Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

1 October, 2018

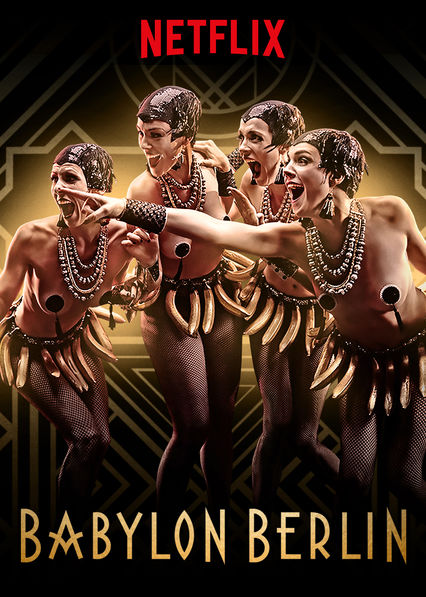

Is Korngold’s 1920 psycho thriller Die tote Stadt an operetta? Obviously not, but there are various links to the genre, not just since Jonas Kaufmann included “Glück das mir verblieb” in his operetta album Du bist die Welt für mich in 2014. Biographically, Korngold went on to work at Theater an der Wien after the success of Tote Stadt and started an important revival of Johann Strauss operettas, most notably with his version of Eine Nacht in Venedig in 1923. It starred Richard Tauber for who Korngold arranged the new song “Sei mir gegrüßt du holdes Venezia.” Tauber was also one of the most important singers of the role of Paul in Tote Stadt. Which might surprise many today, because we associate the killer part with Heldentenors, not with sensuous lyric singing à la Tauber. Now, Komische Oper Berlin has opened its new season with Die tote Stadt and a new production by Robert Carsen. In his post-premiere talk, artistic director Barrie Kosky stressed that he sees this opera in the context of his other 1920s resurrections: Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten last season, but also his various operetta excavations by Abraham and Oscar Straus. All of these shows represent the same ‘lost world’ of Weimar Republic Berlin which has become a ‘hot’ issue again, not least because the successful TV series Babylon Berlin has fascinated many viewers of late. (It is due on public TV in Germany shortly and currently advertised all over Berlin, it’s also due on Netflix.)

Sara Jakubiak as Marietta surrounded by suitors in “Die tote Stadt” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

Casting the tenor role of Paul with an outstanding operetta singer with magnetism and star quality has its advantages. Not only Tauber demonstrated this with his melting version of “Glück das mir verblieb.” Also, years later in 1952, Karl Friedrich was an amazing Paul in the Munich recording conducted by Fritz Lehmann. Like Tauber, Mr. Friedrich uses many a surprising pianissimo, falsetto, and lyrical phrase where others (like René Kollo on the RCA recording) just strain the top of their voices. And the listener’s ears. Komische Oper offers Aleš Brisein as a tenor who goes down this lyrical road too: with haunting effects, again and again. However, he does not possess the voluptuousness of Tauber’s voice, the sudden attack, the way Tauber overwhelms the listener (also in his many Lehár interpretations) with just a single phrase. By the end of the evening, when the tenor is left alone on stage – ready to be taken away by psychiatrists in white coats – he sings the famous “Glück” tune once more. It’s almost identical with the end of Land des Lächelns where Tauber sang “Immer nur lächeln” one final time for tragic effect. At this point of the show, Briscein did not have much lyricism left to turn the moment into an unforgettable cri de coeur. More operetta ‘kitsch’ (in a positive way) would have been fitting here.

Franz Lehár with his star tenor Richard Tauber who premiered all of Lehár’s last operettas.

The same could be said of Günter Papendell who looked dashing, as always, but didn’t sound quite so dashing with his serenade “Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen, es träumt sich zurück.” The melodic lines of this slow waltz were not clearly sketched, even though the staging of the serenade, and the entire commedia dell’arte scene, was dazzling with glittering costumes and sets, turning Bruges-la-Mort into a very Berlin-style 1920s dream in which Marietta comes flying down from the ceiling on a chandelier, with silver confetti raining down from above. It was magical!

