Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

17 December, 2019

It was about bloody time, you might say, that someone published a new English language reference book on the history of operetta. After all, Richard Traubner’s Operetta: A Theatrical History is from as far back as 1983 and even in its 2003 update still claimed that operetta was “flowing champagne, ceaseless waltzing, risqué couplets, Graustarkian uniforms and glittering ballgowns, romancing and dancing,” not to mention “gaiety and lightheartness, sentiment and Schmalz.” German language scholars from 2005 onwards have proven that there is more to the genre than that. A darker and more political side that is worth exploring. And now, finally, a collection of essays published by Cambridge University Press makes some of these new debates available to an English speaking audience, in an attractively priced paperback edition clearly intended for a broader market.

The cover of “The Cambridge Companion to Operetta.” (Photo: Cambridge University Press)

So here is the 370 page Cambridge Companion to Operetta, edited by Anastasia Belina and Derek Scott. In their intro they say: “This Companion does not pretend to be all-embracing in its coverage of operetta. The editors were keen to place an emphasis on the production and reception of operetta in different countries and to examine its travels as an important form of cultural transfer. That said, the coverage is not all inclusive […]. It is important, however, to be aware that specific national traditions rarely occupy centre stage in operetta, and there is much that is cosmopolitan in its music and in its networks of trans-cultural exchange, which reached around the world. For instance, a variety of Australian touring companies (often sharing members) visited New Zealand, India, Hong Kong, Jakarta, Yangon, Singapore and Shanghai in the 1870s. In July 1879, Howard Vernon’s Royal English Opera Company gave performances of Offenbach’s The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein and Lecocq’s The Daughter of Madame Angot at the Gaiety Theatre, Yokohama, Japan, and excerpts of the former were interpolated into a westernized kabuki play at the Shintomiza theatre in Tokyo.”

Such an international scope also characterized Laurence Senelick’s recent Offenbach book. (To read an interview with Mr. Senelick about it, click here.) And a similar international perspective is very much evident here, too, with articles on operetta histories from Paris/France, Vienna/Austria, London, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Spain, the United States, Russia and the USSR, Nordic Countries, Greece, Italy, Poland, Berlin, and (covered via an interview with Barrie Kosky) in Australia.

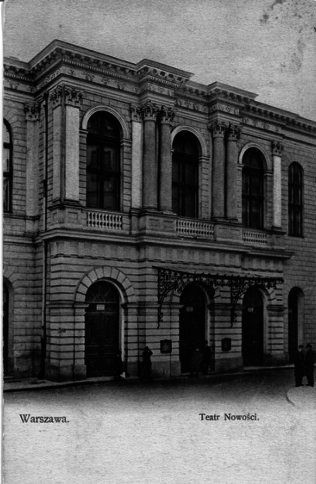

The Nowosci Theater in Warsaw. (Photo: Cambridge University Press)

That’s a lot of geography to deal with, and you might wonder why e.g. South America isn’t given its own chapter. But let’s not quarrel about that.

The essays by 18 authors are all covering fascinating material. What’s particularly grand is that Matthias Kauffmann gets to present a brief analysis of operettas from Nazi times, for everyone who hasn’t been able to read his monumental German language study on the topic.

Matthias Kauffmann’s “Operette im ‘Dritten Reich’.” (von Bockel Verlag)

Whether you find the various regional histories worthwhile is for you to decide, but it’s good to have them all next to each another. And it’s certainly illuminating what Anastasia Belina has to say about “Operetta in Russia and the USSR.” (Strangely, the operetta history in East Germany after World War 2 is not dealt with, neither is that in Western Germany in the 1950s, for that matter. It seems the respective works don’t yet deserve a critical English analysis, or so one could be made to believe here.)

There are some cheeky essays such as Bruno Bower’s “London and Gilbert & Sullivan” which starts by stating that the 2009 Cambridge Guide to G&S absolutely refused to call their works “operettas,” yet here they are in an Operetta Companion.

