Roland H. Dippel

Operetta Research Center

20 September, 2020

Is this the start of something like “reparation” after an endless period of neglect? On 18 September 2020 Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten premiered at Westbad, the venue where the Musikalische Komödie Leipzig is currently performing. DDR operetta guru, Otto Schneidereit, once called this show by Gerhard Kneifel (1927-1992) a “Prussian farce.” After the first night in East Berlin’s Metropoltheater on 24 April, 1970, the show made its triumphant way to nearly every theater in the socialist part of Germany. As early as 12 December, 1970, it weas first produced at Musikalische Komödie, then one of the two main operetta houses of the DDR (the other being Staatsoperette Dresden).

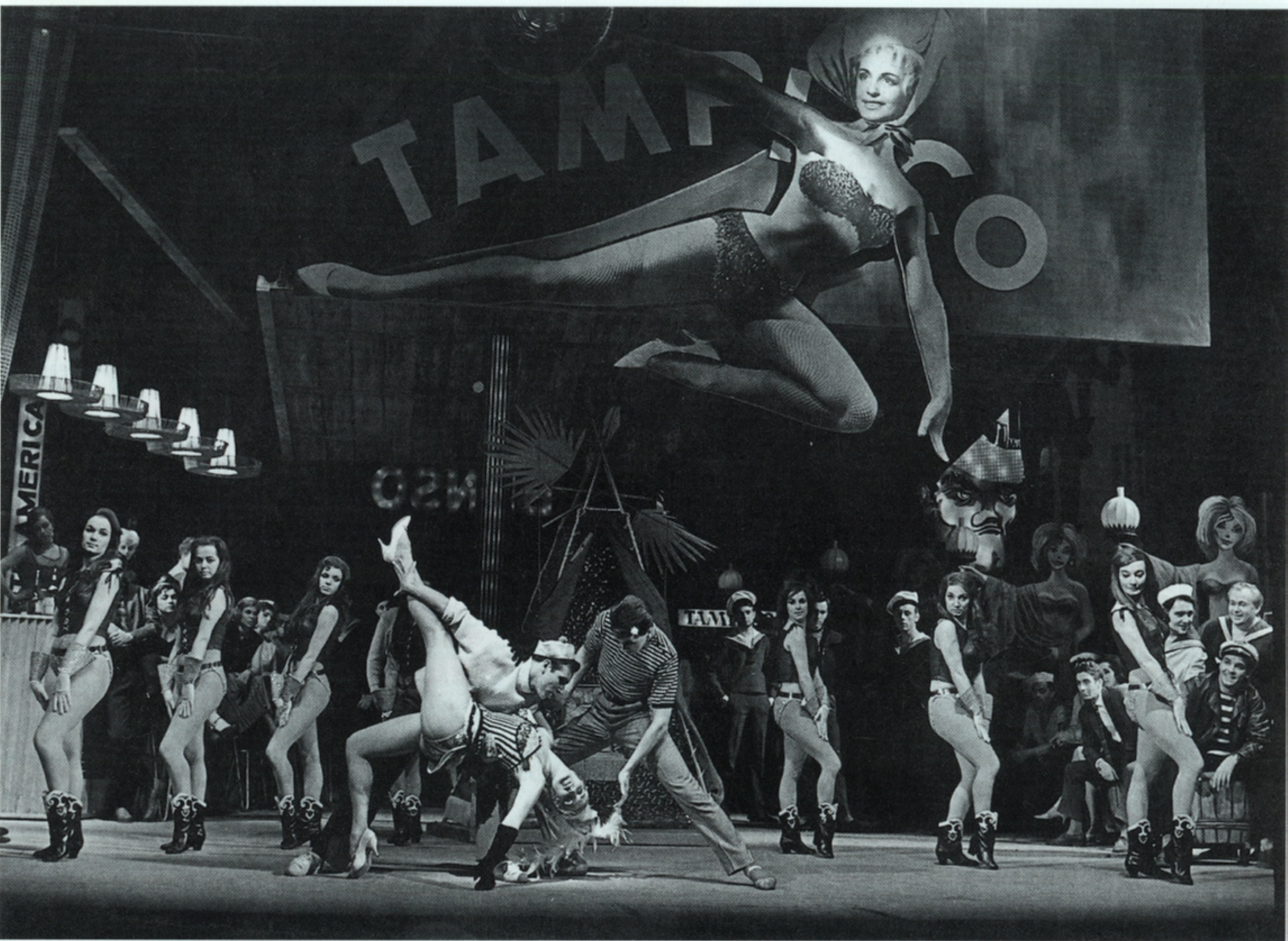

Scene from the 1970 world premiere production of “Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten” at Metropol Theater Berlin. (Photo: From the catalogue “Welt der Operette” / Österreichisches Theatermuseum / Brandstätter Verlag)

