Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

9 December, 2015

Today, soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf would have celebrated her 100th birthday. That’s a perfect occasion to remember her enormous recorded legacy, also from an operetta point of view. Because her one (and only) operetta recital on disc is a bench mark for any “operatic” soprano daring to cross the border into operetta land. And her various recordings of complete Strauss and Lehár operettas remain reference points in the general discography of operetta. Her recital is part of the newly released box by Warner Classics (“The Complete Recitals 1952-1974”), and her complete operettas have been in circulation on various labels, from EMI to Naxos.

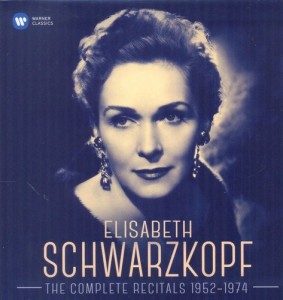

Portrait of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. (Photo: Angus McBean/Warner Classics)

The German music critic Manuel Brug headlined his birthday article with “Töne wie Zuchtperlen,” hinting at what made Schwarzkopf’s singing so unique and special: the absolute artificiality. Every single note and phrase was turned into artifice by her, in a way that no one else has done since. The results are particularly happy when this concept is applied to the anti-realistic art form operetta. Schwarzkopf caresses each phrase and plays with the words, insinuating meanings that are lost in many other recordings. Take, for example, her husky “Komm mit mir ins Chambre separée” from Heuberger’s Opernball. Schwarzkopf makes it very clear that this is all about seduction and sex, but she only hints at it. It’s the 1950s, after all. But it’s a technique she learned from Fritzi Massary who worked in the much more liberated 20s. Schwarzkopf’s husband Walter Legge made her listen to Massary’s recordings, so she’d learn how it’s done. And Schwarzkopf learned, because she understood the essence of Massary’s singing. But she did not merely copy the great diva of the previous generation – she applied the Massary style to her own voice and came up with a unique and highly distinctive personal style of her own. Which is what all great artistry is about. (She also applied this style to her famous Marschallin, which is deeply indebted to Massary, too.)

Considering how many opera singers think that simply singing this music with a “great” opera voice is enough, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf is a shining example of how to do it better.

Operetta singing is not about “pretty voices” but about finding a unique personal style, whatever that might be. And very few modern day opera singers have such a personal style.

Schwarzkopf also demonstrates how word-play makes operettas fun and worth listening to. Take her entry as Hanna Glawari in Lustige Witwe. If you’ve ever heard Schwarzkopf on her first recording sing “Gar oft hab’ ich gehört, wir Witwen ach, wir sind begehrt … erst wenn wir armen Witwen reich sind, ja dann haben wir doppelten Wert” you are not likely to enjoy any (!) subsequent version by Felicity Lott or Cheryl Studer (or Renée Fleming). They simply sound boring by comparison, even though they basically have the same lyric soprano voice.

In the days before 1933, the German language operetta scene offered many highly unique voices and personal styles for this repertoire. Next to Massary, there were Richard Tauber and Gitta Alpar in the grand opera department, but also the many knock-out comedians like Max Hansen, Siegfried Arno, Rosy Barsony or Oscar Denes. (To name only the ones still familiar today.) After 1933, this multitude of options in operetta singing was somewhat streamlined. And in the 1980s, any sense of style in operetta singing was lost, which is documented by the majority of shockingly inadequate operetta recordings and modern day performances.

The Complete Recitals by Schwarzkopf, on Warner Classics.

In an interview, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf recalled how she, as a student in Berlin, attended a class in which recordings by famous artists were played. She said that she sat there, listening to great singers on Schellack and wondered why on earth they were so famous. Until that one moment came, that one note, that one vocal effect – that made it clear why these people were famous. Schwarzkopf understood that great singers always needed to find such moments, such effects, so stand-out notes. And she did, also in her operetta recordings.

Commemorating her 100th birthday would be a good opportunity – for all the striving young (and old) operetta singers out there – to listen to Schwarzkopf’s recording again and learn why they are so effective. And see what they could copy for their own singing, by adapting these elements for their own voices. Because just getting up there on the stage and singing meaningless notes, without any consideration for the “Art of Operetta,” is like musical analphabetism. And that is something no one can accuse Miss Schwarzkopf of.

She learned from the greatest artists of the past, and became one of the most unique operetta singers of the post-WW2 period: a counterpart to all the Anneliese Rothenbergers and Margit Schramms or Ingeborg Hallsteins. (For who she had to speak [!] the dialogue scenes in the Fidelio recording on EMI.)

If you want to read a great article on Schwarzkopf’s recorded legacy, we recommend Rüdiger Winter’s review of the Warner Classics Recital Box on Operalounge.de. It’s a one-of-a-kind article, just like Schwarzkopf’s singing. Happy birthday!

thank you – considering that she did not particularly like operetta as such she does a heavenly job on this recording. and what an artist she is! she is unique and wonderful and – as the word says – an extraordinary artist, a creator-ess of art!

The outstanding operetta soprano of our times. Amongst other things.