David Slattery-Christy

Heritage Theatre / www.christyplays.co.uk

28 September, 2020

Elsie Hodder was born in a rather squalid theatrical lodging house in Leeds on 8 April, 1886. Her mother was a theatre dresser come dressmaker and her father was said to be either Bert Hodder, a theatre fly man and alcoholic, or Billy Cotton, the manager of the Prince of Wales Theatre and music-hall in Salford near Manchester. Cotton was related also to the actress Ada Reeve.

Lily Elsie in one of many “star portraits” from the 1920s. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

As she grew older there were also rumours she was an illegitimate child of the Guinness family dynasty, although that legend was never proved or verified in any way and seemed to be propagated for the glamour it suggested rather than any basis in truth. Hardly an auspicious beginning for a child who would become the most photographed young woman of the Edwardian era, and a theatre star like no other, who was revered by the public as their darling Lily Elsie.

As a child performer and singer she was billed as ‘Little Elsie’ and her mother soon realised, after Billy Cotton persuaded her to allow the child to go on stage, that her daughter and the talents she possessed were a potential meal ticket out of poverty. Elsie recalled “I sang ballads. Some friends were flattering enough to call me the infant Patti.” That was praise indeed because at the time Adeline Patti was a world famous of opera soprano. Tragedy would strike and by the late 1890s her father Billy Cotton died suddenly of a heart attack and left both Elsie and her mother bereft and alone.

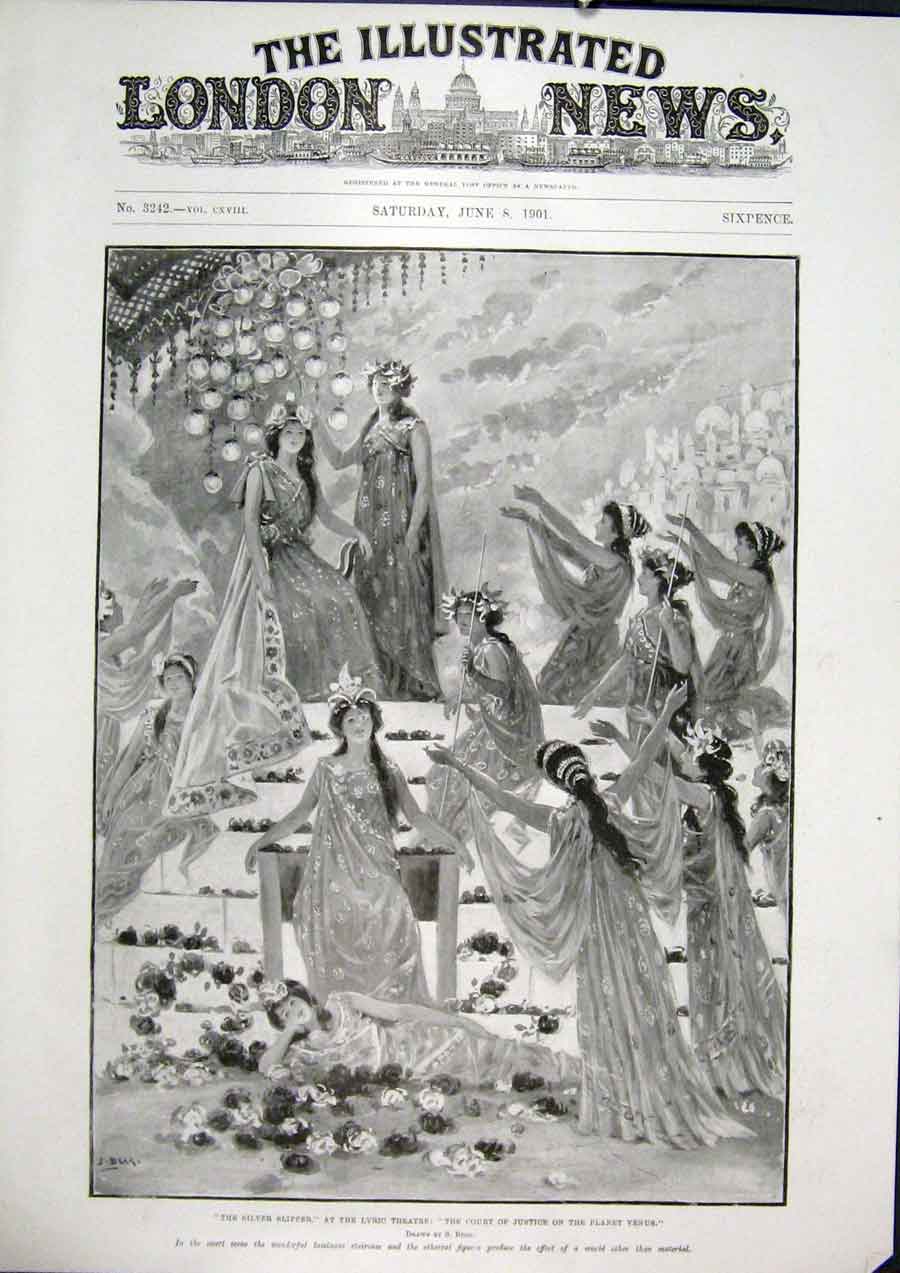

“The Illustrated London News” reporting in 1901 on the production of “The Silver Slipper” set on the planet Venus – an “Adamless Eden.” (Photo: London Illustrated News)

