Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

28 January, 2015

The 27th of January 2015 was a memorial day, not only in Germany, but there especially. 70 years ago the Russian army liberated the surviving prisoners of concentration camp Auschwitz. And the German president said in a moving speech: “There is no German identity without Auschwitz!” On that special day, Barrie Kosky presented a late-night show of “Yiddish Operetta Songs” at the Komische Oper Berlin, with Alma Sadé and Helene Schneiderman. Title of their program: “Farges Mikh Nit.”

Barrie Kosky and his two soloists, Alma Sadé (l.) and Helene Schneiderman. (Photo: Privat)

But don’t get the wrong idea. This was not (decidedly not) a Holocaust Memorial concert. Far from it. Kosky’s aim was to offer Berlin audiences something new to discover: Yiddish Operetta. All of this as part of the current operetta festival that wants to show – with a vengeance – that there is more to operetta than the eternal standards Fledermaus and Lustige Witwe.

While the upcoming premiere of Oscar Straus’ Eine Frau, die weiß was sie will (1932) can at least boast four famous songs that operetta aficionados will know, by heart, and while the other “rarities” – Abraham’s Ball im Savoy (1932) and Dostal’s Clivia (1933!) – have become permanently sold-out hit productions, Yiddish Operetta is something even the most enlightened will probably not know much about.

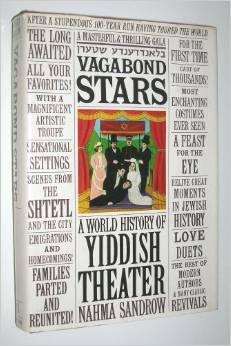

A classic study of Yiddish Theater: “Vagabond Stars.”

On Tuesday night, Mr. Kosky sat down at the grand piano himself, on the empty big stage, and explained what Yiddish Operetta is, that it comes from Eastern Europe and was created there in the 1880s before becoming a sensation in New York. In the US, Yiddish Operettas blossomed in the 2nd Avenue Yiddish Theater district. And Barrie Kosky mentioned that various members of his own family, back in London in the 1920s, worked in Yiddish Operetta as composers and conductors. Kosky Jr. then segued into 14 numbers from various operettas and operetta films, ranging from the 1880s to the 1930s. His dazzling piano playing was characterized by a deep understanding for the great (and sensual) rhythms of these songs, and an ear for the joyful little accompanying figures in the right hand. This was a remarkably relaxed, yet energetic at the same time interpretation of this music. Because of his tongue-in-cheek narrative in between, Kosky had the audience wrapped around his little finger the whole night.

It helped, of course, to have two such sympathetic soloists as Helene Schneiderman from Stuttgart and Alma Sadé from the Komische Oper ensemble.

They could have been a mother-daughter team. I personally found Schneiderman’s rendition of the songs a little too “artificial,” not sounding “dirty” and linguistically flexible enough. But she was fun to listen to, no doubt about that. Sadé, on the other hand, had an air of the young Bernadette Peters about her, and I am not saying that because of the wild curly hair, but because of the fragile way she moved and sang her songs with a husky soprano that was truly affecting. Sadé positively glowed on stage. I wondered if that had anything to do with her pregnancy. Whatever it was, it was spell-binding.

Towards the end, both divas gave a rendition of the famous “Rozhinkes mit mandel’n” lullaby. It’s from the 1880s – from Goldfaden’s Yiddish Opera (!) Shulamith oder bas Jeruscholaim (Sulamith or the Daughter of Jerusalem) – but was sung by many mothers to their children in concentration camps. The voices of the two divas blended in spooky (and perfect) harmony. They were so touching in this duett that you could have heard a needle drop in the auditorium. However, as Kosky pointed out, the sorrow often dealt with in these Yiddish songs does not stem from experiencing Nazi horrors, but reflects the pogroms experienced in Eastern Europe in the late 19th century. The horrors described in the musical Fiddler on the Roof – which is bound to make its way to the Komische Oper as Anatevka before too long. (Maybe with Mr. Kosky as Tevje? Would be dream casting.)

In 1926, developer Louis N. Jaffe had the Yiddish Art Theatre built for actor Maurice Schwartz, “Mr. Second Avenue”. The area was known as the “Jewish Rialto” at the time. It was designated a New York City landmark in 1993. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The last number of the evening was the hilariously funny “Rumania, Rumania!” by Aaron Lebedeff, a hymn to the beauty of Rumania – which, as Kosky pointed out, was one of the most inhospitable places in the world for Jews. That did not stop the writers from turning it into a knock-out song, sung in a knock-out way by Sadé and Schneiderman.

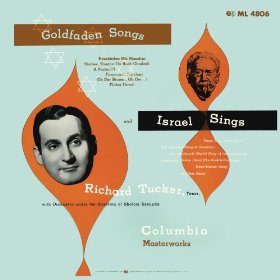

A classic disc of Richard Tucker singing Goldfaden’s songs.

The program gives a very good overview of Yiddish theater songs in an essay by Jascha Nemtsov. If you want to know more about the subject, try the classic Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater.

Having wet our appetites now, the next thing at the Komische Oper should not only be Moses und Aron by Schönberg and Anatevka, but the opera Shulamith oder bas Jeruscholaim. And since the late-night setting of this intimate recital was so convincing, and winning, it would be great if it could become a regular feature at the Komische. Considering Barrie’s piano playing skills, how about more operetta songs, Yiddish or otherwise? There is a wealth of music once performed in the cabarets inside of operetta theatres, such as Die Hölle in the Theater an der Wien, repertoire mostly forgotten today but well worth rediscovering. The dimmed auditorium of the Komische, on any late-night in Berlin, is the perfect place for such discovery concerts.

So, all I can say is: “Barrie, spiel auf!”