Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

15 May, 2022

The Theater Vorpommern is a company that plays in various cities near the Baltic Sea in North-East Germany. Its opera director, and chief stage director for musical theater, is Wolfgang Berthold. He’s put Ralph Benatzky’s 1930 Meine Schwester und Ich on. It premieres on May 20 in Stralsund. David Behnke conducts the chamber piece and Franziska Ringe takes on the role of Dolly, the princess who goes to work in a shoe shop – to win over her man, Semjon Bulinsky as Dr. Roger Fleuriot, a penniless academic who can’t stand the idea of marrying someone who has more money and a higher social position than he. It’s a piece about changing social norms and accepting that change. We spoke with Wolfgang Berthold about his production and with operetta expert Philip Lüsebrink who plays Count Lacy – the “other” suitor.

Wolfgang Berthold (l.) and Philip Lüsebrink. (Photo: Private)

Stralsund is a small city in former East-Germany. You’ve presented Die lustige Witwe this season, followed now by Benatzky’s chamber piece Meine Schwester und Ich. What relevance do operettas have for you, as opera director, at Theater Vorpommern? Why do you consider the genre relevant for your repertoire – and for your local audience?

Wolfgang Berthold: Operetta has a naturally fixed place in the programming of such a theatre, and it has a regular local audiencehere. This, of course, includes the usual expectations and misunderstandings. Titles outside or beyond the standard repertoire (such as Meine Schwester und Ich) have a much harder time being acknowledged, and then, the ideas of what operetta should be, does not always have anything to do with the original format of the works. So the challenge is, on the one hand, to not completely disappoint expectations (because what would be gained by doing that?), and on the other hand to emphasize the political, cataclysmic, anarchist elements inherent in this genre, making them interesting for the audience. Operetta (especially the works composed after 1910) has always been a “genre of crisis”, and thus it seems to me more topical than ever.

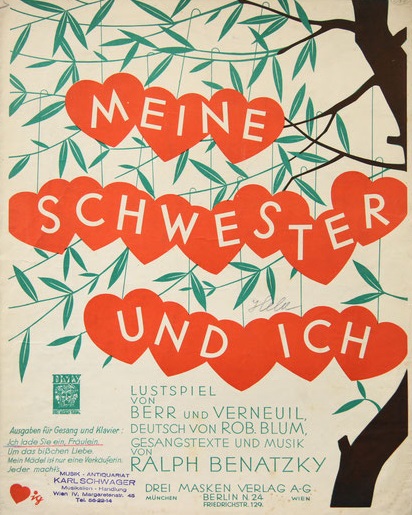

1930 sheet music cover for “Meine Schwester und ich.” (Photo: Drei Masken Verlag / notenmuseum.de)

Philip Lüsebrink: Especially operettas written after 1910 can be seen as political cabaret, they are irony-fueled entertainment with a strong social message, and that’s worth showing today. The jazzy and syncopated elements in the music are quite irresistible, and people are often surprised by this today, asking: “Oh, that’s an operetta?” When you highlight these points in a performance operetta can be “dust-free” fun for all generations.

Many people will agree that DDR operettas is the style of “Socialist Realism” are a mirror of their times and ideology. With pieces by Lehàr and Benatzky, audiences (and stage directors) are often less focused on the historic background. Why do you think that is so – and what are we missing by not acknowledging how “modern” pieces such as Witwe or Rössl or Schwester once were?

Berthold: For me, the historical background is crucial to understanding Lustige Witwe in particular, but also for understanding Schwester; of course, this context is only partially comprehensible to today’s audiences. For example, both works have extremely emancipatory aspects, and I have tried to make this clear in both productions. Sometimes you just have to incorporate some background knowledge: in our version of Witwe, the dialogue of Njegus is used to reflect and describe the political situation in the late phase of the European monarchies, the increasing militarization and the sometimes cautious, sometimes daring actions of the ruling class. Incidentally, in the last few weeks of our performances these comments became – once more – very contemporary.

Lüsebrink: I think a big misunderstanding is that operetta is never seen as more than “nice music”, supposedly only loved by “old people”, full of stories with a trivial happy ending, offering audiences a chance to get away from the hardships of daily life. But operetta is so much more. When you put dialogue, costumes and decoration in the right place to emphasize the historical context, you have a feel-good-factor for people who expect “what they know” plus a possible debate of gender roles, sex, politics, racism, colonialism etc..

Franziska Ringe as Dolly and Philip Lüsebrink as Lacy in “Meine Schwester und Ich”. (Photo: Peter van Heesen / Theater Vorpommern)

Barrie Kosky at Komische Oper and Gorki with their Alles Schwindel, as well as Tipi with Frau Luna, have shown that it can be inspiring to cast operettas with “new” types of actors who break free from the post-war tradition of using opera singers for the genre. What’s you opinion on operetta casting?

