Thomas Bierling

Operetta Research Center

2 November, 2014

Composing a brand-new operetta today is a daring endeavor. On the one hand, larger audiences are drawn to dramatic musicals and appear to regard operettas as little more than dusty cultural artifacts from their grandmother’s era. On the other hand, it is difficult to gain ground among dyed-in-the-wool operetta lovers, what with the best of Offenbach, Strauss, Lehár et al in heavy rotation.

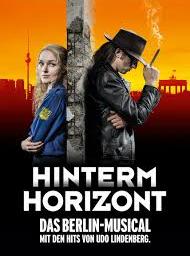

Poster for the East/West Berlin Wall musical “Hinterm Horizont.”

In light of the fact that musicals in Germany today focus largely on dramatic stories ― examples include Phantom of the Opera and the Berlin-Wall show Hinterm Horizont ― authors who want to address satirical and humorous topics are almost inevitably compelled to turn to the art form of the operetta. After all, in its heyday, the medium was the finest vehicle for cabaret-like comedy and off-kilter satire.

For their operetta Stéphanie, Thomas Bierling (music) and Konstantin Schmidt (libretto) have adapted historic material which is inherently comedic in nature, since it involves worlds colliding and characters who could not be any more different. In 1806 Napoléon Bonaparte wed off his adopted daughter Stéphanie de Beauharnais in a strategic marriage to Karlsruhe’s crown prince, Karl von Baden. The 16-year-old from the modern imperial court of Paris was thus matched with a 19-year-old from a small provincial principality on the Upper Rhine. To complicate matters, the well-established nobility at the Karlsruhe court of Baden loathed the conqueror Napoléon and were not welcoming to his daughter, and their sentiments could be clearly felt at the palace.

Stéphanie, however, had the things she needed to stir things up at the Baden court: she was young, pretty and prissy. By contrast, her new groom was striking in his shyness, indecisiveness and desire to avoid conflict. And the crowning blow was that they were expected to produce an heir – an obligation which may well have brought forth Kaspar Hauser, the mysterious foundling. It took many years and multiple rounds of harsh words from Napoléon before Stéphanie and Karl finally found their way as a couple.

Stéphanie de Beauharnais was no Empress Sissi of Austria, and Karlsruhe was no cosmopolitan metropolis. But the story has everything that makes for a good tale: love, intrigue, jealousy.

Painting of Stéphanie de Beauharnais by François Pascal Simon, Baron Gérard (1806).

And in terms of the political machinations, the court of Baden could certainly hold its own against Paris and Vienna; it too was full of conspiracies, self-indulgence, avarice and recklessness.

Stéphanie ties into the traditional conventions of the operetta with its satirical content and its score for orchestra and classical voices. The plot and dialogues, however, are influenced by the current style in terms of dramatic tension and comedy. This makes Stéphanie a new operetta of the sort that should be written today.

Can this approach work, though? Can a form of theater that is considered classic be opened up to modern concepts and in turn to new audiences?

On behalf of the authors, Torsten Stoll staged a ‘proof of concept’ of sorts, a 45-minute review in an arrangement for four vocalists in six roles with piano accompaniment.

Its world premiere was at the Karlsruhe Museum Night in 2014. The crowds it drew included people of all ages, and they were by no means a typical operetta audience. In three performances for nearly 600 listeners, it became clear that Stéphanie was an idea whose time had come. Even audience members who were less familiar with operettas found the review entertaining and amusing. Aficionados of classical voices praised the music, and the reviews in the press were positive.

The message for the authors is clear: Stéphanie is ready to be presented in full. The search for the proper stage has begun.

Scene from the new operetta “Stéphanie.”