Steven Ledbetter

The Boston Musical Intelligencer

12 January, 2016

An unlikely current hit, the 1923 Yiddish musical Di goldene Kale (“The Golden Bride”) by Joseph Rumshinsky, emerged after years of research sparked by a score found in the Harvard Music Library in an excellent production by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene at the The Edmond J. Safra Hall of the Museum of the Jewish Heritage. I found the show as delightful and satisfying as anything in town, and I was not alone. The New York Times gave it a very warm review and included a video clip of excerpts from several of the songs, which gives a taste of the work and the production.

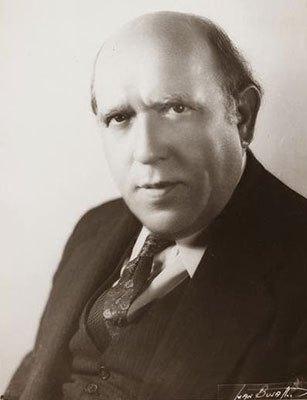

Composer Joseph Rumshinsky (1881-1956).

Though the original month long run is over, there was talk of possible performances in Philadelphia and perhaps elsewhere, and of a commercial recording or even a DVD. I have been following the development of the scholarly project from its origin at the Harvard Music Library to its unexpected flourishing in New York, and since almost no one knows the composer or the music any more, I offer this article as small glimpse at a rich and largely forgotten part of the American musical theater.

During the first decades of the 20th century, Yiddish theater was wildly successful, especially in New York, where a large population of recent immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived in the course of about three decades. Most of them spoke Yiddish, a language that, like English, was an amalgamation of many diverse sources—in this case from central and eastern Europe, including a strong helping of German, colored with overtones of the Russian, Polish, Lithuanian, Rumanian, and holdovers from Hebrew, among others.

Yiddish became a lingua franca for arrivals from many parts of eastern Europe where the authorities were doing their best to drive Jews out.

In America, these newly arrived immigrants, like newcomers from other cultures and countries before them, faced the challenge of learning a new language and new cultural practices while holding on, as best they could, to the familiar and well-loved practices—social and religious—of the place from which they had come.

From the 1890s through the 1920s, the new immigrants needed to find a footing in their new home, which they did through a fusion of old experiences and new. The theater offered one readily available way for speakers of a certain language sharing a certain culture to confront the novelty of the New World while attempting to preserve as much as possible of what they had brought with them. The Yiddish theater, a quite new tradition founded in eastern Europe in the 1880s and largely suppressed by Tsarist command, provided entertainment and diversion, examples of lifestyle successful and otherwise, and instruction in what they might expect in America.

The original Playbill for “Di goldene Kale,” 1923. (Photo: Steven Ledbetter Archive)

Some of the stars became extraordinarily famous, at least within their own ethnic circles. Two of the greatest stars were Boris and Bessie Thomashevsky, who were idolized by a large following including the young George Gershwin, for example, but remained all but unknown outside the world of speakers of Yiddish. (Boris and Bessie were the grandparents of Michael Tilson Thomas, and for most people who did not grow up in the areas of New York City that house the majority of newly immigrated Jews, their first significant connection to the tradition would most likely have been a concert program—essentially a lecture with performance by singing actors representing Boris and Bessie—assembled and conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas over the course of the last decade, eventually broadcast on PBS (“The Thomashevskys: Music and Memories of a Life in the Yiddish Theater”; the trailer can be viewed here.

And then there were others who reached to general audiences such as Molly Picon, and Jacob Adler, whose daughter Stella taught method acting to Marlon Brando, Robert DeNiro and many others.

Molly Picon in a Yiddish Theater production, 1919.

Early in the 20th century, Boris Thomashevsky hired a young composer newly arrived from Vilna, Lithuania, by the name of Joseph Rumshinsky (1881—1956), who would go on to become perhaps the most significant of all the composers for the Yiddish theater, whose success was so great that he came to be dubbed “the Jewish Victor Herbert.”

Rumshinsky was among the first generation of major composers for the Yiddish theater discussed by ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin of Wesleyan University in his book Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants (U of Illinois Press, 1982), which seems to be the only substantive study to date of the musical aspect of Yiddish theater. This early group of composers grew up in Eastern Europe with the musical traditions of the shul [synagogue] and the khazn [cantor] who would accept a musical boy as a meshoyrer [choirboy]. If his talent proved sufficient, he would receive singing lessons and later learn to read music and study elements of theory and composition, thus establishing a framework for a career.

The young Rumshinsky proved so apt at advanced instruction that he was nicknamed “Yoshke der notnfresser” (Joey the note gobbler). He recalled later that these musical experiences related to the worship tradition “were, for Jews, the opera, the operetta, and the symphony.” A later generation of composers of Yiddish song in America, whose training was more secular and theater-oriented, became generally better known when some of their songs (like Sholom Secunda’s 1932 “Bei mir bist du sheyn”) became popular in the general musical culture of America.)

