouffe called Le Roi Candaule founded on Boccaccio’s tale of the same name, was used as the subject matter for Meilhac and Halévy’s comedy Le Roi Candaule which dealt with the high-jinks that go on in a theatre when husbands take each other’s wives out to see a naughty show and, of course, end up in the same box.

Germany: Viktoria Theater, Frankfurt 13 March 1879, Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater 20 September 1879; Hungary: Népszinház 1 October 1879; USA: Thalia Theater 23 April 1880, Chestnut Street Theater, Philadelphia (Eng) 5 April 1880, Union Square Theater (Eng) 15 May 1880; France: Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques 29 March 1882; UK: Comedy Theatre 22 April 1882; Australia: Opera House, Melbourne 2 September 1882;

Films: Herbert Maisch 1936, (It) 1940

Recordings: complete (EMI), selections (Philips, Eurodisc etc), selection in Hungarian (Qualiton, part record)