There are also less cheeky and somewhat less inspired essays like Lisa Feurzeig’s “Viennese Golden-Age Operetta” which – with its emphasis on “Volkstheater” – paints a picture of 19th century operetta in Vienna as “a people’s theater” that Marion Linhardt has proven wrong long ago. (Linhardt’s ground breaking Residenzstadt und Metropole is not even mentioned by Feurzeig. And maybe it is something particularly beloved by Americans to think of those Austrian works as some sort of harmless Disneyland, even if all historic evidence points in a different direction.)

Gold and Silver Operetta

The one thing that really irritated me about the volume, on a fundamental level, is the use of the terms “golden” and “silver” operetta from the start, without any explanation where this terminology comes from and what it stands for ideologically. If you take operetta histories like Otto Keller’s Die Operette in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklungfrom the 1920s this terminology is absent. Also, in operetta literature from Nazi times you won’t find it, instead they talk of “degenerate” or “Jewish” operetta as opposed to “Aryan” operettas. It so happens that the Nazi ideal of an “Aryan” operetta was that of Johann Strauss and his 19th century colleagues (Suppé, Millöcker, Ziehrer etc.) while they branded most 20th century operettas, certainly the jazz infused ones from Weimar times, as inferior.

When after WW2 such terminology seemed inappropriate, some clever Austrian authors called Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Otte used the gold and silver terminology in their 1947 book Die Wiener Operette and continued the old Nazi evaluation, only calling it differently. You might say it’s a simple little Nazi trick, for those still thinking along the old lines, even if they had to adapt to a new political system outwardly. (Hadamowsky and Otte are also strong defenders of operetta as “Volkstheater,” needless to say.)

Franz Hadamowsky and Heinz Otte, “Die Wiener Operette. Ihre Theater- und Wirkungsgeschichte,” 1947.

To find the terminology re-used here, without any critical discussion, is somewhat frightful. Especially because it suggests, again, that “golden” operettas from the 19th century are in some way worth more that “silver era” works, which is nonsense, and which is luckily never the aim to prove of any author in this book. But especially since it’s not the aim of the book to look down on the 20th century works it’s more than just a little unfortunate that this god-awful gold-and-silver-division has been applied. (It’s almost as awful as the “Volkstheater” claim, used, as it is here, for works that are not originally intended as “Volkstheater,” and not combined with a discussion of how operetta became “Volkstheater” – and what that meant once the Nazis defined the entire genre as such.)

The composer Sigmund Romberg, in 1949.

But let’s not get too hooked on this. And instead celebrate the book for what it is: a great overview of many new trends in scholarship. It even includes film operetta. And if Victor Herbert, Reginald de Koven, Jerome Kern, Rudolf Friml and Sigmund Romberg are not covered as extensively as they might be – in the context of Broadway operettas – then the editors tell us in their intro that this is because these composers were already covered in The Cambridge Companion to the Musical.

The new book is attractively packaged and priced. It’s a little strange that there are hardly any photos included to document the rich visual history of operetta and to show how the genre’s “look” changed over the decades and from region to region. What is refreshing is that modern day performances are referenced again and again, particularly the operetta revival kicked off by Barrie Kosky at Komische Oper Berlin. So it’s only befitting that he gets the last word in the book in an interview with Ulrich Lenz.

A scene from the original production of “The Beastly Bombing.” (Photo: Kim Gottlieb Walker)

All in all, this is a perfect Christmas present. And a treasure trove that invites you to discover many new aspects. My personal favorite aspect of the book is that in their introduction Anastasia Belina and Derek Scott discuss a modern-day example of a perfect operetta: Julien Nitzberg and Roger Neill’s The Beastly Bombing: A Terrible Tale of Terrorists Tamed by the Tangles of True Love which premiered in Los Angeles in 2006 before coming to Amsterdam in 2009.

To find this glorious show included here, after I myself have included it in the book Glitter and be Gay in 2007 and in the catalogue and exhibition Welt der Operette in 2011/12 (all in German) is an immense pleasure. Hopefully, this will stir the interest of more people to check out what today’s operetta can sound like – and what great potential the art form still has, when used with genius. (You can download audio files of all Beastly Bombing songs for free here.)

For an interview with Derek Scott on new aspects of operetta research, click here.