After moving to London and taking whatever jobs they could to survive, Elsie was blossoming into a beautiful young girl. Realising that ‘Little Elsie’ seemed inappropriate now she was older she decided to use the stage name of Lily Elsie. Her first success came when she was contracted to be photographed for the popular picture postcards of the time. She soon became a favourite of collectors. Her first successful audition was as a chorus girl in the revue The Silver Slipper at London’s Lyric Theatre on Shaftsbury Avenue in 1901. The Producer was George Edwardes who had made a great success of the Gaiety Theatre, Daly’s Theatre and the Savoy Theatre with his glamorous musicals in London’s West End. It was in this production that Lily Elsie first caught his eye and he decided to groom her as a future star. She was then cast in varying roles in A Chinese Honeymoon (1903), Lady Madcap (1904), The Little Michus (1905), See See (1906) under Edwardes’ management.

The “Little Michus Waltz” from Andre Messager’s operetta hit. (Photo: Chappell & Co.)

Elise and Edwardes formed a strong bond of friendship and he took her to Germany in 1907 to see Marie Ottmann play Hanna Glawari opposite Gustav Matzner as Danilo in the Berlin production of Die lustige Witwe by Franz Lehar, an almost 1:1 replica of the 1905 Viennese original which starred Mizzi Günther and Louis Treumann. (The Berlin production is the first in operetta history to be recorded completely, released on CD for the first time ever by Truesound Transfers, allowing us to actually hear the show in full, the Viennese stars made recordings of various highlights in 1906.)

Gustav Matzner as Danilo and Marie Ottmann as Hanna in the original Berlin production, 1907. (Photo: Christian Zwarg Archive)

At the end of the performance over dinner Edwardes told Elsie he wanted her to play the role of the Merry Widow in the London production. Elsie’s first reaction was to laugh as she could not imagine herself portraying the widow vocally as powerfully as she had seen Marie Ottmann do it that night. Edwardes would not accept no from her and was determined she would do it. He thought Ottmann (as well as Günther) was too old, rotund and with a loud soprano voice he felt the London audiences would not accept in the role. He told her that his librettist Basil Hood (1864-1917) would rewrite the book of the operetta, originally written by Victor Leon and Leo Stein, so it would suit a London audience and that the widow would be called Sonia and not Hanna as in the original.

The “Merry Widow” waltz turned into the “Sonia Valse” by Pedro de Zulueta, showing Lily Elsie as Sonia. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

On returning to London Edwardes engaged a special singing teacher for Elsie to teach her the music and songs from The Merry Widow.

Cecily Webster who worked in the chorus with Elsie remembered: “I first met her in the dressing room at Daly’s Theatre which she shared with a friend who had a small singing part in the Little Michus – she was hardly known except for the picture postcard craze. She subsequently left Daly’s to play the lead in See See, a charming little Chinese Musical Comedy, with excellent music. It must have been then that George Edwardes realised her possibilities. During that time, I had been accepted for the chorus at Daly’s, having gone to one of the weekly auditions just for fun – I remember very well, while the very small chorus of us were being taught the music on the empty stage, that Elsie came in quietly to listen (she did everything quietly). I asked her why she was there and she told me that Edwardes had asked her to read the part of The Merry Widow. Edwardes did not want a big star for the part for he was hard up after the comparative failure of his previous show. It is one of the mysteries of Edwardes’ judgment that he underestimated (or so we thought) the beauty of the little opera, still more underestimated the beauty of the widow herself. He did everything possible for her, he sent her to a voice trainer who did a lot of work for him, I forget her name – she took Elsie in hand, did marvels with her sweet voice – she drilled her in every line of music, and as we all know she produced a miracle.”

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in ‘The Merry Widow’, 1907. Elsie and Coyne are playing the parts of ‘Sonia’ and ‘Prince Danilo’ respectively.

The Merry Widow opened at Daly’s Theatre in June of 1907. Lily Elsie’s youth and ethereal beauty and wonderful singing voice catapulted her to stardom overnight and the Merry Widow became a huge hit in London’s West End. Lucille’s costumes also created new fashions that were emulated everywhere including the huge hats she created for Elsie to wear in the operetta. These became known as The Merry Widow Hats.