Berthold: It is, in fact, a big problem that there is little focus on operetta in the current system of musical education and thus little understanding of the genre among singers. Fortunately, for our production of Schwester I’ve been able to put together a cast of operetta-savvy performers from our regular ensemble, plus an actor, and with Philip we also have a genuine operetta specialist with whom we, at least in my opinion, can try to create a wild, unsentimental and “authentic” style. Of course, something like this is not always possible, especially with small ensembles that have to accommodate a great many styles. I hope, though, that the pioneering efforts you mentioned will at least heighten awareness for the way the genre can be done and, in the long term, stimulate interest in an updated approach to operetta among young singers. Also, a rejuvenation of the audience for operetta is urgently needed, especially outside of major cities.

Lüsebrink: Unfortunately, many classical singers in operetta focus only on “singing” and producing beautiful notes. Quite often they are not trained in doing dialogue or telling stories with lyrics, music and body movements. Actors or singers for the world of musicals are used to look at the text first. In 2003 I was be part of Großherzogin von Gerolstein at Deutsches Theater Berlin. The cast included Dagmar Manzel, Max von Pufendorf, Michael Prelle, and Timo Dierkes. It was truly amazing. A mixture of singing, acting, dancing. And it was a huge success, that paved the way for Manzel’s incredible operetta career at Komische Oper. You need more than pure opera singers do turn these pieces into all-round convincing spectaculars.

Benatzky and his first wife Josma Selim in Berlin, in the 1920s. (Photo: Archive of the Operetta Research Center.)

Philip, you are going to play Count Lacy in the new production. What are the special challenges for you when you perform operetta, as opposed to musicals, opera or cabaret?

Lüsebrink: During the last 20 years I performed in operas, musicals and cabaret. But my favorite genre has always been operetta. The combination of singing, speaking with music, dialogue, dancing, moments of sentiment and intimacy, the mad-cap elements, all that really fascinates me, also the fact that you need to present everything with a wink in your eyes. Nothing is real, and at the same time it is. I learned a lot from great operetta performers and directors. I still try to attend as many operetta performances as possible. I think the big challenge in performing operetta is the mix of disciplines and the need to understand the historical background. You should know the “original” style and intentions of this genre before you start performing it in 2022. Sadly, young opera singers rarely bother with that, because no one stimulates them in that direction. I knew Schwester and already sang some of the music in concerts, but I never performed the complete show on stage. I am happy to be part of this production now, with a fresh approach by Wolfgang, David Behnke our conductor, and with beautiful sets and costumes by Stefan Rieckhoff.

What’s the special fun to be part of an operetta production?

Berthold: I find the ability to laugh at the world in the shadow of cataclysmic events, expressed in the operettas of the 1920s, healing and refreshing, especially in light of the current situation. Much of what we think of today as supposedly socially established norms seem to be handled much more organically in the works of this earlier time (such as queerness, the breaking with gender norms, more liberated concepts of life and love, etc.).

Lüsebrink: I totally agree.

Pihla Terttunen, Philip Lüsebrink, Semjon Bulinsky, Alexandru Constantinescu, Andreas Sigrist and Franziska Ringe (left to right) in “Meine Schwester und Ich.” (Photo: Peter van Heesen / Theater Vorpommern)

At Gorki, Komische Oper and Tipi the actors have shown that it is essential for the success of operetta to be able to perform dialogue with bravura – and as a fully integrated element of the “Gesamtkunstwerk”. Why is this still rarely acknowledged by casting directors? And what do you do with an operetta when you don’t have performers who can “do” dialogue?

Berthold: Practice, practice, practice… Of course, the problem needs to be addressed at an earlier stage in the process, because otherwise you end up with a systemic error being carried on the backs of the performers, who aren’t actually responsible for it. When auditioning for permanent ensemble positions, we asked the candidates to prepare a number from an operetta and a spoken monologue, because we knew we would be performing this repertoire. It is, however, remarkable how many artist agencies were irritated by the latter requirement…

And what about dance? Do you need an Otto Pichler in Vorpommern?

Berthold: Luckily we have a great ballet company and Adonai Luna is a ballet director who knows and values the work of Otto Pichler. It’s easy to talk with him about certain styles. The “Grisette” number in Witwe, for example, was expanded into a large revue scene that references the cancan, but then moves far away from it. I take it as a compliment that a newspaper wrote that there was “too much eroticism involved” in this number… Schwester is a chamber operetta with six performers, in which the genre of revue is only parodied in passing (after all, it’s set in a shoe shop). But of course our production isn’t completely without dance.

Franziska Ringe as Dolly and Semjon Bulinsky as Roger in “Meine Schwester und ich.” (Photo: Peter van Heesen / Theater Vorpommern)

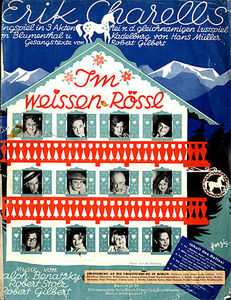

Meine Schwester und Ich premiered in 1930, a few months before the famous Im weißen Rössl. What’s the difference between this Benatzky and the other one?