(It also looked like a loving homage to the many Kosky productions that utilize the same glitter-and-be-gay aesthetic. Needless to say, I loved it.)

Sara Jakubiak as Marietta flying down on a chandelier in “Die tote Stadt” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

As Marie/Marietta the Komische Oper offered Sara Jakubiak who had scored a major success as Heliane last season at Deutsche Oper Berlin in Korngold’s Das Wunder der Heliane. There, her big warm voice soared above the massive orchestral forces in hypnotizing passivity. Here, as Marietta in a much smaller auditorium, her voice somehow didn’t blossom in the same glorious way. And the many parlando passages didn’t come across as casually seductive as they might have. Back in the 1920s, Maria Jeritza was the supreme interpreter of Marietta: a singing sex bomb, by all contemporary accounts. And a wild stage animal. (She was in Korngold’s 2nd version of Eine Nacht in Venedig at Staatsoper Wien in 1929. She also sold her villa to Emmerich Kalman when his family expanded, and she was later a friend of the Kalmans in their New York exile. Her operetta ties were close.)

Miss Jakubiac is a very attractive stage presence, too, in Babylon Berlin type costumes by Petra Reinhardt. But she’s no wild stage animal. And the many sudden emotional outbursts of Marietta seemed tricky for her; on the other hand she was glorious in the other-worldly moments of Marie, the dead wife coming back from the grave. (With stunning video work by Will Duke.)

Aleš Brisein as Paul in “Die tote Stadt” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

As a staging, we see a typical Carson single-space-for-the-entire-evening, created by Michael Levine: a large stylish bed room whose walls and ceiling can move and turn into a street and contain the massive religious procession with lit-up statues of Virgin Maria carried around by the choristers.

Here, as elsewhere, conductor Ainārs Rubiķis contained the orchestral forces as best he could. He offered a ‘slim’ reading of Die tote Stadt, which was a blessing. (Because no one can cope with three hours of non-stop fortissimo.) His tempi were often extremely slow, e.g. for Marietta’s Lied where he ‘lost’ the soprano at times. Then again, he dashed forwards with a speed that was unexpected. Rubiķis obviously wanted his Korngold to sound different, with sharp drum sections thrown in for cutting effect. I did like the almost trance quality of the slow moments, even if they brought the show to a stand-still at times.

“Die tote Stadt” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

The premiere was transmitted live on OperaVision. You can marvel yourself at the beautiful sets and costumes there. And ask how much operetta is contained in Die tote Stadt. The nostalgia that the Korngold score evokes is a nostalgia that also informed his Johann Strauss work directly afterwards. Whether Pierrot’s “Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen” is a jazzy ballad that you ideally hear in a smoke-filled whiskey bar (as Rubiķis says in an interview in the program booklet) is something worth considering, too. What struck me most was that with all the current fascination for Weimar Republic life and culture it seems difficult to actually get into the ‘style’ of the time for many singers, they shy away from the desperation, exaltation, and almost grotesque use of kitsch back then. Without them, though, the ‘true’ Weimar feeling only partially works. And it’s exactly these elements that make Weimar so current and relateable for us today.

All in all, it’s great hearing Korngold’s Die tote Stadt in direct combination with the many other typical Komische Oper titles on offer right now – works that had been branded by the Nazis as ‘degenerate’ and banned, but that were highly successful and influential before 1933. It’s a context that does Korngold good.

Advertisment for “Babylon Berlin”, which is also shown on Netflix.

The Carsen production is visually close to typical Komische Oper style – so we might have a repertoire production of this classic for the next few years. Considering that the entire world seems to have rediscovered Die tote Stadt lately (with a production at La Scala coming up soon) it’s good to know that the opera is back where it belongs: modern day Berlin Babylon. If anything, Komische Oper has proven under the artistic direction of Barrie Kosky that it can attract modern Berlin audiences like few other opera houses with its Babylonian approach to opera and operetta.

Watch the entire performance on OperaVision here. For further details, performance dates and tickets, click here.

All images by Iko Freese are from www.drama-berlin.de (Agentur für Theaterfotos).