Lily Elsie in the third Act of “The Merry Widow” in London, 1907. The “Merry Widow Hat” became a ubiquitous fashion in London. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Stardom did little to bolster Elsie’s confidence though and she remained elusive and suffered stage fright and nerves that incapacitated her to the point where people who had booked weeks ahead were critical when she was once again not appearing and her understudy was on. Edwardes remained loyal and protective of his new star and shielded her from the gossips and the criticisms as much a he could. This was the start of Elsie’s depressions and paranoias that would get worse as she grew older.

This success would be followed by other operettas for George Edwardes in London’s West End and included: A Waltz Dream (1908), The Dollar Princess (1909), The Quaker Girl (1911) and The Count of Luxembourg (1911).

Lily Elsie in a scene from “The Count of Luxembourg,” London 1911. (Photo: Randy Bryan Bigham Collection / Wikipedia)

Ian Bullough, an about town aristocrat, had wooed Elsie and she finally agreed to marry him in 1911. She announced her retirement from the stage and much to Edwardes’ disappointment refused to be persuaded to return.

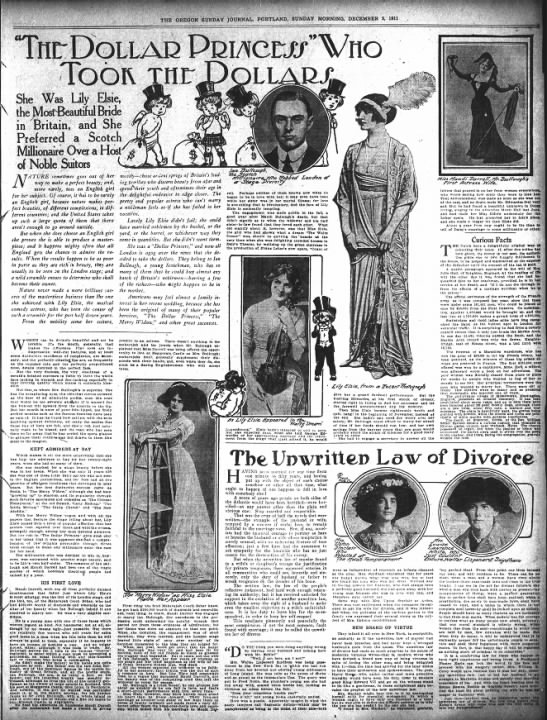

A 1911 newspaper reporting on “Scotch Millionair” Ian Bullough, “robbing” London of a “stage divinity.” (Photo: The Oregon Sunday Journal)

By 1915 her marriage was in trouble. Elsie began to suffer serious nervous disorders and found intimacy very difficult – this is not unusual in people who have mental health problems and depression. There was also a strain on the marriage as she was unable to have children.

Divorce at this time was unheard of for many and could seriously damage the reputations of those involved. As World War 1 was raging, her husband became involved in the war effort, and George Edwardes was also dead. So her father figure was no longer around to protect her.

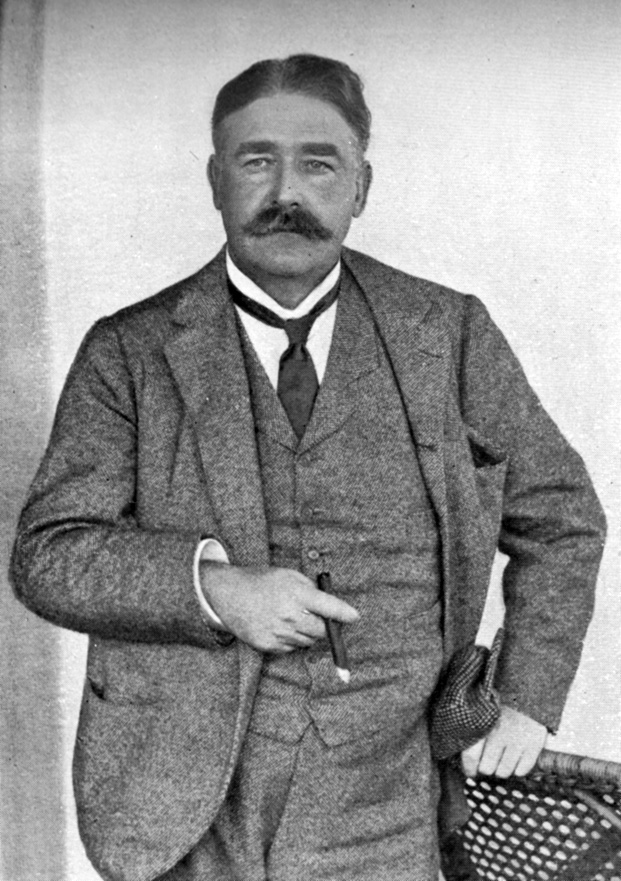

Photograph of George Edwardes by Ellis & Walery, from the 1914 edition of Cellier & Bridgeman’s “Gilbert and Sullivan and Their Operas.”