Lüsebrink: I played Rössl in six different productions. Leopold, Siedler and Sigismund. The focus was always on revue numbers and dancing. The dialogue was never more that something leading up to the next big musical number. In Schwester I have more dialogue than music. For Count Lacy the music is supporting the dialogue. But, of course, I have a beautiful duet.

Sheet music cover for “Im weißen Rössl” 1930.

Berthold: Actually, one would rather assume that Schwester was written after Rössl, because some of it seems like an ironic comment on the later work. The main difference seems to me to be that in Rössl the revue numbers are in the foreground, and the plot, with its many characters and story lines, ultimately serves as a pretext for the musical numbers. In Schwester, which is based on a boulevard comedy, the absurd and complicated plot has more intrinsic value. Also: Rössl parodies Alpine tourism, while Schwester parodies the genre operetta itself. One could almost call it a meta-operetta.

Do you see typical themes from the Weimar Era in the show?

Lüsebrink: Count Lacy enjoys life, love, drama, and hedonism. He is attracted to Dolly, Irma, Roger and everything that brings amusement.

Berthold: The conflict between Dolly and Roger is one of class and is directly identified as such. The decisive question is: can such class differences be overcome or not? Furthermore, this becomes a gender conflict, in which the roles are suddenly reversed: Dolly is presented as a modern, self-determined and financially independent woman who would have no problem with the idea of supporting her husband – however this becomes a problem for him. Irma, a woman trying to get by with two jobs and pursuing her plans purposefully, is a prime example of the new role models of the 1920s. Indeed, the piece is almost a history lesson.

Franziska Ringe as Dolly in “Meine Schwester und Ich.” (Photo: Peter van Heesen / Theater Vorpommern)

It’s called a “Musikalisches Lustspiel” and close, in style, to the new musical comedies Jerome Kern wrote for the Princess Theatre in New York. Would you say Schwester is an early example of a German “musical comedy”? And how does it compare to Kern and Gershwin etc.?

Berthold: In fact, I see Schwester as a kind of link between operetta and musical, which was also one of the reasons for putting it on here. However, I keep noticing that musical comedies (and even more so more recent musicals) lack one vital characteristic of operetta: self-irony. And Schwester is really full of that.

Jerome Kern in 1918, as seen in the “New York – Musical Courier,” Volume 77 Number 13.

Your choice of titles is still firmly rooted in history. Would you consider playing modern operettas such as The Beastly Bombing (2006) or Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre (2021) at Theater Vorpommern?

Berthold: In general, I never want to rule out anything, but I actually have my doubts that operetta can be revived in this form. Ultimately, due to the brutal rupture caused by the events of 1933, it is historically a very clearly defined genre that could perhaps only have developed in this form at that precise time. But of course I’d be happy to be proven wrong.

Your Benatzky production opens for Pride Season in Germany, on your company’s homepage there are a lot of rainbows to be seen. How important is diversity and the representation of so called “minorities” for your theater, in the productions, in the communication, in the way your present yourself to the world?

Berthold: In the daily reality of life at our theatre, this is pretty much standard and nothing special, yet at the same time we are aware that in Western Pomerania we can and must take pride in this. We opened the season with our own interpretation of Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf, in which we cast a mezzo-soprano in the title role to free ourselves from the racist pitfalls this work contains. We were thus able to address the questions raised by concepts of otherness and the treatment of minorities in a way where we didn’t run the risk of appropriation, while at the same time redefining the piece as a queer one. This issue is of vital importance for me in all my productions: how can we deal with our cultural heritage, presenting and interpreting today what was formerly avant-garde, without retreating to “that was just the way it was” and thus allowing outdated concepts to remained unchallenged?

Philip Lüsebrink. (Photo: Daniel Schliewa)

Why do you think so many operetta companies around the world still shy away from “diversity” (Kosky excluded) and also avoid including operetta serious debates about feminism, racism, colonialism, gender and sexuality?

Berthold: First of all, there’s the fear of being rejected by audiences (because we depend on their acceptance). Then there can also be defensive reactions to these issues amongst the performers, which I even experienced to some extent while producing Witwe. Operetta can be suggestive, insinuating, even racy – but please only in a heteronormative way, some seemed to think. However, I believe that this form of theatre will only survive if this thematic exploration, which is actually implicit in the genre, succeeds and a new audience can be inspired by it, not just a heteronormative one.

Wilhelm Bendow in 1929; he was the star of many Erik Charell productions at Großes Schauspielhaus in the 1920s and famous for playing “Nance Characters.” (Photo: Operetta Research Center Archive)

Lüsebrink: I absolutely agree. And we have the problem again that so many actors and directors don’t take operetta seriously. It is not the funny, easy, and trivial genre many think it is. It can be current, ironic, and open in every direction. Think out of the box!

What are you next operetta plans, in the following seasons?

Berthold: Since our house in Greifswald is being renovated, we will unfortunately not be able to produce a new operetta next season, but Schwester will run for the whole season and hopefully attract many visitors. In the season after that there will certainly be a new operetta production. I can’t reveal more at the moment … so stay tuned.

For more information on the new production and performance dates, click here.