Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

17 June, 2014

There’s a lot of talk, again, these days about „Operetta Made In Berlin”—how it differs from other German language types of operetta, most notably that from Vienna, how it was more adventurous and international than its Austrian counterpart, and how the jazz influence more readily embraced makes it more ‘modern’ and ‘interesting’ today.

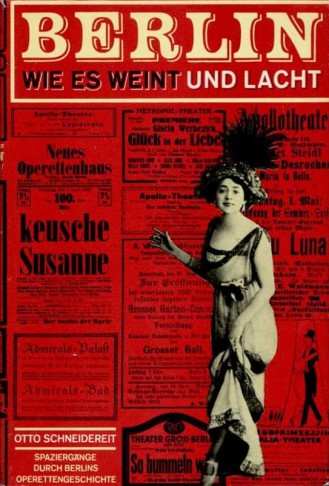

The cover of “Berlin, wie es weint und lacht” (1968).

Of course, the operetta scene in Berlin did not begin with the Roaring Twenties, and it did not end in 1933 when the Nazis took over and changed the genre, radically. Also, the vaudeville origins of operetta in the German capital in the 19th century, the “Possen mit Musik” of the early period and those apparently ‘homey’ shows by Paul Lincke, Walter Kollo, Jean Gilbert and Victor Hollaender were not as old-fashioned as many later experts have tried to make us believe.

The best book chronicling operetta history in Berlin, from the early 1800s onwards, including Nazi times and the post-WW2 years and (!) including a chapter on the different ways operetta went in East and West Germany after 1945 is Otto Schneidereit’s Berlin, wie es weint und lacht.

The subtitle sums it up neatly: “Spaziergänge durch Berlins Operettengeschichte.” It was first published in 1968 by VEB Lied der Zeit.

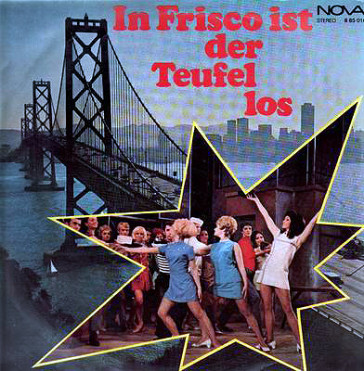

Schneidereit was East Germany’s foremost operetta expert, working at the Metropol Theater in Berlin. Not only did he publish extensively on the genre (the list of his books is very long indeed), he also wrote the libretti for various famous DDR operettas, among other Bolero (music: Eberhard Schmidt) and Guido Masanetz’ In Frisco ist der Teufel los. (The latter being the most successful operetta of them all in Socialist Germany.)

Otto Schneidereit in 1956.

His books are easily available in second hand book stores and online outlets. That none of them have been reprinted after the reunification of Germany is somewhat surprising, not even his Fritzi Massary and Richard Tauber biographies. Especially if you consider how much better all of his operetta guides are – including their “socialist” comments on individual works – to, let’s say, Heinz Wagner’s Das große Operettenbuch: 120 Komponisten und 430 Werke. (With an intro by operetta champion René Kollo that is so banal it makes me weep.)

If you are interested in Berlin and Berlin’s operetta history, then Berlin, wie es weint und lacht remains the classic you need to get.

It is richly illustrated and clearly structured history book. Why no one has translated it into English is anyone’s guess. It would most certainly deserve wider international recognition. As an English langue edition, it could proudly stand up next to Richard Traubner’s Operetta book (which is a problematic publication when it comes to the German language titles dealt with, since the author obviously doesn’t speak German and does not know the German cultural scene well), it could also stand up next to Kurt Gänzl’s books, as a welcome addition, giving more details topics Gänzl just brushes in passing.

The LP cover of Schneidereit’s greatest stage success, “In FRisco ist der Teufel los”.

And, any operetta book that puts Fritzi Massary and Jean Gilbert’s Berlin hit Die keusche Susanne (and Paul Lincke’s Frau Luna) on the cover, get’s an extra cheer from us here at ORCA. If you don’t already own this book, buy it immediately. And enjoy the rich history presented there. It will make you re-appreciate the pre-WW1 era of Berlin’s operetta scene, the big revues at the Metropol Theater and the international flair these shows had—something that Barrie Kosky, intendant of the Komische Oper Berlin (the original Metropol building) claims to take as his guiding light and something Kosky tries to get back to, in spirit at least.