The Edwardian ideal had gone and the world moved on. She appeared in the musical comedy Mavourneen (1915) and then another Pamela (1917) and The Blue Train (1927) with little success compared to her Merry Widow triumph, although audiences still revered and adored her. She had no pressure to work as her husband came from a wealthy family who owned cotton mills in the north of England, so she was independently wealthy as a result of her marriage.

Lily Elsie with Ivor Novello who she appeared with in 1928 in “The Truth Game .” (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

Her last stage appearance was with Ivor Novello in his play, written specifically for his to star in with Elsie, titled The Truth Game (1928) at the Globe Theatre (now Gielgud) and then at Daly’s Theatre (1929) where she would play her last performance as a star in the same theatre where she gave her first.

A colleague, Rebecca West, from her Daly’s days, remembered Elsie for her beauty after an article about her by Cecil Beaton appeared in the Daily Telegraph: “Thank you so much for waking the beauty of Lily Elsie and her lovely pensive amiability, how beautiful Lily Elsie and Ivor Novello were together (in The Truth Game) like two fawns in a Sultan’s Garden, they should have eaten flowers.”

The glamorous Lily Elsie in her “court dress” 1912: this is how she was presented to the King and Queen after he marriage. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

By the early 1930s she had finally agreed to divorce Sir Ian Bullough although she still loved him dearly – and he, her. She respected that he wanted to have children and an heir, so she reluctantly consented. He gave her a very generous settlement as part of the divorce including the flat at Stanhope Place, Hyde Park. She was shattered when in the mid-1930s he died suddenly of a heart attack and her own mental health, always fragile since she was in her twenties, deteriorated rapidly from this time.

She received regular electro shock treatment therapy and even underwent a lobotomy in an effort to cure herself, but to no avail. She retreated from public life and appeared seldom at any events or functions but when she did she was adored by the public.

One of the most famous electro shock therapy scenes can be seen in the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; more recently director Ryan Murphy showed the full shock value of such a therapy in American Horror Story: Asylum where electro shock treatment is used to “cure” female homosexuality.

This side of her life, and the treatments she received, was never reported or made public so her fans never knew her struggles with what we would now recognise as bi-polar disorder that the lobotomy made much worse. This kind of revelation, at that time, could have damaged her reputation and it was something that was hidden (very English!) and not talked about openly.

The newspaper “The Sphere” reporting on Lily Elsie’s 64th birthday and showing her in older age. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

She lived in a convent at Dollis Hill, London, for the last few years of her life. She distanced herself from her niece, Elise Hodder, and refused to see anyone but intimate friends like Cecil Beaton who often took her out for rides in his car. Another long standing friend, Mrs Winifred Graham Hodgson, who had stood by her through her treatments for her bi-polar condition, named her daughter Sonia after Elsie’s Merry Widow character. Sonia Berry, as she became known after her marriage, would help me when I was writing my biography on Elsie, she became my living link to her.

Lily Elsie died on 16 December, 1961, aged 75. She left almost her entire estate to her friend Winifred Graham Hodgson.

As she had no children or immediate family, apart from a niece called Elise Hodder, who she cut out of her will, her life and achievements slowly slipped beneath the waves of time and she was in danger of being forgotten as those who had adored her and followed her career died away. Luckily a campaign, initiated by me and Sonia Berry, was launched several years ago to have a blue plaque placed on her former London home at Stanhope Place, Hyde Park. This finally came to fruition in 2019.

Rosemary Ashe unveiling the Lily Elsie plaque in London, 2019. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

In August of that year I invited West End soprano Rosemary Ashe to unveil her plaque and was joined by Roy Hudd OBE (President of the British Music Hall Society now sadly deceased) along with the daughter and granddaughter of Sonia Berry gathered to honour the memory of Lily Elsie and her achievements as the star of original London production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow at Daly’s Theatre.

A blue Lily Elsie plaque on her former London home at Stanhope Place, Hyde Park. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

I will leave the final words to historian W. McQueen-Pope who said: “To that gracious lady ‘The Merry Widow’ who entranced us, the ‘Sonia’ who captured our hearts and who waltzes forever in our memories, Lily Elsie.”

Biographer David Slattery-Christy (l.) with Rosemary Ashe and Roy Hudd, 2019. (Photo: David Slattery-Christy Archive)

Edwardian Beauty. Lily Elsie & The Merry Widow by David Slattery-Christy is available in paperback and audio book.

My maternal grandparents knew her and purchased her house in Redmarley d’Abitot in Gloucestershire in the early 1930s. Her beautiful handmade curtains remain in my family although sadly not with me.