Fast forward to 2020, and this long ignored – if not forgotten – success makes a comeback at its former place of glory. It’s one of the few and only stage productions of a work from the category “Heiteres Musiktheater,” which is how ideologists in the former East labeled new musical entertainment works that tried to bridge the gap between musical and operetta. Ever since the wall came down in 1989 these works have been ignored, as if toxic, and left to rot away in archives. With the exception of titles by Guido Masanetz and Gerd Natschinski none of the once-famous “Heiteres Musiktheater” heroes (literally “cheerful music theater”) managed a post-DDR career. And now: Gerhard Kneifel’s “Prussian farce” was cheered, long and loud, by a new generation that attended the Westbad premiere.

And a memorable evening it was, in more ways than one. Shortly before rehearsals began, an interval was permitted, despite Corona regulations, making a full-length performance possible, instead of a reduced single act version. Inspired by a academic afternoon at MuKo in October 2019, musical director Stefan Klingele was eager to explore and test a piece from the DDR beyond the well-known top titles Mein Freund Bunbury (still in MuKo’s set storage), Messeschlager Gisela and In Frisco ist der Teufel los (performed as a semi-staged homage on Guido Masanetz’ 101st birthday in 2015).

A scene from “In Frisco ist der Teufel los,” 1962.

Choosing a work by Gerhard Kneifel was pretty obvious: Bretter, die die die Welt bedeuten premiered in Leipzig only eight months after the Berlin world premiere. Kneifel worked and died in Leipzig. He also assisted in getting the then young genre of a unique DDR “musical” off the ground with Die schwarze Perle at Theater Erfurt in 1962. His last stage work Aphrodite und der sexische Krieg (Aphrodite and the Sexual War) premiere at MuKo as late as 1986, one of the last musicals to be produced in the German Democratic Republic before its collapse; it was an important bridge to the era of reunification. With this anti-war piece Kneifel and Wolfgang Tilgner took up ideas from the GDR peace movement, and in the famous “opportunist song” they verbalized the grievances of the slowly falling apart state and its many discrepancies.

Originally, Bretter was to have been performed in April 2021 in the so called Venussaal of the renovated MuKo. But due to the permanent postponements caused by Corona, the production was moved to the slot that was originally reserved for Lehár’s Juxheirat as opener of the 2020/21 season. (For more information on Juxheirat and a recent production in Santa Barbara, click here.)

After the change of venue, the newly allotted space allowed for a larger cast, so the Venussaal “pocket format” was turned into a bigger event with a medium-sized orchestra, a large group of soloists and four dancers. On the other hand, the interludes were reduced by the company’s artistic director Cusch Jung. And finally there was something like real “Personenregie” – and real full blooded theater!

The text was edited and adapted by Daniel Hirschel with meticulous attention to detail. First and foremost there are the treasured quotations from the classic farce Der Raub der Sabinerinnen (TheAbduction of the Sabine Women) by the Schönthan brothers, on which this DDR musical is based. Mr. Hirschel took into account the degree of social criticism possible in the German Democratic Republic, which was utilized to the max by authors Helmut Bez and Jürgen Degenhardt. Together, they whipped the “Heiteres Musiktheater der DDR” from old fashioned operetta to contemporary musical. Hirschel enriched the text with discreet ingredients, which made it easier for modern audiences to understand the specific DDR type ‘Zwiedenk’ as another level of communication between stage and audience, a sort of reading between (“zwischen”) the lines and filling the gaps yourself with all the things that were impossible to say officially. 30 years after reunification many younger people are unaware of this specific element that was part of many DDR shows.