Yiddish theater composer Joseph Rumshinsky as a young man.

Despite his later success as the principal composer for the Yiddish theater in America, Rumshinsky is missing from the New Grove both in the 1980 and 2000 editions, and in the first edition of The New Grove Dictionary of American Music. He finally appeared, which a short article—but no list of works, reputedly including some 90 musicals—in the 2nd edition of the American Grove.

Given the lack of widely available information about him, I will briefly recount some essential details of his background, derived from Slobin’s book, which also quotes from the composer’s memoir (excerpts will appear in quotation marks here).

Rumshinsky’s father was a hatter, but a musical man who encouraged his apprentices to sing—sometimes Hebrew songs that he would translate into Yiddish and then “improvise the music in his own special way.” If business was bad or there were other troubles impending, they would sing passages from the Psalms “with the harmony of the apprentices: it would melt your heart with its sweetness and sadness.” But if the hat business was going well he would lead a call-and-response type of song with everyone joining in. “The happy songs consisted of half-Russian, half-Polish, mixed in with Yiddish and Hebrew, and the work would follow along with the tempo and mood of the music.” Rumshinsky’s mother was a singing teacher—“Not, God forbid, for money!” She taught wedding songs to the local girls. The description makes clear that this was a highly eclectic society in social and musical terms.

The boy Yoshke was taken to the cantor in Vilna, where he sang and heard a full choir for the first time, to his great delight. A musical career was clearly indicated. He persuaded his father to enroll him in a school with a secular education, where he reportedly learned to read music in a month and began learning the piano. From this point on until his move to America, he pursued different kinds of musical activities, sometimes writing for the synagogue, and increasingly finding himself drawn to the theater. He was excited by a performance of Shulanis, a play by Abraham Goldfadn, founder of the Yiddish theater in Lithuania about 1880. But once that tradition was banned by the Tsar, it could only flourish in the New World. Meanwhile, he lived a vagabond musical life, learning music from various traditions, including Russian operetta and German songs. In Lodz he formed a nationalist Jewish chorus which had to suppress its overt nationalism to avoid problems with the tsarist police, and which scandalized the older generation because boys and girls sang together.

Abraham Goldfaden (1840-1908), author of the famous lullaby “Rosinkes mit Mandle.”

The threat of being drafted into the Tsar’s army motivated a rapid escape to London and, not long after, to New York. There his eclectic background was helpful. He was first hired to train a chorus to sing Rubinstein’s opera The Demon in Russian, and to provide a new orchestration because it would be difficult to get the materials from Russia. He also began turning out easy piano pieces for S. Goldberg, a music publisher with a store on the Lower East Side. He gave piano lessons to a wide range of immigrants, many of whom had bought a piano in their aspirations to the middle class. (The Gershwins were one such family who bought a piano, intending it for the shy, bookish Ira; but the minute it was hoisted through their apartment window, his brother George took over and never let go.)

But the move to New York also brought Rumshinsky to the region where the Yiddish theater was thriving. Not long after arriving, he was hired by Boris Thomashevsky to work on his shows, thus beginning a long career resulting in dozens of musical shows and other music as well, including a serious opera, Ruth, in the late 1940s, which remains unperformed.

Regina Gibson, Jillian Gottlieb (Khanele), and Amy Laviolette in “The Golden Bride.” (Photo: Ben Moody)

It is the 1923 hit show Di goldene Kale (The Golden Bride) that has just been elegantly and cleverly revived in New York in a beautifully produced version with exceptionally fine presentations of its songs and dances, that has motivated this essay. Coming as it did right at the close of the period of free and open immigration from eastern Europe, the show’s libretto must have seemed quite modern, with two contrasting acts involving characters in their homeland and most of the same characters making a new life in the United States. At the same time it links to the grand operetta tradition. Most striking to me was the similarity to a basic situation on Lehár’s The Merry Widow: The female lead is an unmarried woman with great wealth (in Lehár she is the widow of a very rich man; in Rumshinsky, she is a poor Jewish girl who has been separated from her mother but whose recently-deceased father had gone to America and made a fortune). In the Yiddish show, Goldele feels that her mother must still be alive somewhere, and she promised to marry the suitor who can locate her (despite the fact that she has a favored sweetheart).

The path to the revival was a long one, taking some six years of scholarly work. Sources for plays and musicals produced in Kessler’s Second Avenue Theater and other houses devoted to the Yiddish tradition have mostly been lost or scattered. The first job is simply to locate the large amount of missing material.

The first impetus to undertake the reconstruction of “Di goldene Kale” was a conference of scholars of American music in Boston area in 1984, when Michael Ochs, then the Music Librarian at Harvard, found a manuscript copy of the piano-vocal score of Rumshinsky’s “Di Goldene Kale.”

As is common with such scores, no spoken dialogue is included, and there is no inkling of what the orchestral score might be like. But he put the score on display in an exhibit for the annual conference of what was then called the Sonneck Society (now the Society for American Music).

After retiring from Harvard, he decided to make a project of the operetta and began translating the lyrics. At the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York (which contains an extraordinary collection of materials relating to the Yiddish theater), he found a typescript of the libretto amid the papers donated by the grandchildren of the librettist Frieda Freiman and children of the actress Flora Freiman.

Adam Shapiro (Kalmen) and Company in “The Golden Bride.” (Photo: Ben Moody)

What made it possible to reconstruct the full score was a gift of manuscripts from Rumshinsky’s estate deposited at UCLA by his children, Murray Rumshinsky and Betty Rumshinsky Fox. Here Ochs found the lead sheet (not a full orchestral score!) from which the composer conducted the 1923 premiere, and all the individual orchestra parts. These materials allowed him to recreate the full musical score by copying all the individual parts together. (An opera conductor would never work without a score at the Met, but it is very rare for the conductor of a commercial show to have anything more elaborate than a piano score.)

One irony in all this, as Michael Ochs has smilingly described on several occasions, is that he comes from an older immigrant Jewish family of German roots, a group of people that in the late 19th century tended to look down on the impoverished newcomers from the shtetels who didn’t even speak proper German! His forebears would not have deigned to attend the shows at the Second Avenue Theater. Yet a century later, he has become the prime mover in rediscovering the brilliance of Joseph Rumshinsky and his delightful 1923 hit. Now that the score has been rebuilt, it will appear in the series Music in the United States of American (MUSA), published by the American Musicological Society and will be the first scholarly performing materials of any Yiddish musical ever made available. According to Michael Ochs, Rumshinsky and this operetta “played an important role in the development of the American musical. Irving Berlin, Yip Harburg, and the Gershwins, among many other Broadway and Tin Pan Alley personalities, regularly attended Yiddish theater shows.”

Cameron Johnson (Misha), Rachel Policar (Goldele), and Company in “The Golden Bride.” (Photo: Ben Moody)

The delightful opportunity to actually see and hear the results of all these years of scholarly endeavor came about through the assistance of Chana Mlotek at YIVO, who introduced Michael Ochs to her son Zalmen, artistic director of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, who became the music director of the production. First the show was presented in a minimalist way with a piano-accompanied performance of the songs in May 2014. Then the score was performed with orchestral accompaniment at Rutgers University in August 2015. The obvious quality of the show as heard in concert led directly to the fully staged production, co-directed by Bryna Wasserman and Motl Didner from December 2, 2015, to January 3, 2016. Some 300 singer/actors auditioned for the show for the eight solo parts and ensemble, which gave the leeway to assemble a superb cast, one adept at the demands of opera as well as ethnic kitsch. The theme song [here] offers some of the flavors of this stylistic melting pot; the recording from which this track comes is the last in a series of songs of the Yiddish theater issued by Naxos in its important series Jewish Music in American Life; this particular CD includes nine Rumshinsky songs from nine different shows, a welcome introduction to the work of this master of the musical theater.

The Edmond J. Safra Hall was bedecked in a stylish garden which served as the shtetl in Act I, before morphing to our great amusement into an elegant New York apartment for Act II. The way the shtetl shtick became 2nd Avenue shtick provided one of the chief amusements. The character types were well realized, to an extraordinary level of detail. Played by Glen Steven Allen, the American cousin Jerome even coached his Yiddish to feature an American accent. The portly Adam Shapiro memorably impersonated Pavlova in the costume ball. Zalmen Mlotek conducted the 20 or so players with real affection and stylistic verve. The placement of the orchestra behind a scrim gave them the opportunity emerge at appropriate times.

Glenn Seven Allen (Jerome), Adam Shapiro (Kalmen), and Company in “The Golden Bride.” (Photo: Ben Moody)

As a musicologist who has sometimes spent years editing dusty materials, I know the feeling of seeing a scholarly project that results in a handsome volume of printed music that no one is performing—thus largely undermining the purpose of all the effort. But in this case, the happiest of circumstances made it possible for this long, complex project to be both heard and seen by thousands—and one hopes, through future productions as well.

Steven Ledbetter is a free-lance writer and lecturer on music. He got his BA from Pomona College and PhD from NYU in Musicology. He taught at Dartmouth College in the 1970s, then became program annotator at the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1979 to 1997.

To read the original article, click here.