The brilliant opening night was entertaining, thoughtful, and more self-critical than self-referential – especially with regard to a specific socialist “aesthetic.” In the audience sat various MuKo protagonists of the past: Monika Geppert (retired director), Erwin Leister (retired chief director), Roland Seiffarth (retired chief conductor) and the family of the composer. But the cheers came mainly from unbiased spectators. After all, the time gap between the premiere of Bretter, die die die Welt bedeuten and today is as big as between Leo Fall’s Die geschiedene Frau (1918) and the sexual revolution of the Sixties.

On several levels this revival was also about the (non-)knowledge of the later-born, and about the latent social explosiveness behind the old-fashioned attitudes with which Kneifel, Bez and Degenhardt cunningly acted. For example, they shifted the time period of the story from 1884 to 1905, moving Bretter, die die die Welt bedeuten dangerously close to Heinrich Mann’s notorious Der Untertan, the DEFA film version of which was banned in West Germany for representing the “wrong” type of critical national history. It’s a classic, to this day.

Poster for the controversial movie “Der Untertan,” based on the Heinrich Mann novel.

Thus Bretter, die die die Welt bedeuten fits extraordinarily well with the MuKo focal points, from Prinzessin Nofretete to the musical epic Doctor Zhivago and Jean Gilbert’s Die Kinokönigin (The Queen of Cinema) due in December 2020: Gerhard Kneifel, Guido Masanetz and Gerd Natschinski are all unmistakable foster children of Nico Dostal and Fred Raymond, but also half-brothers and sisters of Broadway legends such as Cole Porter and Frederick Loewe.

The orchestra of the Musikalische Komödie celebrated such relationships, Schott publishing provided conductor Christoph Johannes Eichhorn with a copy of the hand-written score that is difficult to decipher, but still allowed for working with authentic material.

In the beginning, the soloists sit on the podium in a semicircle and awaken, as if from a long sleep. Cusch Jung’s narrator text soon recedes behind direct dialogue. The fear that this introduction might be meant as a creative new beginning after a negatively connoted DDR culture shock paralysis is not fulfilled.

Behind the two directors, the complementary figures of the upper middle class and the troop of roaming players frowned upon by them are positioned opposite each other. They all seek the other: the middle class citizens want the taste of freedom and adventure, the artists wish to settle down and live a secure life.

Milko Milev introduces himself with a fine pianissimo as “Herr Direktor” Striese. For Michael Raschle, who strokes the ladies’ knees with his eyes as Gollwitz, corporal punishment would be the absolute no-go. At the center of the sociologically correct constellation of figures is Andreas Rainer as Dr. Leo Neumeister, and he shows a very high affinity to the disciplinary methods that were common from 1933 onwards.

Also great are the others: Nora Lentner (the theater-loving older daughter Paula), the new member of the ensemble Vikrant Subraminian (Sterneck, the intellectual bon vivant with contact to political back rooms), Theresa Maria Romes (as the butcher’s daughter from Teltow, styled as the Italian countess), Angela Mehling (Mrs. Striese) and Anne-Kathrin Fischer (Mrs. Prof. Gollwitz) as the great mothers of their spheres, as well as Anna Evans (Dr. Neumeister). About all of them and Mirko Mahr’s stylistically authentic choreography one can only say: bravo! Also about Frank Schmutzler’s empty stage with heavy purple curtains and a Thespian cart!

What’s very obvious in the music is how the various historical lines cross, between East and West, pre-war and post-WW2, Europe and America. There are echoes of the last Nazi operettas (à la “Juliska aus Budapest“) but also of US-American hits like “On The Street Where You Live,” merged into something new, combined with Peter Kreuder and James Last, but also with Gerd Natschinski and Guido Masanetz, pointing towards Lotar Olias and Ralph Maria Siegel, Thomas Bürkholz and Birger Heymann.

Various famous operettas from Eastern Germany, as presented on an LP cover in the GDR.

The era of operettas and musicals between Feuerwerk (1950) and Linie 1 (1986) seemed completely forgotten by audiences and academics alike, ever since Wolfgang Jansen’ efforts with his “Gesellschaft für Unterhaltende Bühnenkunst” (active until 2000) fell dormant. To now fill this void again with a new production and stimulate new interest one cannot thank MuKo and musical director Stefan Klingele enough. It’s pioneer work!

One can only hope that there will be a CD/DVD made from this new production. Or at the very least a radio broadcast. (MDR, are you listening?)

For further details and future performance dates, click here.